Kabobo Apalis

Apalis kaboboensisFAMILY

Cisticolas and Allies (Cisticolidae)

LAST DOCUMENTED

2007

(19 years)

REGION

Africa

IUCN STATUS

Vulnerable

Background

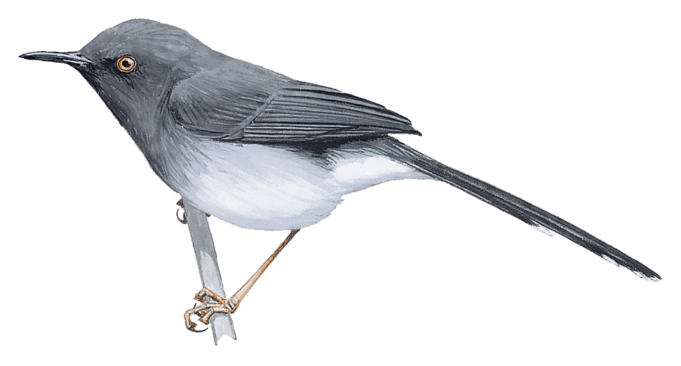

Description

12 cm

Grey forest apalis

Long and graduated blackish tail narrowly tipped whitish

Blackish-slate head and upperparts

Blackish-slate throat and upper breast that merges into pale grey on lower breast

Blackish-slate belly and vent

White underwing-coverts

Reddish-brown iris

Black bill

Yellowish-pink legs

Females are a paler grey above, on throat, and on breast as well as have a whitish belly

Juveniles are washed olive above and have a creamy olive throat, olive-grey breast, greenish belly, and a pale brown bill

Juvenile males have a paler crown and throat

Due to the similarity in appearance and range, this species is treated by many as a subspecies of the Chestnut-Throated Apalis (Apalis porphyrolaeme) and by some as conspecific to Chapin’s Apalis (Apalis chapini)

The Chestnut-Throated Apalis can be found across Burundi, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DR Congo), Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania, and Uganda in highland forests above 1,600 m

Chapin’s Apalis is found in Malawi, Tanzania, and Zambia in tropical montane forest

The Kabobo Apalis differs from the Chestnut-Throated Apalis by being smaller in size, having a shorter wing and tail, a grey throat (instead of chestnut), paler underparts, and a darker grey breast

Males from this species are slightly paler and more olive above than their Chestnut-Throated counterparts

Females from this species differ from Chesnut-Throated females by having a paler greyish-white throat

A juvenile Kabobo Apalis differs from a juvenile Chestnut-Throated Apalis by having a yellowish-olive throat instead of a cream buff one

Habitat

This species is known from only the Misotshi-Kabogo region (also known as Mt. Kabobo) in the DR Congo

Preferred habitat is the canopy of montane forest between 1602-2691 m

Vocal Behavior

In 2007, the song of the Kabobo Apalis was recorded for the first time

This bird does a series of chirps and trills in her song that are similar to those seen in the song of the Chesnut-Throated Apalis

The song is a duet with one bird giving one or two chirps and the other doing a trill

The timing is precise

The Kabobo Apalis belongs to the Chestnut-Throated Apalis vocal group

There is variation in the song structure relating to the sequence of the chirp notes, the duration, and number of elements in the trill

The song phrase is shorter and often preceded by 2 chirps, then a trill, and ended by a chirp (the second chirp and trill run together) (Plumptre et al., 2008)

Other Information

Other than observations that this bird gleans from leaves and branches, the diet of this species is unknown

While the behavior of this species is unknown, some speculate that (like the Chestnut-Throated Apalis) the Kabobo Apalis probably works in pairs or in small family parties (Butchart, 2007)

Breeding behavior unknown (Birds of the World)

Life span- 2.4 years (IUCN Red List)

Conservation Status

The Kabobo Apalis has been classified as Vulnerable by the IUCN that made its last assessment in 2020. The species is only known to inhabit the montane forests of the Misotshi-Kabogo region west of Lake Tanganyika in eastern DR Congo. It is for this reason that the population is believed to be small and declining due to habitat loss, population growth, and agricultural expansion. The species’ range of occurrence is 1,800 km2 (IUCN Red List).

According to a study by O. Dewhurst (2019) who used distance sampling to estimate population sizes for birds across various regions in the Albertine Rift, there are approximately 4,130 individuals of the Kabobo Apalis species in the Kabobo-Marungu area in the Albertine Rift.

For a distribution map of the Kabobo Apalis, click here.

Last Documented

The Kabobo Apalis was first described by Alexandre Prigogine in 1955. He described the species after examining the specimens collected by Belgian researchers during the 1950s and comparing them to known specimens of the Chestnut-Throated Apalis, Chapin’s Apalis, Apalis affinis, and Apalis strausae (the latter two subspecies of Chapin’s Apalis). Whereas most of the specimens had a chestnut chin and throat, what made the specimens of the Kabobo Apalis different was the blackish grey throat that did not match any known Apalis populations in the Misotshi-Kabogo region. He concluded that the Kabobo Apalis’ morphological differences was due to the fact that this bird’s evolutionary process diverged from that of other Apalis species and was, therefore, a distinct species (Prigogine, 1985).

After Prigogine’s description of the species, his assertion came under attack from other ornithologists (such as B.P Hall and R.E Moreau) who insisted that there was not enough evidence to sustain the claim that the Kabobo Apalis was a separate species. They argued that the bird was a subspecies of the Chestnut-Throated Apalis. Over the years, two camps formed between ornithologists. One camp sided with Hall and Moreau in treating the Kabobo Apalis as a subspecies of the Chesnut-Throated Apalis or as conspecific with Chapin’s Apalis while others, such as James Chapin, sided with Prigogine in asserting that the bird was a distinct species. Due to the political instability in the DR Congo, surveys in the Misotshi-Kabogo region became impossible as well as finding further evidence that the bird was even alive much less a distinct species.

In 2007, more than 50 years after the last survey in the region, a team led by Andrew Plumptre surveyed the Misotshi-Kabogo and the Muganja Hills with the backing of the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS). An aerial survey revealed that these parts were the only areas that were not completely deforested as a result of encroachment and agricultural/pastoral expansion. They saw that the Marungu Massif was almost completely converted into farmland and pastures. All that remained was a large area of Miombo woodland and riverine forest around the Muganja Hills north of Marungu and the Misotshi-Kabogo region that still had the largest forest block on Lake Tanganyika that remained by human activity. The goal of the survey was to assess the conservation value of the Marungu Highlands and the Misotshi-Kabogo region with particular interest in the chimpanzee populations in these two areas. The survey took place in the Misotshi-Kabogo region from January 28-February 26, 2007 and the Muganja Hills between March 4-18, 2007.

The survey was a resounding success. Plumptre and his team found many mammals (including signs of chimpanzee nests), a new species of bat, and two new amphibian species. Perhaps one of the most important finds of the team was confirming that the Kabobo Apalis was still in the Misotshi-Kabogo region where she was first recorded more than 50 years earlier. Besides the Kabobo Apalis, Plumptre and his team used mist nets and recorded bird calls in the Misotshi-Kabobo region to find 74 species of birds that were never before recorded for that region. To see a map of the sites they investigated, click here.

They reported the Kabobo Apalis as common in the canopy (1602-2691 m). Elia Mulungu recorded the bird’s song and compared it to that of Chestnut-Throated Apalises from Rwanda and Kenya. Based on the recordings, Plumptre and his team concluded that the Kabobo Apalis is a subspecies of the Chestnut-Throated Apalis due to similarities in vocal patterns. In addition to recording the bird, Plumptre and his team took a picture of a juvenile Kabobo Apalis and recorded key information on the species’ movements. They note that the Kabobo Apalis is unlikely to occur in the gallery forest in the west of the main forest block at 1,500 m and is confined to the forest block in the Misotshi-Kabogo region. This forest block was not under threat as other areas in the Albertine Rift. Other than some signs of hunting, logging, and mining, no permanent villages were present in the region with only temporary military camps, mining settlements, and fishing villages on the lake shore (all of which had a minimal impact on the forest).

In 2016, 11 years after the survey led by Plumptre, the Misotshi-Kabogo forest block became protected land within the boundaries of the Kabobo Natural Reserve. Assuming that the area still remains protected and is minimally affected by human impacts, even though the Kabobo Apalis has not been seen since 2007, it stands to reason that the bird is still there waiting for a new survey team to check up on her (Plumptre et al., 2008).

Challenges & Concerns

The Kabobo Apalis’ range lies within the Albertine Rift. This is a region that has been praised for being a biodiversity hotspot that boasts one of the highest levels of biodiversity on the African continent. However, it is also a region that has been negatively affected by population growth, climate change, encroachment from neighboring villages, and agricultural expansion in recent decades. According to S. Ryan et al. (2017), international market forces and local demand are driving the conversion of forest into tea farms and pastures with tea farms alone accounting for 1.90% forest loss per year. This has affected forest cover change across the Albertine Rift. They argue that, "a dynamic process of forest cover gain and forest cover loss is occurring on the landscape, with different drivers emerging at local and national scales, and signals of higher rates of forest cover loss, but greater areas of forest cover gain." Population growth in the DR Congo is the biggest driver of forest loss with a doubling in population expected to cause 2.06% forest loss per year locally. Paradoxically, this increase in population density at a local level was associated with lower rates of forest cover loss but also mitigated forest cover gain. Interestingly, they also argue that forest cover gain was influenced by the stable production of certain crops such as cassava (Ryan et al., 2017).

What is concerning is that most of the forest in the Albertine Rift has been converted into farmland or pastures. According to a survey conducted by Plumptre et al. (2008), the forest block in the Misotshi-Kabogo region where the Kabobo Apalis is located was unaffected by the destructive phenomena plaguing other areas in the Albertine Rift where entire areas were deforested. This survey was 16 years ago. Since then, the Misotshi-Kabogo region has been included within the Kabobo Natural Reserve that was established in 2016. It is unclear how well the reserve has protected this forest from agricultural expansion and encroachment.

The habitat loss caused by the indirect and direct impacts continuous armed conflict has had on diverse ecosystems in the DR Congo is another challenge the Kabobo Apalis must face. During a wartime situation, there are several ways an armed conflict can negatively affect wildlife. Animals can be accidentally killed by mines or shells. They can be hunted and overexploited to feed troops. If they are an endangered species, they can even be used by hostages or pawns to hamper government troops or gain international support. War can affect park institutions in a reserve where endangered and vulnerable species are protected. Rebels can occupy an area and chase park officials away. With park institutions absent, this not only opens the door for rebels and poachers but also refugees from neighboring regions affected by the conflict to come in and overexploit park resources and destroy natural environments (Gaynor et al., 2016). All of these factors either have happened or continue to happen on some level in the DR Congo ever since the country ceased to be a Belgian colony in the 1960s. The armed conflict that has ravaged the country does not show signs of ending anytime soon. While large mammals tend to be the center of attention for economic reasons such as poaching, birds can be the target of poaching and habitat loss as war forces many in the country to overexploit resources to survive.

The DR Congo has among the richest and diverse ecosystems in the world. Ironically, these areas are also among the most poorly studied and ravaged by habitat loss as a result of the incessant warfare that has plagued the country since independence. The Kabobo Apalis is one of 13 rare species that are either only known from the DR Congo or are mainly known from this region. Other than the Kabobo Apalis, the list includes the Itombwe Nightjar, Itombwe Owl, Chestnut Owlet, Grauer’s Cuckooshrike, Lendu Crombec, Prigogine’s Greenbul, Sassi’s Greenbul, Chapin’s Mountain Babbler, Prigogine’s Sunbird, Upemba Masked Weaver, Black-Lored Waxbill, and Yellow-Legged Weaver. It appears that more and more of their habitat is destroyed by agriculture and overexploitation and more and more of their members are captured or killed due to poaching and hunting with every passing year. If the armed conflict in the DR Congo does not cease, it is unsure how much longer these rare species can continue to cope with the direct and indirect impacts war has had on their survival.

Some speculate that the Kabobo Apalis might face competition from the Chestnut-Throated Apalis since the ranges of the two may overlap in the Misotshi-Kabogo area. The Kabobo Apalis is recorded to appear at an altitude range between 1602-2691 m. While the Kabobo Apalis prefers the canopies of montane forests, the Chestnut-Throated Apalis has a wider habitat range that includes montane forests, second-growth forests, gallery forests, forest edges, medium-sized trees, and liana tangles (Butchart, 2007). If there are Chestnut-Throated Apalises in the region, this means the two species might compete in tropical and bamboo forests that are at an altitudinal range greater than 1,400 m (Dewhurst, 2019). As of yet there have been no reports of Chestnut-Throated Apalis recorded in the Misotshi-Kabogo area. The most recent survey by Plumptre and his team (2008) did not report any members of this species in this area either.

Research Priorities

Launch a new survey into the Misotshi-Kabogo region to see if the area has suffered from any deforestation and whether or not the Kabobo Apalis is still there.

Conduct a DNA analysis of the 19 known specimens of the Kabobo Apalis to see whether or not there is enough genetic divergence to justify this bird’s status as a distinct species or to prove that this species is a subspecies or conspecific with the Chestnut-Throated Apalis or Chapin’s Apalis respectively.

Ongoing Work

In December 2016, after decades of planning between conservationists, local communities, ornithologists, and government officials, the governor of the Tanganyika Province in the eastern DR Congo (Richard Kitangala) approved the boundaries of a new reserve that included the Misotshi-Kabogo region. This new Kabobo Natural Reserve covers 1,477 km2 and was the first protected area to be created in the province. Since 2009, the WCS was heavily involved in this effort to create a natural reserve that covered one of the most important biodiversity hotspots in Africa. The WCS worked together with local communities to protect the boundaries of the proposed reserve before it became legal in 2016. Local communities, such as the Batwa pygmy groups, had a say in the boundaries of the reserve and how the reserve would be managed. These same local communities now participate in the reserve’s enforcement and protection. The Kabobo Natural Reserve borders two other reserves: Luama Katanga and Ngandja. Together these reserves compose a protected area 25 times the size of the country of Burundi (6,951 km2). The creation of this reserve was part of a 7-year plan in the DR Congo to encompass 17% of the country within protected natural reserves. Thanks to this reserve, the Kabobo Apalis’ territory now lies within a protected reserve; greatly increasing her chances of survival (Mongabay News).

In February 2017, a survey was launched by MUSE, the WCS, the University of Verona, Italy, and Personal Genomics to investigate an unexplored strip of montane rainforest in the Kabobo Massif. This massif is a small range of mountains 100 km along the western shore of Lake Tanganyika that forms the border between the DR Congo, Burundi, Tanzania, and Zambia. This survey seeks to build on the one done by Andrew Plumptre and his team in the Misotshi-Kabogo region and the Muganja Hills. The results of this survey are still pending (Mongabay News).

Taxonomy

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Cisticolidae

Genus: Apalis

Species: Apalis kaboboensis/Apalis porphyrolaeme kaboboensis/Apalis chapini*

*There is disagreement among taxonomists regarding this species’ status. Some believe the morphological differences are enough to make the Kabobo Apalis a distinct species. Others argue that the bird is a subspecies of the Chestnut-Throated Apalis. There are also some that think this bird is conspecific with Chapin’s Apalis.

Page Editors

- Nick Ortiz

Species News

- Nothing Yet.

Support The Search for Lost Birds

Donations from supporters like you make expeditions, science, and conservation possible. Help support the Search.