Chestnut Owlet

Glaucidium castaneumFAMILY

Owls (Strigidae)

LAST DOCUMENTED

1968

(58 years)

REGION

Africa

IUCN STATUS

Least Concern

Background

There is a lot of taxonomic controversy surrounding the status of the Chestnut Owlet as a separate species for the simple reason that there is so little data on this bird. This is combined with the fact that the species looks so similar to the African Barred Owlet and her associated subspecies. Furthermore, this species range and characteristics have been confused over the years with other subspecies of African Barred Owlet (especially the Albertine Owlet). In order to differentiate the Chestnut Owlet, it is necessary to compare this species with the African Barred Owlet and related subspecies.

African Barred Owlet (Glaucidium capense)

17 cm in length

Greyish brown upperparts marked with fine buff bars

Narrow white eyebrow

Scapulars and greater wing-coverts have white outer webs with dark brown tips that create a white stripe across the shoulder and the folded wing

Brown chest that is finely barred with buff

Breast and flanks are white with brown spots

Underwing coverts, legs, and vent are white

Flight feathers and tail are brown and barred with a rufous color

Bill and cere are a dull, greenish-yellow

Eyes, legs, and feet are yellow

This owlet likes moist and dry woodland forests

Has a wide range that stretches across South and East Africa with some population that are restricted to parts of Central and West Africa

This range includes the Eastern Cape and southern Kwazulu-Natal in South Africa

This species is seen as main species of the Glaucidium taxon

Head and neck pattern is barred

Brown back

Barred Head

Ngami Owlet (Glaucidium ngamiense)

Also known as the Bar-Fronted Owlet

This owlet has a large range and can be seen in many regions across Sub-Saharan Africa such as northeastern South Africa, Swatini, southern Mozambique, northwest Zimbabwe, northern Botswana, northern Namibia, south-central Angola, southeast Democratic Republic of the Congo, northern Mozambique, and southern and western Tanzania

Viewed as a subspecies of the African Barred Owlet

Albertine Owlet (Glaucidium albertinum)

Also known as Prigogine’s Owlet

Seen as a separate species despite the little data that is available

Specimens found in the Albertine Rift in the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo, Rwanda, and Uganda

Has a plain, warm chestnut-brown back and uppertail-coverts

Short tail that is smaller than the wings

Smaller number of pale bars on the tail, head, and neck

More bars on the back, especially on the uppertail-coverts

White spotting on the head and neck that differentiates this owlet from other species

Plain, unbarred chestnut back and uppertail-coverts

Hindcollar is barred white

Specimens found have variation with regards to the color of the spots on the outer webs of the scapulars and greater wing-coverts

Forehead, crown, and neck are mostly dark brown

Crown has white spots that widen on the hindneck that extend to the lower collar and neck to form bars

The lower mantle, back, rump, wings, and uppertail-coverts are a dark, chestnut brown that is warmer in tone than the head and neck

Scapulars have a large, bright white subterminal patch that is more extensive on the outer web, the tip, inner fringe, and base of which is very dark in color

The fine cream spotting of the crown and nape is the main distinguishing feature that sets this species apart from the African Barred Owlet

This owlet is unknown in the field with no documented sightings

According to Fishpool (2023), who did an exhaustive analysis of this species, argues that the calls recorded that were attributed to the Albertine Owlet were misidentified with those of other species

He further states that this bird's call does not have enough variation in structure or tempo to be a separate species

Found in three mountain ranges that border Itombwe in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Nyungwe in Rwanda, and the mountains west of Lake Edward

Specimens found at an elevation between 1,120-2,500 m at Lundjulu, Musangakye, and Nyungwe near the border between Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of the Congo

This species prefers lowland equatorial, transition, and montane forests

The Albertine Owlet shares the same habitat as the Chestnut Owlet

Any sightings or recording of this species could be confused with the Chestnut Owlet since previously specimens of the former were confused with those of the latter in museum collections

Etchecopar’s Owlet (Glaucidium etchecopari)

Seen in Côte d’Ivoire, Liberia, Ghana, Togo, and Benin

Seen as a subspecies of the African Barred Owlet

Scheffler’s Owlet (Glaucidium scheffleri)

This owlet can be seen in northeast Tanzania, southeast Kenya, and the extreme southern coast of Somalia

Seen as a subspecies of the African Barred Owlet

Head and neck pattern is mainly spotted

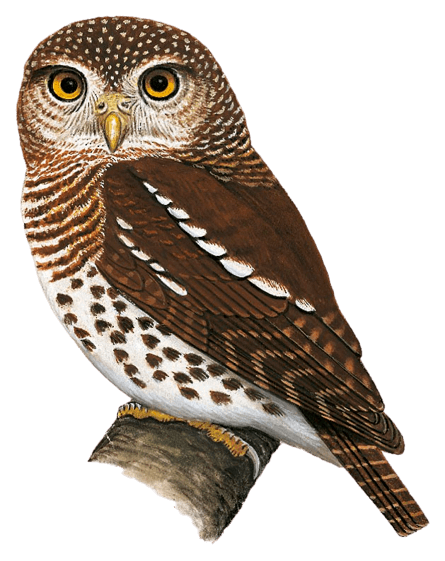

Chestnut Owlet (Glaucidium castaneum)

20-21.5 cm in length

Head and neck pattern is mainly spotted than barred like Scheffler’s Owlet

Disagreement over whether or not the Chestnut Owlet is a distinct species with some taxonomies treating this species as a subspecies of the African Barred Owlet

This species main feature is the back that is a dark chestnut with the neck and head having the same color

Spotted head that is not barred like the African Barred Owlet

Similar in appearance to Scheffler’s Owlet in terms of the pattern and extent of the white spotting on the head and neck, and the slight barring on the back

Much smaller in size compared to the African Barred Owlet

The species’ size is in the middle between that of Etchecopari’s and Scheffler’s Owlets

Brown facial disk marked with dark bars and flecks

Whitish eyebrows

Chestnut upperparts

White shoulder line formed by the outer wens of the scapulars

Pale underparts are marked by a dense barring on the breast with spots on the rest of the underparts

Yellow eyes

Cere and bill are a greenish-yellow

Legs and toes are feathered, bristly, and dirty yellow in color

Shares the same habitat as the Albertine Owlet (i.e., lowland equatorial, transition, and montane forests)

This species biology is unknown but is thought to be partly diurnal like the African Barred Owlet

Eats small mammals and insects

The only specimens of this species were found in Semliki in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and the Bwamba Forest in Uganda

Specimens found at an elevation between 710-915 m (Fishpool, 2023)

Life span 3.8 years (IUCN Red List)

Conservation Status

The Chestnut Owlet is listed as Least Concern by the IUCN that made its last assessment in 2018. The species has this classification due to the bird’s supposedly large range and the fact that there is no evidence for this bird to be classified as Vulnerable according to the IUCN’s thresholds. So much is unknown about this bird, especially its population size. All that is known about the Chestnut Owlet comes from only a handful of specimens. The species is thought to be in decline due to the rising rate of habitat loss that is many regions of Sub-Saharan Africa (IUCN Red List). This conclusion is based on a study done by Tracewski et al. (2016) that used remote sensing data on land cover change in conjunction with the species’ distribution ranges found on the IUCN’s polygon maps in order to analyze rates of habitat loss in several global regions, including Sub-Saharan Africa. They argue that the degree of forest loss in the period between 2000-2012 led to the extinction risk of 16 species of amphibians, birds, and mammals worldwide with many more species facing rapid rates of forest loss during the period. While they did not mention the Chestnut Owlet by name, they noted that one of the highest rates of forest loss occurred within the species’ range. Based on this, one can infer that the Chestnut Owlet may be vulnerable due to habitat loss despite the IUCN’s assessment.

Last Documented

Assuming this bird is restricted to Uganda and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the last specimen may be from December 1968. Confusingly, however, we note that there are recordings of a similar owlet from northeastern Rwanda (e.g., July 2021 and January 2022), which is also outside the mapped range of that species.

Since the Chestnut Owlet was first described, there has been a storm of controversy over her classification. This species taxonomic history has been fraught with misidentifications, unverified accounts, mapping errors, and some specimens of this species being confused for another. The fact that the Chestnut and Albertine owlets are so similar in appearance has only created more confusion for taxonomists. This was combined with the fact that, since the 1980s, simultaneous descriptions of new subspecies of the African Barred Owlet led to some publications confusing one subspecies with another since they often had to work with limited or incomplete data in their analyses. At first, there were five specimens that were previously listed as Chestnut Owlets. After further analysis, it was revealed that four of these specimens were actually Albertine Owlets.

Currently, there are only four specimens confirmed to be those of the Chestnut Owlet. The first was found in 1891 in Andundi within Semliki in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and the second was found in 1968 in Ntandi within Bwamba, Uganda. Both areas were only 28 m apart from each other at an elevation of 700 m. Thanks to the efforts of Lincoln Fishpool who conducted a detailed analysis of all known museum specimens of the African Barred Owlet and her congeners, two other specimens of the Chestnut Owlet were found. These specimens were dated 1956 and 1958 and were collected in the Bwamba Forest in Uganda. These specimens were almost completely unknown to ornithologists due to the irregularities relating to who owned these specimens within museum collections. Due to the confusion with the Albertine Owlet, the areas where Albertine Owlet specimens were found were not taken off the range of the Chestnut Owlet. This continues to lead to confusion about the Chestnut Owlet’s range to this day since many publications and organizations have not updated their information.

In September and October 1989, Dr. Françoise Dowsett-Lemaire reported seeing small owls in the Nyungwe Forest in Rwanda that she theorized could be Albertine Owlets. Due to their similar appearance, there is also a chance these owls could be Chestnut Owlets as well. There have been other sightings before and after Dowsett-Lemaire's survey (1984-2018). The problem is that these sightings have little detail and are hard to verify (Fishpool, 2023). Other owlet populations were found in the Republic of the Congo, the Central African Republic, and Cameroon in the 1990s. One such population was found by Dowsett-Lemaire and Dr. R.J Dowsett in 1997 when 18 African Barred Owlets were spotted in semi-evergreen forest along 25 km of track between the Bomassa and Ndoki camps at Nouabalé-Ndoki National Park in the Republic of the Congo. The territories where the owlets were found were clustered with up to 6 birds occurring along a track 1.5 km long. This discovery came a year after the Dowsetts saw and recorded an African Barred Owlet at dusk in the same area in 1996 in a semi-evergreen forest with an open canopy near the Ndoki and Mbéli rivers. The owlets responded to playback from recordings taken of Etchecopar’s, Ngami, and African Barred owlets. They suspect that these owlets are Chestnut Owlets and might also be found in the northern edge of the Guineo-Congolian forest block in Congo-Kinshasa to form a continuum with other populations in Central Africa. The Dowsetts were not able to determine the identity of the owlets they discovered at Nouabalé-Ndoki (Dowsett-Lemaire and Dowsett, 1998). These populations have yet to be thoroughly studied. Until they are, the possibility exists that some or all of these populations could be Chestnut Owlets.

To date, there is no evidence of the Chestnut Owlet from the places where the specimens were collected. No recordings exist of this species. Other than the accounts by Dowsett-Lemaire and others in Nyungwe, unidentified owls were either seen or heard in areas such as the Semliki Valley (April 23, 1998 and January 24, 2011) and the Mubwindi Swamp in Uganda. The details of these accounts are scarce and misidentification could be a possibility, especially in the last case where the sighting occurred at an elevation that is much higher than that reported for the species as well as the fact that this area has been greatly surveyed by researchers.

Due to the confusion surrounding the species, publications have not been kept up to date with recent discoveries. One such discovery is that Etchecopar’s Owlet was seen in a much larger range than previously thought in countries such as Ghana, Togo, and Benin. This extends this subspecies’ range eastward towards that of the Chestnut Owlet which is limited to Semliki in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. This overlapping of ranges could lead to further confusion with regards to accurately identifying the Chestnut Owlet in the field.

In 2023, Dr. Lincoln Fishpool conducted perhaps the most thorough analysis of Chestnut Owlet specimens to date. His findings indicate that the Chestnut Owlet is not a distinct species at all but a subspecies of the African Barred Owlet, "the paucity of museum material, the lack of any acoustic evidence for castaneum [Chestnut Owlet] and indeed, as detailed above, of field observations of either have to be borne in mind when seeking to draw conclusions....That said, on the basis of current knowledge, castaneum can be considered no more than a (modestly distinct) subspecies..... in the absence of vocal evidence there is therefore no justification to recognise castaneum as a species." Fishpool points to the fact that the Chestnut Owlet’s only real distinguishing features are the bird’s small size and the warm, chestnut color of her back. He argues that, in fact, the Albertine Owlet has more of a chance of being a separate species. This is due to the fact that this bird does not respond to playback and has unique spotting on the scapulars and greater wing-coverts that are buff, white, or a mix of both compared to these areas being uniformly white with other subspecies of the African Barred Owlet (Fishpool, 2023).

Challenges & Concerns

The greatest challenge the Chestnut Owlet must face is the high rate of habitat loss that is happening across her range. This habitat loss is caused not only by agricultural expansion but also by the indirect and direct impacts continuous armed conflict has had on diverse ecosystems in the DR Congo. During a wartime situation, there are several ways an armed conflict can negatively affect wildlife. Animals can be accidentally killed by mines or shells. They can be hunted and overexploited to feed troops. If they are an endangered species, they can even be used by hostages or pawns to hamper government troops or gain international support. War can affect park institutions in a reserve where endangered and vulnerable species are protected. Rebels can occupy an area and chase park officials away. With park institutions absent, this not only opens the door for rebels and poachers but also refugees from neighboring regions affected by the conflict to come in and overexploit park resources and destroy natural environments (Gaynor et al., 2016). All of these factors either have happened or continue to happen on some level in the DR Congo ever since the country ceased to be a Belgian colony in the 1960s. The armed conflict that has ravaged the country does not show signs of ending anytime soon. While large mammals tend to be the center of attention for economic reasons such as poaching, birds can be the target of poaching and habitat loss as war forces many in the country to overexploit resources to survive.

The DR Congo has among the richest and diverse ecosystems in the world. Ironically, these areas are also among the most poorly studied and ravaged by habitat loss as a result of the incessant warfare that has plagued the country since independence. The Chestnut Owlet is one of 13 rare species that are either only known from the DR Congo or are mainly known from this region. Other than the Chestnut Owlet, the list includes the Itombwe Nightjar, Itombwe Owl, Grauer’s Cuckooshrike, Lendu Crombec, Kabobo Apalis, Prigogine’s Greenbul, Sassi’s Greenbul, Chapin’s Mountain Babbler, Prigogine’s Sunbird, Upemba Masked Weaver, Black-Lored Waxbill, and Yellow-Legged Weaver. It appears that more and more of their habitat is destroyed by agriculture and overexploitation and more and more of their members are captured or killed due to poaching and hunting with every passing year. If the armed conflict in the DR Congo does not cease, it is unsure how much longer these rare species can continue to cope with the direct and indirect impacts war has had on their survival.

Research Priorities

According to Fishpool (2023), subspecies of the African Barred Owlet have been known to respond to playback of recordings of other subspecies. The exception is the Albertine Owlet that supposedly does not respond to playback. This might prove true for the Chestnut Owlet. Further research is needed to prove this theory.

DNA analysis needs to be done on one or all of the four known specimens of the Chestnut Owlet. This analysis can help resolve the controversy surrounding this species as well as confirm or refute Fishpool’s claim that this bird is a subspecies of the African Barred Owlet.

Taxonomy

There is considerable debate surrounding the Chestnut Owlet’s status as a distinct species with several taxonomies treating the bird as a subspecies of the African Barred Owlet (Birds of the World).

Page Editors

- Nick Ortiz

- Search for Lost Birds

Species News

- Nothing Yet.

Support The Search for Lost Birds

Donations from supporters like you make expeditions, science, and conservation possible. Help support the Search.