Katanga Masked Weaver (Upemba)

Ploceus katangae upembaeFAMILY

Weavers and Allies (Ploceidae)

LAST DOCUMENTED

1949

(76 years)

REGION

Africa

IUCN STATUS

Not Evaluated

Background

Description

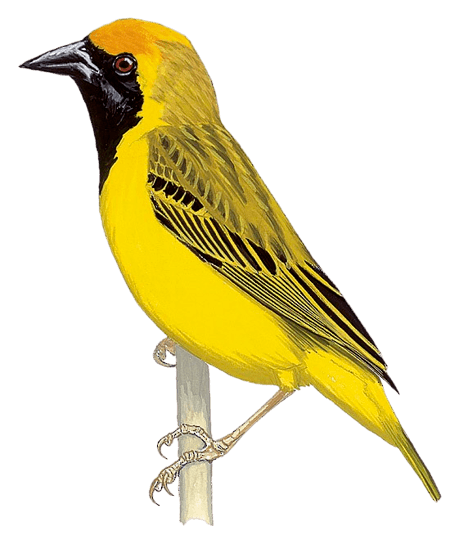

A relatively small, marsh-dwelling weaver

The males have the following characteristics:

Breeding male has a black forehead, lores, cheeks, chin, and throat that extends to the breast as a bib

Saffron yellow crown

Nape, mantle, back and rump are yellowish olive-green

Olive-green tail and wings

Wing-coverts are edged yellow

Breast, belly, flanks, thighs, and undertail-coverts are yellow

The females have the following traits:

Narrow yellow supercilium

Forehead, crown, cheeks, ear-coverts, nape, and back are olive-yellow

Streaking on mantle

Yellow rump

Chin to undertail-coverts are pale yellow

The Upemba Masked Weaver looks similar in appearance to the Katanga Masked Weaver (Ploceus katangae), the Southern Masked Weaver (Ploceus velatus), the Vitelline Masked Weaver (Ploceus vitellinus), the Lake Lufira Weaver (Ploceus ruweti), and the Tanganyika Masked Weaver (Ploceus reichardi)

This species differs from the Katanga Masked Weaver by being smaller, having a pale olive-green nape that merges with the mantle (instead of a yellow nape demarcated from an olive-green mantle by a vague narrow black line), a black mask that is less extensive, a larger bill, a greenish neck (not yellowish), less black on the head that creates a narrower forehead, a plain yellowish olive-green mantle, back of head, rump, and wing-coverts that do not have blackish streaks or edges, and the fact that females from this species are washed olive on the back instead of a warm brownish as seen on females from the Katanga Masked Weaver species

This species differs from the Southern Masked Weaver by having more saffron around the mask, less black on forehead, a darker green back, and a yellow-green rump that is seen in flight

This species differs from the Lake Lufira and Tanganyika masked weavers by having less saffron on the mask

The Upemba, Katanga, and Southern masked weavers are considered by many to be members of the Ploceus velatus complex

The Upemba and Katanga masked weavers are thought to be separated by an area of high, dry ground between Lake Mweru and Lake Upemba in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DR Congo)

Habitat

This bird’s range is known only extend to areas near the Lualaba River in southeast DR Congo

This species is known to inhabit wetlands and marshy areas like other species of masked weaver in Africa (Birds of the World)

This species is isolated from her closest relative, the Katanga Masked Weaver, and restricted to the wetlands of the Kamalondo depression

The Upemba Masked Weaver and her relatives are weavers that are specialists in marshes and wetland environments. As a result, they are highly vulnerable to habitat modification and disturbance (Cotterill, 2004)

The range of the Upemba Masked Weaver has been compared to other species of masked weaver that many think the bird is conspecific with or are her relatives

The Katanga Masked Weaver inhabits swamps and lakeside marshes within the Luapula-Chambeshi and Luongo-Kalungwishi drainage systems as well as sites such as Kafubu, Kimilolo, and Sumbu near Lake Tanganyika with its range encompassing south-central Africa and a patchy distribution in southeast DR Congo and northeast Zambia

The Southern Masked Weaver is one of the most widespread of the African masked weavers with a range that is further south outside the DR Congo to include western and southeast Angola, western, southern, and eastern Zambia, Malawi, northwest Mozambique south to the coast of South Africa, Botswana, São Tomé with some populations seen outside the African continent in faraway places such as the Leeward Antilles, Israel, and even Germany

The Vitelline Masked Weaver has a large range like her relative, the Southern Masked Weaver, that extends from southwest Mauritania, Senegal, Gambia, Guinea-Bissau, southern Mali, Burkina Faso, Ghana east to southern Chad, northern Central African Republic, southern and eastern Sudan, South Sudan, northeast DR Congo, central and southern Ethiopia, northwest and southern Somalia, northwest Uganda, and north and central Kenya south to central Tanzania

The Lake Lufira Masked Weaver is known from the Lake Tshangalele (or Lake Lufira) basin, Kinsamba, Kiubo Falls (which are near the Lufira River in southeast DR Congo), the southern end of the Tanganyika Rift, as well as around Lake Rukwa and the Saisi River on the border with Tanzania (Louette and Hasson, 2009)

The Tanganyika Masked Weaver’s lives around Lake Tanganyika, Lake Rukwa, and the Ruaha National Park with its range encompassing western Tanzania and northeast Zambia (Birds of the World)

Other Information

While much is still unknown about the Upemba Masked Weaver’s behavior, her relatives are known to breed in swampy wetlands

A popular theory among ornithologists is one proposed by F.P.D Cotterill that explains why the Upemba Masked Weaver and her relatives are isolated from each other in an archipelago of wetlands and marshes across central and southern Africa. He argus that drainage evolution among prehistoric wetlands explains why they are isolated and probably distinct species. The ancestor of the Upemba, Katanga, Southern, Vitelline, Lake Lufira, and Tanganyika masked weavers inhabited the Palaeo-Lake Makgadikgadi wetland that was part of a trans-Katanga system connected to the Zambezi and Chambeshi rivers. When this wetland broke up, new wetland archipelagos were formed that isolated this ancient population of masked weavers. Over time, they became different species due to their isolation from one another (Cotterill, 2004).

As of 2023, Upemba Masked Weaver Ploceus upembae is considered a subspecies of Katanga Masked Weaver Ploceus katangae in both the HBW/BirdLife Taxonomic Checklist and eBird/Clements Checklist (see Taxonomy below). Upemba Masked Weaver was considered as distinct species by the HBW/BirdLife Taxonomic Checklist in 2022 (version 1 of the Lost Birds List) and so has been retained on the website despite its change in taxonomic status and been relabeled as Katanga Masked Weaver (Upemba).

The upembae subspecies of Katanga Masked Weaver remains lost and with more data perhaps could potentially be considered a distinct species again.

Found only in the southeastern Democratic Republic of Congo, the last documented records of this weaver were in 1949.

Conservation Status

When considered a species, Upemba Masked Weaver was classified as Data Deficient on the Red List. As a subspecies it is currently Not Evaluated.

Experts believe that the bird’s range does not go farther than the Lualaba River with an extent of occurrence of 16,100 km2 (Birds of the World).

The range of the Upemba Masked Weaver lies within the Upemba National Park. Upemba National Park was created in 1939 and extended in the 1970s to include wetlands and other areas along the Lualaba River, Kundelungu, and Upemba. It is filled with lakes, the most important of which being Lake Upemba. The Upemba Masked Weaver is one of only four endemic species known to exist in the park. The other three include her relative, the Lake Lufira Weaver at Kiubo and close to Lake Lufira (an artificial lake created by the Tshangalele dam), the Black-Lored Waxbill along the banks of the Lualaba River, and Lippen's Spotted Ground Thrush (123dok.net). Protection within this park is questionable due to the incessant armed conflict that is happening within the DR Congo that can disrupt park operations. Urgent surveys are needed to see the damage these conflicts have done to wetland and marshy areas within the park that are known to support Upemba Masked Weaver populations. The population of this species has never been quantified (Birds of the World).

Last Documented

The first specimen of the Upemba Masked Weaver was collected at Mabwe in 1947 in the DR Congo by R.K Verheyen. Verheyen described the bird as a subspecies of the Southern Masked Weaver with the designation Textor velatus upembae. He reported that the species could be found around the Mabwe camp (Verheyen, 1953).

Another specimen was found a year later by G.F de Witte on December 16, 1948. According to him, the bird’s range only extended to the area near the Lualaba River in southeast DR Congo.

Specimens of these species have been found in the following locations near the Lualaba River in Upemba National Park: Bukama, Mabwe, Kadia (all three in the Upemba marshes), the Kamalondo depression, Kiambi (4 specimens), Manono (1 specimen), Kafubu, Kimilolo, Sumbu, and Lake Tanganyika (Birds of the World).

Sight records of the Upemba Masked Weaver have been scarce since the 1940s with next to nothing being known about the bird’s behavior. This only deepens the controversy surrounding the species’ taxonomic status.

Challenges & Concerns

The greatest challenge the Upemba Masked Weaver must face is the high rate of habitat loss that is happening across her narrow range. This habitat loss is caused not only by agricultural expansion but also by the indirect and direct impacts continuous armed conflict has had on diverse ecosystems in the DR Congo. During a wartime situation, there are several ways an armed conflict can negatively affect wildlife. Animals can be accidentally killed by mines or shells. They can be hunted and overexploited to feed troops. If they are an endangered species, they can even be used by hostages or pawns to hamper government troops or gain international support. War can affect park institutions in a reserve where endangered and vulnerable species are protected. Rebels can occupy an area and chase park officials away. With park institutions absent, this not only opens the door for rebels and poachers but also refugees from neighboring regions affected by the conflict to come in and overexploit park resources and destroy natural environments (Gaynor et al., 2016). All of these factors either have happened or continue to happen on some level in the DR Congo ever since the country ceased to be a Belgian colony in the 1960s. The armed conflict that has ravaged the country does not show signs of ending anytime soon. While large mammals tend to be the center of attention for economic reasons such as poaching, birds can be the target of poaching and habitat loss as war forces many in the country to overexploit resources to survive.

The DR Congo has among the richest and diverse ecosystems in the world. Ironically, these areas are also among the most poorly studied and ravaged by habitat loss as a result of the incessant warfare that has plagued the country since independence. The Upemba Masked Weaver is one of 13 rare species that are either only known from the DR Congo or are mainly known from this region. Other than the Upemba Masked Weaver, the list includes the Itombwe Nightjar, Itombwe Owl, Chestnut Owlet, Grauer’s Cuckooshrike, Lendu Crombec, Kabobo Apalis, Prigogine’s Greenbul, Sassi’s Greenbul, Chapin’s Mountain Babbler, Prigogine’s Sunbird, Black-Lored Waxbill, and Yellow-Legged Weaver. It appears that more and more of their habitat is destroyed by agriculture and overexploitation and more and more of their members are captured or killed due to poaching and hunting with every passing year. If the armed conflict in the DR Congo does not cease, it is unsure how much longer these rare species can continue to cope with the direct and indirect impacts war has had on their survival.

Research Priorities

Conduct a DNA analysis of one or more of the known specimens of the Upemba Masked Weaver to see if this bird is a distinct species or a subspecies as many taxonomists claim

When possible, launch a new survey of areas near the Lualaba River in the Upemba National Park to see if any populations of Upemba Masked Weaver still live there and to what extent these areas have been negatively affected by encroachment and habitat loss

Ongoing Work

Ever since the Upemba Masked Weaver was first described, taxonomists and checklists have been at odds over whether this bird is a distinct species or a subspecies within a larger species complex. Much of this debate has centered around the relationship between the Upemba and Katanga masked weavers. The former was originally classified as Textor velatus upembae which implies that this bird was seen as a subspecies of the Southern Masked Weaver that lived further south outside the DR Congo (Birds of the World). Due to their close proximity to one another, many debated whether the Upemba Masked Weaver was a subspecies of the Katanga Masked Weaver. This did not mean that they saw this as a distinct species since those that disagreed with this categorization often described the Upemba Masked Weaver either as a subspecies of the Southern Masked Weaver or as conspecific with the Lake Lufira, Tanganyika, and Vitelline masked weavers (IUCN Red List). Only a few have proposed distinct species status for this weaver. One of them was Michel Louette during the 1980s (Louette and Hasson, 2009).

In 2017, Thilina N. de Silva et al. (2017) published a study that created a phylogenetic framework for the Ploceidae family. This study covered 2/3 of all recognized weaver species (77/116). The Southern and Vitelline masked weavers were included in their analysis. They questioned the long-standing monophyly of the velatus superspecies complex. According to them, these two weavers should be in the genus Malimbus instead of Ploceus. Even though their relatives the Katanga, Lake Lufira, and Tanganyika masked weavers were not included in their study, they suggested these species should also be in Malimbus due to the assumption that these species were closely related. The Upemba Masked Weaver was not even mentioned possibly due to the fact that de Silva et al., considered this species to be a subspecies of the Katanga Masked Weaver.

As of now the Upemba Masked Weaver is considered by several checklists as a subspecies of the Katanga Masked Weaver despite the fact that little to nothing is known about the bird and her habits. This species has been lumped together with a similar-looking species based on a BSC (Biological Species Concept) that historically has had a bias towards morphological traits and making species complexes even when the evidence for them is scant.

In a study he published in 2006, F.P.D Cotterill argues how lumping species together and entrenched taxonomies based on the BSC and morpho-species concepts weaken taxonomic scholarship and makes it harder to do reappraisals and reviews. Cotterill calls this phenomenon taxonomic lumping. Taxonomic lumping has a bias towards synonymy that hides the evolutionary lineages of distinct species. Oftentimes, species that are labelled as subspecies are often forgotten. This can affect how they are studied and protected as a result. The consequences become even more serious if the species in question is a specialist in a restricted range such as the Upemba Masked Weaver. In his research, Cotterill found that 12 endemic species were overlooked in Katanga alone due to taxonomic lumping. He states that, "I repeatedly found that their [lumped species] noteworthy status as distinct evolutionary species has been obscured by synonymy (on occasion deeply entrenched in the literature).....Taxonomic lumping has obscured appreciation of the importance of Katanga's avifauna in terms of its evolutionary history (pertinently, endemism) and conservation significance. Such a deficiency in the contemporary taxonomy of Afrotropical birds is disturbing. If this example of Katanga's birds is representative, then negative impacts on decisions in science and conservation appear to be serious." Cotterill further states that reappraisals become even more difficult for Afrotropical birds that have been lumped due to inaccessible taxonomic knowledge on birds from Africa, the fragmentation of sources, and incomplete citations found in the literature. He concludes that it is much better to call a species distinct instead of lumping it until sufficient evidence is found to the contrary.

To prevent taxonomic lumping in the future, alternative taxonomic practices should be considered so other species are not put in the same precarious position as the Upemba Masked Weaver. In a study published by J.A Tobias et al. in 2010, they propose a new system whereby phenotypic divergence and the degree of divergence between sympatric and parapatric congeners are used to establish thresholds within a scoring system based on the BSC. These thresholds would include categories such as morphology, acoustics, plumage, ecology and behavior, and geographical relationships. If one uses their system, a score of 7.0 is enough for a species to gain distinct species status.

In addition to the system proposed by Tobias et al., the issue of taxonomic lumping brings up the question: which species concept is best when determining who is a distinct species and who is not? The most widespread concept in use today is the BSC that is based on reproductive isolation. Two other concepts have risen to challenge the BSC. They are the Phylogenic Species Concept (PSC) based on diagnosability and the Monophyletic Species Concept (MSC) that is based on monophyly, DNA analysis, and more participation from actors outside the field of taxonomy. All three have their strengths and weaknesses. As stated by Cotterill, the BSC tends towards synonymy and lumping species together. It is also oftentimes unclear how well a species is isolated in a reproductive sense. Paraphyly makes it difficult to access the diagnosability of a species with the PSC. Monophyly can be hard to ascertain with the MSC. Lastly, hybridization is a topic that all three have a hard time measuring (Tobias et al., 2010). There is no clear answer to this question as taxonomists continue to debate the merits and flaws of each concept.

In the case of the Upemba Masked Weaver, the damage has already been done. This species faces the same challenges mentioned by Cotterill. The fact that this species has been lumped in a system that has a bias towards synonymy is compounded by the fact that little is known about the bird’s habitat and behavior. Without this data, it is unlikely checklists will consider changing the Upemba Masked Weaver’s taxonomic status absent of a thorough DNA analysis or the (re)discovery of populations within or outside Upemba National Park in the DR Congo. Until then, we will have to hope that the bird survives in a country where the rate of habitat loss rises with each passing year due to warfare and agricultural expansion.

Taxonomy

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Ploceidae

Genus: Ploceus

Species: Ploceus katangae upembae/Ploceus upembae

Upemba Masked Weaver is currently considered to be a subspecies of Katanga Masked Weaver Ploceus katangae. The weaver was split as a distinct species by del Hoyo and Collar in 2016 and considered a distinct species in the HBW/BirdLife Taxonomic Checklist until 2023 when it was again lumped with Katanga Masked Weaver in v8.1 of the HBW/BirdLife Taxonomic Checklist. As a result of it being considered a distinct species in 2022, the Upemba Masked Weaver was considered as lost bird in version 1 of the Lost Birds list.

In the eBird/Clements Checklist, Upemba Masked Weaver is also considered a subspecies and listed in the eBird database as Katanga Masked Weaver (Upemba). Likewsie, the IOC World Bird List v14.1 also considers Upemba Masked Weaver to be a subspecies of Katanga Masked Weaver.

Given how little is known about this bird, it does not seem impossible that a rediscovery and updated information on the weaver's vocalizations and morphology could once again change how it is treated taxonomically.

Page Editors

- Nick Ortiz

- John C. Mittermeier

Species News

- Nothing Yet.

Support The Search for Lost Birds

Donations from supporters like you make expeditions, science, and conservation possible. Help support the Search.