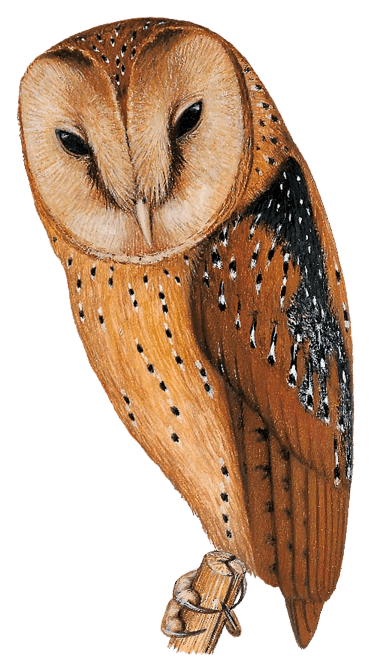

Itombwe Owl

Tyto prigogineiFAMILY

Barn-Owls (Tytonidae)

LAST DOCUMENTED

1995

(31 years)

REGION

Africa

IUCN STATUS

Data Deficient

Background

Basic Description

Also known as the Congo Bay Owl or Prigogine's Owl

23-29 cm

195 g

Only one single female specimen has been found

Feather tips have small black-edged white spots

Wings and tail are barred dark brown

Facial disc is a light, rufous brown with a darker rim

Breast and flanks are a finely spotted dark brown or black

Irides is dark brown to blackish

Bill is yellowish

Toes are yellowish-grey and bare

Heart-shaped facial disc with dark eyes

Differs from Oriental Bay Owl (Phodilus badius) in that it has a heart-shaped facial disc, no ear tufts, and small eyes (Birds of the World)

Metatarsus is well-feathered

The talon of the middle toe has a sharp ridge on its inner side which becomes pectinate distally

The Itombwe Owl also differs from the Oriental Bay Owl in that this bird is darker in color, has a more compressed beak, and smaller feet (Chapin and Lang, 1954)

Life span 5.9 years (Data Zone-Birdlife International)

Chestnut brown

Rusty brown above with paler orange parts

Only specimen found at Muusi in the Itombue Mountains, Democratic Republic of the Congo (IUCN Red List)

Schouteden's Description of the Muusi Specimen

The middle talon is pectinate (or serrated like the teeth of a comb) like a Tytonid, a trait that is also shared by the Oriental Bay Owl

Top of the head is brown that extends to the base of the beak

Feathers have a black spot at the end that surround a reddish smudge

This black spot is preceded by another spot on the spine where both are separated by a reddish space

The spots are more developed on the back of the head with the black spot being bordered in the front and in the back by a reddish color

Some feathers have a black spot

The neck has a bronze yellow color

Feathers have a lighter tint and have a black spot at the end in the front and in the back

Sides of the neck have the same color with simple black spots on the feathers

A warm brown color on the top of the back that matches the top of the head with similar, larger spots

The rest of the back is darker with the back feathers dark with brown and reddish speckles

Reddish or whitish spot at the spine

The underparts are similar

Scapulars also have blackish coloring with a grey speckle

A small light middle, apical spot before a larger spot at an angle that stands out from a black background

Tail feathers are duller brown with dark speckles

Each tail feather has 7 black bands across the length

Black spot surrounded by white at the end of the spine

The first tail feather outside is brighter and looks flavescent

Large and middle wing coverts are brown with a black apical spot

The spine is light and marked with black

The base of the feathers are a flavescent reddish with irregular black bands crossing them

The outer and small coverts are covered with black or are speckled like the scapulars with white or ferruginous spots

The large, outer coverts are black with a brown border spotted with black and showing an apical black spot surrounding a white spot

Primary flight feathers are chestnut brown

The outer dewlap has 6-8 black bands

The inner dewlap has a lot of black with black bands from the outer dewlap

The ends of the flight feathers are chestnut brown

The secondary flight feathers have the same general color but with less black at the inner dewlap

The feathers on the inside of the body have the same color as the scapulars and the back with the outer dewlap being, to a large degree, black speckled with white or reddish with two apical white spots appearing and separated by a black facial disc

The internal edge of the eye has a small black mark that is surrounded by black

The feathers around the collar are white with black or darkish brown tips

The bottom of the body is a lot less colored that the top and is duller with a basic coloration that is blond-reddish mixed with fine brown spots or black spots on the stomach

The chest is a golden yellow color

The feathers on the stomach are often darker with light speckles

Each feather has a black spot surrounded by white or reddish

The feet are like the stomach but less speckled, especially the tarsus

The beak is more compressed than the Oriental Bay Owl

The upper mandible is 6 mm in length and appears streamlined

The talons are shorter and the claws are less sharp

Wing span- 193 mm

Tail- 93 mm

Tarsus- 45 mm

Beak-25 mm

Main distinction from the Oriental Bay Owl is the chestnut brown color at the top of the head that extends to the base of the beak (Shouteden, 1952)

Habitat

This species is present in the Itombwe Massif and perhaps in southwest Rwanda (Nyungwe forest) and northwest Burundi (near Teza)

Prefers montane forest with bamboo thicket and grassland between 1830-2430 m that includes selectively logged areas

Other Information

Diet is unknown but the long legs indicate that the owl does a lot of ground hunting

Vocal behavior is unknown but a recording from Rwanda suggests a wok-wok-wok call similar to the Oriental Bay Owl

Breeding habits are unknown but this owl supposedly nests in tree cavities (Birds of the World)

Conservation Status

The Itombwe Owl is classified as Data Deficient by the IUCN.

Previously listed as Endangered, the status was changed to Data Deficient in 2025 to reflect the lack of information about the species.

The owl is thought to be range-restricted and have specific habitat requirements common to the Albertine Rift Mountains with a range of 4,700 km (Birds of the World). These include highlands, grasslands, montane forest, and bamboo forest. The owl is likely to be found between 1,800-2,400 according to where the only specimen was found along with eyewitness accounts. Many argue that the Itombwe's Owl range may be much farther than originally thought and that it extends into Burundi and Rwanda (especially the Nyungwe Forest). It is also possible that this species can tolerate disturbed habitat to a certain extent since the Itombwe Owl that was captured in a mist-net in 1996 was found in a slightly disturbed area (IUCN Red List). The population size is estimated at 9,360 individuals. For a distribution map of the Itombwe Owl's known range, click here.

Last Documented

Known with certainty from only two records in the Itombwe Mountains of eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo. The type specimen was collected in March 1951 and, much more recently, another was photographed (May 1996) after being captured in a mist net (Butynski et al. 1997).

The Muusi Specimen

The Itombwe Owl was first described as a species by Dr. H. Schouteden at the Musée du Congo Belge in Tervuren, Belgium. The only female specimen was found in a place called Muusi in the Itombwe Massif off the northwest corner of Lake Tanganyika within the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo. He (1952) described the species as, "a new species completely distinct from other African Strigids and not related to any of the known species in Sub-Saharan Africa" (Translation from French by Nick Ortiz). To date, this species is the only bay owl known to inhabit the African continent. Since the species was first described in March 1951 by Dr. H. Schouteden, there have been many unsuccessful attempts (1952-1964) to find this bird in the montane forests of the Albertine Rift. Some of these attempts were by the very collector for whom the owl was named after, Alexander Prigogine. The original specimen was found at a grass clearing at 2,430 m.

The Burundi Sighting

On December 15, 1974, L. and P. Browne had a potential sighting of an Itombwe Owl in a small patch of forest near a tea estate in Teza, Burundi. This estate was near the Congo-Nile watershed at 2,500 m, 25 km south of Rwegura and 85 km east of Muusi where the first Itombwe Owl specimen was found. At 3 p.m., the Brownes were bird watching when they saw an owl they had never seen before perched on a branch 3 m from the ground. They were able to approach this bird at close range before she flew away. According to them, this bird looked like a small Barn Owl (Tyto alba), was 25 cm in length, had a buff, heart-shaped face with dark eyes, no ear tufts, a short tail, mottled reddish-brown and black upperparts, and buff underparts that were spotted with black. They never saw the same owl again when they went back to the same area the next year in 1975. They described the forest where they saw the owl as located on a steep, sloping terrain where a trail entered the forest downhill from a highland grassland habitat. It extended on both sides like the Nyungwe Forest in southwest Rwanda (which is located 50 km northwest of Teza along the Congo-Nile watershed). The owl was 100 m or less near the edge of the forest. The forest had mixed species of large and small trees with little underbrush and a dense canopy. To this day, the Brownes are convinced that what they saw was an Itombwe Owl because they saw the bird in a montane forest/grassland habitat (the same mosaic habitat that Butynski and others would see the same bird in decades later). The size and description of the bird also matched other accounts. The main characteristics were the heart-shaped facial disk, the lack of ear tufts, and the chestnut brown color. It is interesting to note that the Brownes did not see any spots on the bird's underparts and that the bird they saw did not correspond to the Muusi specimen but, instead, with the owl seen by Butynski and his team at Itombwe. The one seen by Butynski and his team had dark russet/creamy underparts with black streaks on the belly. This matched what the Brownes saw that day in Burundi (Browne and Browne, 2001).

The Mysterious Owl of Nyungwe Forest

From January-February 1990, there were two unconfirmed records close to the Albertine Rift at 2,000 and 2,500 m respectively. During that same year, Dr. F. Dowsett-Lemaire and her husband, R.J Dowsett recorded a mysterious owl in the Nyungwe Forest (2,000 m) in Rwanda (Butynski et al., 1997).

Return to Itombwe

During April-May 1996, the Wildlife Conservation Society conducted a biological survey of southern Itombwe where they investigated grassland, gallery montane forest, montane forest, and bamboo forest habitats between 1,130-2,350 m. On May 1, 1996, while using mist-netting to see what species were in the area, the team led by Dr. Butynski found an Itombwe Owl that was caught in a mist-net in the southeast corner of the Itombwe Forest in the Albertine Rift. The net was placed 50 m within a fairly dense, slightly degraded forest. The environment was a montane gallery forest at 1,830 m where the hilltops and upper slopes were covered with grass and light bush and the lower slopes with montane forest. This was near a sector that the team labelled Sanje-Upper Mutambala (Omari et al., 1999). This environment had slopes covered with grass and bushes and was nearby lower slopes and valleys also with montane forest (IUCN Red List). The owl flew 1.3 m above the ground when it was captured. Six pictures were taken of this owl and sent to Dr. Michel Louette (the same person who first described the Itombwe Nightjar six years prior). He confirmed that the owl they caught was indeed an Itombwe Owl. By what they could see, the owl was female, was 24 cm in length, had a 63 cm wingspan, weighed 195 g, and had a brood patch. They were able to measure, describe, and band the bird before releasing her back into the wild. After being released, the owl flew into a gallery forest. This bird was seen roosting in a grass clearing before flying 50 m inside a montane forest with wooded valleys and scrubby open tops. This encounter extends the species' known range further south 95 km and downwards with regards to its altitudinal range by 600 m. From what Butynski and his team could tell, the Itombwe Owl apparently needs a mosaic of grassland and forest (montane or bamboo) habitats to survive. The owl might rest in grasslands during the day and hunt in the forest at night. As far as Butynski and his team are aware, Itombwe is the only forest in Central Africa that has a large mosaic of vegetation typical of grassland, montane forest, and bamboo forest environments. They also noted that there is similar habitat in the Nyungwe Forest in Rwanda where the Dowsetts had an encounter with an unidentified owl six years before. Since the habitat where the owl was found was slightly disturbed, Butynski and his team concluded that this species will tolerate some human activity. In comparison with the Oriental Bay Owl, they noticed that the Oriental Bay Owl is lighter, has a less compressed bill, has larger feet and talons, is not known to appear above 1,500 m, and, unlike the Itombwe Owl, is not associated with a mosaic habitat. Butynski and his team never saw another Itombwe Owl during their survey (Butynski et al., 1997).

Challenges & Concerns

Forest clearing for agricultural purposes and grazing are a concern in the region (especially in Itombwe where the only specimen of this species was found). It is assumed that the Itombwe Owl is in decline due to habitat loss. The gallery forest in the central savanna plateau where the only specimen was found is being destroyed as we speak (IUCN Red List). Mining and hunting may also be factors that are exacerbating this species' decline (Birds of the World).

The greatest challenge the Itombwe Owl must face is the high rate of habitat loss that is happening across the DR Congo. This habitat loss is caused not only by agricultural expansion but also by the indirect and direct impacts continuous armed conflict has had on diverse ecosystems in the DR Congo. During a wartime situation, there are several ways an armed conflict can negatively affect wildlife. Animals can be accidentally killed by mines or shells. They can be hunted and overexploited to feed troops. If they are an endangered species, they can even be used by hostages or pawns to hamper government troops or gain international support. War can affect park institutions in a reserve where endangered and vulnerable species are protected. Rebels can occupy an area and chase park officials away. With park institutions absent, this not only opens the door for rebels and poachers but also refugees from neighboring regions affected by the conflict to come in and overexploit park resources and destroy natural environments (Gaynor et al., 2016). All of these factors either have happened or continue to happen on some level in the DR Congo ever since the country ceased to be a Belgian colony in the 1960s. The armed conflict that has ravaged the country does not show signs of ending anytime soon. While large mammals tend to be the center of attention for economic reasons such as poaching, birds can be the target of poaching and habitat loss as war forces many in the country to overexploit resources to survive.

The DR Congo has among the richest and diverse ecosystems in the world. Ironically, these areas are also among the most poorly studied and ravaged by habitat loss as a result of the incessant warfare that has plagued the country since independence. The Itombwe Owl is one of 13 rare species that are either only known from the DR Congo or are mainly known from this region. Other than the Itombwe Owl, the list includes the Itombwe Nightjar, Chestnut Owlet, Grauer’s Cuckooshrike, Lendu Crombec, Kabobo Apalis, Prigogine’s Greenbul, Sassi’s Greenbul, Chapin’s Mountain Babbler, Prigogine’s Sunbird, the Upemba Masked Weaver, the Black-Lored Waxbill, and the Yellow-Legged Weaver. It appears that more and more of their habitat is destroyed by agriculture and overexploitation and more and more of their members are captured or killed due to poaching and hunting with every passing year. If the armed conflict in the DR Congo does not cease, it is unsure how much longer these rare species can continue to cope with the direct and indirect impacts war has had on their survival.

According to experts, Itombwe is ranked as perhaps the single most important region for bird conservation in Africa despite its lack of conservation status. Its importance has only grown over the years as rapid agricultural expansion has devastated the gallery montane forests at its southern and western edges (Butynski et al., 1997). By the 1990s, half of the habitats in Itombwe had already been modified or degraded. Despite its importance in terms of conservation, many locals fear that the creation of a park in Itombwe might lead to them being expelled from their homes. This region (especially the Itombwe Massif in the African Great Lakes region) is one of the most densely populated and underdeveloped regions in Africa (Omari et al., 1999). The degree of habitat devastation is worse now due to higher rates of agricultural/pastoral expansion, hunting, and political violence. This a challenge since many endemic species cannot tolerate modified habitats. Due to the fact that the last Itombwe Owl was found in a disturbed habitat, it stands to reason that this species can tolerate modified habitats but no one knows to what extent.

An important area for this species in Itombwe is the Albertine Rift. Historically, this region was covered by montane forests with bamboo at higher elevations (1,600-3,500 m). Above the forest are Afroalpine grasslands, ericaceous shrublands, and moorlands. Within these environments, the rift itself is a series of mountain chains that border lakes in Central East Africa with a large part being present in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The mountains with a large concentration of endemic birds stretch for 1,200 km from the Lendu Plateau to the west of Lake Albert. The Itombwe Owl is seen to be a low-elevation, small-range species in the Albertine Rift. According to a study done by Bober et al. (2001), endemic birds in the rift that occur at higher elevations occupy more mountain ranges while those restricted to fewer mountain ranges have narrow altitudinal ranges on lower slopes. As far as they know, the Albertine Rift is not known to have any endemic birds restricted to high altitudes and that many montane species are capable of using lower elevation forest. This implies that the Itombwe Owl may have a wider range into other habitats. However, this poses a challenge towards this species' conservation since its need for mosaic environments implies that this species exists on both the upper and lower slopes of the rift. As of now, the lower slopes are more subject to deforestation than the upper slopes; a phenomenon that could be leading towards the decline of this species.

Research Priorities

Investigate which areas of Central Africa have mosaic environments that are suitable towards sustaining a population of Itombwe Owls. Itombwe does not have the only forest in Central Africa with a large area of highland forest and grassland. In Central Africa, locals, birdwatchers, researchers, and others should keep an eye out for a chestnut-colored owl and listen for long, mournful whistles or other calls that do match those of local species (Butchart, 2007).

Ongoing Work

Recently, Birdlife undertook a survey of Kibira (northwest Burundi) and Mt. Kabobo (Democratic Republic of the Congo) but were not successful in finding the Itombwe Owl (Birds of the World).

Taxonomy

Order: Strigiformes

Family: Tytonidae; Strigidae

Genus: Tyto; Phodilus

Species: Tyto prigoginei; Phodilus prigoginei

There is a fierce debate among taxonomists about where to place this species of owl. Led by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, many taxonomists see the Itombwe Owl has being relating to the Barn Owl (Tyto alba) and have placed this species in this family due to the common trait this species has with other species from this family (i.e. its middle pectinate talon). Others have followed the lead of Dr. H. Schouteden, the one who described the species in 1951. He placed the Itombwe Owl in the Strigidae family because of the bird's bone traits, shorter primaries, plumage, and completely feathered tarsus. He also included the species in the Phodilus genus because he saw it as a relative of the Oriental Bay Owl (Phodilus badius) (Schouteden, 1952). If the taxonomists who follow Schouteden's lead have their way, the Itombwe Owl will be one of three owls in this genus with the others being the Oriental Bay Owl and the Sri-Lankan Bay Owl (Phodilus assimilis). With so little information known about this species, this debate is likely to continue to range for years to come (Birds of the World).

Experts have noted that if it proves true that the Itombwe's Owl range indeed extends beyond Itombwe, then the species would need a more appropriate name. How the species is known now, such as the "Itombwe Owl" and the "Congo Bay Owl," would no longer be sufficient to account for its wider range outside Itombwe and the Congo River basin. According to them, in such a case, the species should strictly be known as the African Bay Owl or Prigogine's Owl (Browne and Browne, 2001).

Page Editors

- Nick Ortiz

- Search for Lost Birds

- John C. Mittermeier

Species News

- Nothing Yet.

Support The Search for Lost Birds

Donations from supporters like you make expeditions, science, and conservation possible. Help support the Search.