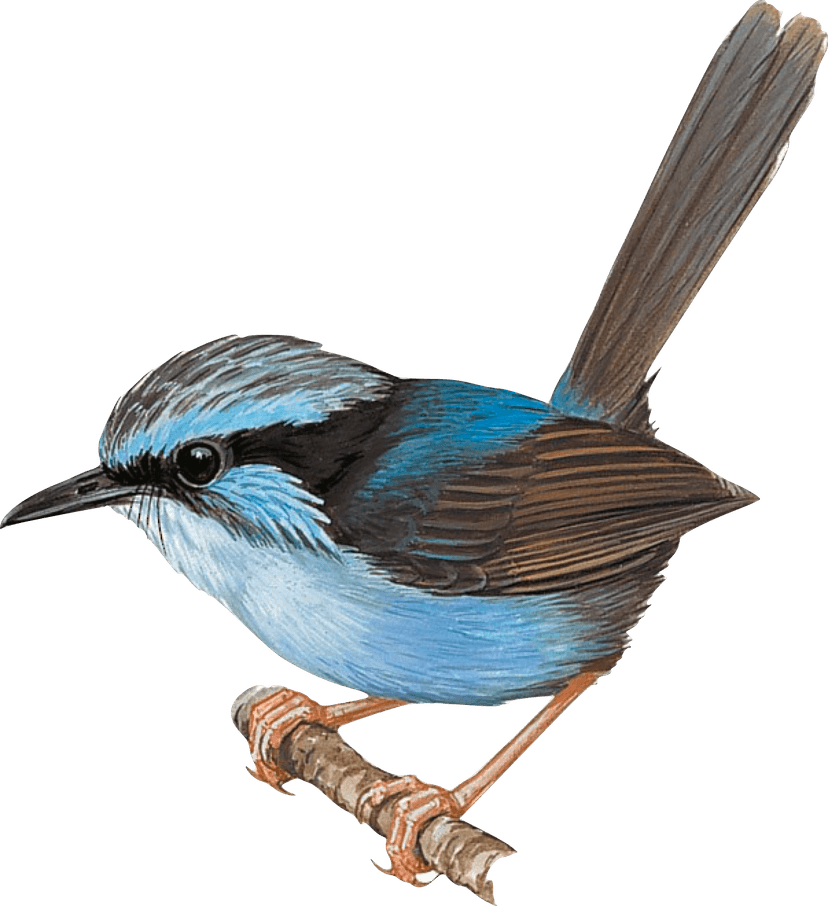

Broad-billed Fairywren

Chenorhamphus grayiFAMILY

Ducks, Geese, and Waterfowl

LAST DOCUMENTED

2015

(11 years)

REGION

Oceania

IUCN STATUS

Least Concern

Background

A poorly-known forest bird from northern New Guinea, there are a number of recent records of Broad-billed Fairywren but the most recent documented observations appear to be photographs taken in 2014.

Conservation Status

Broad-billed Fairywren is currently listed as Least Concern.

Last Documented

The last documented records of Broad-billed Fairywren appear to be photographs taken by Paul Sweet in October 2014. There have been a number of more recent sightings (in 2016, for example) , however, so it may only be a matter of time before this species is documented again.

Page Editors

- Search for Lost Birds

Species News

FOUND: Broad-billed Fairywren Documented in Indonesia After 11 Years

John C. Mittermeier / 29 Dec 2025

Read MoreEarlier this year, in the mountains of West Papua, Indonesia, the call of a fairywren brought Daniel Hoops to a halt. He expected the series of insect-like notes to belong to the Emperor Fairywren, a common species in the region. But on that March afternoon, he was thrilled to encounter a rare bird he had long hoped to see. With pale blue underparts, prominent black eye stripes, and brown wings, five Broad-billed Fairywrens darted through the forest before him.

“I couldn’t believe it,” Hoops reflects. “I’ve always been aware of the Broad-billed Fairywren. I asked several times if people had seen it, and they always said no. They didn’t know where to find it. It was a total shock, and a euphoric moment.” He didn’t know it then, but the species was also on the lost birds list, last documented in 2014. The following day, he would obtain the necessary evidence to reclassify the Broad-billed Fairywren from lost to found.

A postdoctoral neuroscientist at the University of Adelaide and an avid birder, Hoops often travels to New Guinea in search of birds and other wildlife. He visited the island in March for a tour with Royke Mananta, the founder and director of Explore Iso Indonesia. Mananta arranged for an extension of the trip at a site run by local guide Zeth Wonggor and his family. The location was only recently made accessible by the construction of a new road.

Hoops found the Broad-billed Fairywrens just 200 meters from camp. He recorded their faint calls on his phone and uploaded the audio to eBird, then returned the next day with his camera. On the second search, he found two fairywrens and attempted to photograph them — but the tiny, quick-moving birds proved a difficult subject to capture. Eventually, he got what he deemed “the world’s worst picture,” a blur of a bird, along with additional sound recordings. He omitted the photo in his initial eBird observation, adding it later when a reviewer from the platform requested further evidence of the sighting.

Less-than-perfect documentation of a lost species can sometimes generate uncertainty. A few seconds of blurry video taken in Arkansas in 2004 famously sparked years of debate about whether the clip verified the existence of the Ivory-billed Woodpecker. In the fairywren’s case, however, the fuzzy image, quiet notes, and geographic location of the sighting definitively rule out any confusion species. “The structure, pitch, and speed of delivery sound quite similar to the closely related Campbell’s Fairywren [which only occurs in southern New Guinea], and those blue blurs look good for the color zones,” explains ornithologist Iain Woxvold, an expert on New Guinea birds who recently described a new species from the island. “Taken together, I can’t think of anything else that could produce that combination of sound and color.”

Unlike many species on the lost birds list, the Broad-billed Fairywren is not in danger of extinction — classified as Least Concern by the IUCN Red List in 2024 — and presents no taxonomic controversy. Still, many aspects of the bird’s ecology remain unknown. Limited surveys in the fairywren’s range, combined with its elusive behavior, have left researchers with little documentation and a gap in knowledge. Hoops’ contribution, though imperfect, adds meaningful data to the scientific record.

“Documentation doesn’t need to be flawless to be valuable. Every record matters. And each observation can have a ripple effect, encouraging others to find and document the rediscovered species,” says John Mittermeier, director of the Search for Lost Birds at American Bird Conservancy.

The Broad-billed Fairywren is not the only lost bird that Hoops has searched for on his travels. Twice in the highlands of New Guinea, he thought he glimpsed the Archbold's Owlet-nightjar, a species lost to science for more than four decades. He also journeyed to the interior of the island of Espiritu Santo in Vanuatu to find the Mountain Starling, last documented 34 years ago. His group were sure they spotted the starling but left without a photograph. “One guy went off chasing it through the forest, and he still didn’t get a photo,” Hoops says.

As the Search for Lost Birds continues — and as cameras and audio recorders become increasingly accessible — the potential to rediscover species like Archbold’s Owlet-nightjar and Mountain Starling feels closer than ever. Hopefully it is only a matter of time before someone captures proof of their continued survival.

Nina Foster is a science communication specialist with interests in ornithology, forest ecology, and sustainable agriculture. She holds a BA in English literature with a minor in integrative biology from Harvard University and is currently an environmental educator at Schoodic Institute at Acadia National Park.

Support The Search for Lost Birds

Donations from supporters like you make expeditions, science, and conservation possible. Help support the Search.