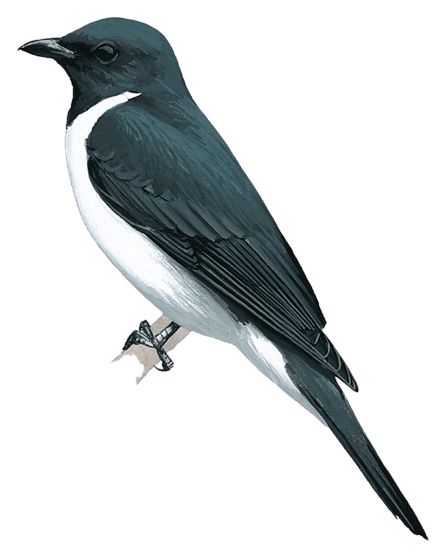

Grauer's Cuckooshrike

Ceblepyris graueriFAMILY

Cuckooshrikes (Campephagidae)

LAST DOCUMENTED

1997

(28 years)

REGION

Africa

IUCN STATUS

Least Concern

Background

Description

22 cm

Grey and white plumage overall

Fine, black bill

On the males, the head, upperparts, breast, and wings are a dark slate-grey that show up darker on the lores around the eye and from the chin to the breast

Upperparts, side of the neck, and breast have a slight greenish-blue gloss

Secondaries have glossy blue edges

Tertials, upperwing-coverts, alula, and primaries are black

The tail is black with a bluish sheen

Outer two feathers have white tips

Underparts, underwing-coverts, and axillaries are white

Lower flanks and thighs are medium grey

Iris is dark brown

Blackish-grey legs

The females are slightly paler overall with a medium grey head, neck, chin, and upper breast

Females also have darker lores and a pale buff on the undertail coverts

Juveniles are similar in appearance to the females but with a light grey forehead, spotted black lores, a grey throat with some blackish feathers, and beige undertail-coverts

Grauer’s Cuckooshrike differs from the White-Breasted Cuckooshrike (Coracina pectoralis) by being smaller in size and having a dark grey head, upperparts, and breast and from the Grey Cuckooshrike (Coracina caesius) by having white underparts

Habitat

This rare bird is known to live in a narrow range in the Albertine Rift Mountains in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

The only specimens were found in the highlands along the western side of the Albertine Rift from Djugu and Mongbwalu (west of Lake Albert) south to Lutunguru (west of Lake Edward), Mt. Kahuzi to Kitongo south to R. Elila west of Uvira

Prefers montane and transitional forests between 1,150-1,900 m

Inhabits a range that separates this species from other African cuckooshrikes, such as the Blue Cuckooshrike (Cyanograucalus azureus) and the Grey Cuckooshrike, that appear at elevations below 1,190 m

Behavior

Insectivore

Likes caterpillars

Forages mainly in the canopy, middle layers of the forest, and understorey

Other Information

Vocal behavior unknown with only one recording ever taken

Breeding behavior mostly unknown except that this species is believed to lay eggs between the months of January and June (Birds of the World)

Life span 4.33 years (IUCN Red List)

Conservation Status

This species has been classified as Least Concern by the IUCN with its last assessment in 2020. The large range of the Grauer’s Cuckooshrike prevents this species from being listed as Vulnerable according to the IUCN’s thresholds. What is interesting is that the IUCN assumes that the population size of this species is large enough to prevent it from being qualified as Vulnerable even when they themselves admit that its population density is unknown, in decline, and most likely small. Furthermore, many contend that Grauer’s Cuckooshrike is rare within its restricted range (IUCN Red List). Specimens of Grauer’s Cuckooshrike were collected between 1,140-1,900 m at an altitudinal range of 760 m (Bober et al., 2001).

To see a distribution map for Grauer’s Cuckooshrike, click here.

Last Documented

In the almost 120 years since the bird was described in 1908, all we have of this bird are 51 museum specimens, a recording made in 1997, and a slew of unconfirmed sightings.

From February 6-8, 1994, Tommy Pedersen, Marc Languy, and Laurent Esselen led an expedition to the Lendu Plateau to search for the Lendu Crombec (Sylvietta chapini) and Prigogine's Greenbul (Chlorocichla prioginei). By flying over the area, they were able to identify two main forest patches that had not been razed due to logging and encroachment from neighboring villages. These areas were Djugu close to the village of Nioka and another area close to the plateau’s edge east of Nioka. Each area was the size of around 10 football pitches. After searching both areas, they did not find any Lendu Crombecs but found 2 Prigogine’s Greenbuls. During their search they made an interesting note. They observed many Grauer's Cuckooshrikes in these two areas and even reported them as common in these areas (Pedersen, 1997). Thirty years later, it is unclear whether or not these forest patches still exist due to high rates of logging and encroachment in the region.

The last confirmed sighting of Grauer’s Cuckooshrike was by Dr. Thomas M. Butynski and Esteban E. Sarmiento in June 1997 when they were conducting a survey of the Alimbongo, Bingi, and Lutunguru regions in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Ironically, the main goal of the survey was to define gorilla populations west of Lake Edward. While they did not find any gorillas, they did find an elusive bird. While Butynski and Sarmiento did not see Grauer’s Cuckooshrike, they successfully made the first recording of the species call. They recorded the bird near the Lubélé River (Butynski and Sarmiento, 1997; Unpublished Report). This recording was included in Claude Chappuis' African Bird Sounds: Volume 1 (2000). The recording can be found on the CD that was created for the book. This CD is considered by many to be the most important collection of birds sounds in Africa.

Since the 1997 sighting, there have only been unconfirmed reports of Grauer’s Cuckooshrike in areas near the species’ recorded range. Some have seen the bird in the Rwenzori mountain range between the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Uganda. The Wildlife Conservation Society reported that Grauer’s Cuckooshrike was abundant in the Kisimba-Ikobo Community Reserve and the Kahuzi-Biega National Park (both in eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo) (Birds of the World). Despite their claims to the contrary, the fact that no photos or recordings were taken leads one to believe that Grauer’s Cuckooshrike is rarer and scarcer than they claim.

Challenges & Concerns

Grauer’s Cuckooshrike faces several threats to its narrow range between the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Uganda. The fact that this bird is also rarely seen and has a population size that is likely small only exacerbates her precarious status. Grauer’s Cuckooshrike resides in a region that is experiencing an unprecedented high rate of habitat loss as a result of slash-and-burn agriculture. Unregulated logging eliminates much of the understorey and canopies that the bird likes to use as a suitable habitat. The rising amount of political violence and instability in the region makes attempts to find Grauer’s Cuckooshrike very difficult for safety reasons (IUCN Red List). Poaching and bird trapping are also on the rise in the area where park officials feel beleaguered with patrolling thousands of acres of forest at a time where reserves and parks across Africa are coming under increasing stress from population growth.

This habitat loss is caused not only by agricultural expansion and unregulated logging but also by the indirect and direct impacts continuous armed conflict has had on diverse ecosystems in the DR Congo. During a wartime situation, there are several ways an armed conflict can negatively affect wildlife. Animals can be accidentally killed by mines or shells. They can be hunted and overexploited to feed troops. If they are an endangered species, they can even be used by hostages or pawns to hamper government troops or gain international support. War can affect park institutions in a reserve where endangered and vulnerable species are protected. Rebels can occupy an area and chase park officials away. With park institutions absent, this not only opens the door for rebels and poachers but also refugees from neighboring regions affected by the conflict to come in and overexploit park resources and destroy natural environments (Gaynor et al., 2016). All of these factors either have happened or continue to happen on some level in the DR Congo ever since the country ceased to be a Belgian colony in the 1960s. The armed conflict that has ravaged the country does not show signs of ending anytime soon. While large mammals tend to be the center of attention for economic reasons such as poaching, birds can be the target of poaching and habitat loss as war forces many in the country to overexploit resources to survive.

The DR Congo has among the richest and diverse ecosystems in the world. Ironically, these areas are also among the most poorly studied and ravaged by habitat loss as a result of the incessant warfare that has plagued the country since independence. Grauer’s Cuckooshrike is one of 13 rare species that are either only known from the DR Congo or are mainly known from this region. Other than Grauer’s Cuckooshrike, the list includes the Itombwe Nightjar, Itombwe Owl, Chestnut Owlet, Lendu Crombec, Kabobo Apalis, Prigogine’s Greenbul, Sassi’s Greenbul, Chapin’s Mountain Babbler, Prigogine’s Sunbird, Upemba Masked Weaver, Black-Lored Waxbill, and Yellow-Legged Weaver. It appears that more and more of their habitat is destroyed by agriculture and overexploitation and more and more of their members are captured or killed due to poaching and hunting with every passing year. If the armed conflict in the DR Congo does not cease, it is unsure how much longer these rare species can continue to cope with the direct and indirect impacts war has had on their survival.

Grauer’s Cuckooshrike also faces another threat that no one anticipated: excessive specimen collecting by museums of small, threatened bird populations within reserves. According to an eye-opening study by Dowsett-Lemaire et al. (2015), representatives from museums across the world (especially those in Africa and the West) engage in practices where they collect a disproportionate amount of birds in nature reserves despite the fact that many of these birds are threatened, have a limited range, and have small populations. There are accounts of people killing and collecting birds in the hundreds, often during the breeding season where their impact is the most disruptive to endemic bird populations. This is obviously a colonial legacy that these institutions can do without. While their study focused primarily on this phenomenon in Malawi, it is not unreasonable to assume that such a phenomenon might not be happening in the Democratic Republic of the Congo or in neighboring regions close to the Grauer’s Cuckooshrike’s known range.

The fact that a confirmed sighting of the bird has not been recorded in almost 30 years is also concerning. While the IUCN classifies this species as Least Concern, circumstances within the species range suggest that Grauer’s Cuckooshrike is vulnerable and under pressure from several threats that endanger its survival.

Taxonomy

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Campephagidae

Genus: Coracina/Ceblepyris

Species: Coracina graueri/Ceblepyris graueri

The scientific name for Grauer’s Cuckooshrike was updated in 2016. While some organizations have adopted the change, others continue to use the bird’s original name, Coracina graueri.

Page Editors

- Nick Ortiz

Species News

- Nothing Yet.

Support The Search for Lost Birds

Donations from supporters like you make expeditions, science, and conservation possible. Help support the Search.