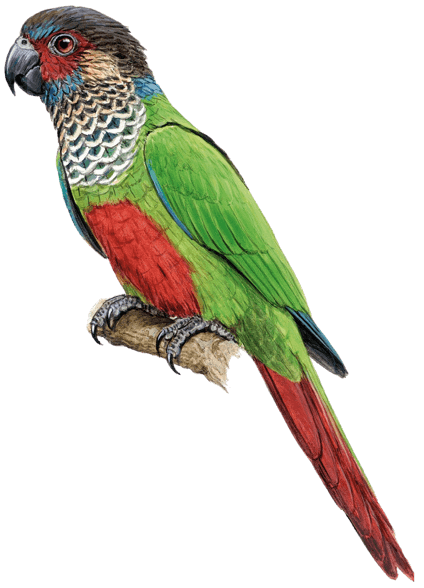

Sinú Parakeet

Pyrrhura subandinaFAMILY

New World and African Parrots (Psittacidae)

LAST DOCUMENTED

1949

(77 years)

REGION

South America

IUCN STATUS

Critically Endangered (Possibly Extinct)

Last Documented

The last specimen is from Cerro Murrucucú in northwestern Colombia (June 1949).

Page Editors

- Search for Lost Birds

Species News

New Evidence and Advances in the Search for the Sinú Parakeet

John C. Mittermeier / 28 Apr 2025

Read MoreOn September 7, 2024, Samuel Doria, a local resident from the municipality of Valencia, Córdoba, Colombia, contacted the team at Sociedad Ornitológica de Córdoba (SOC) to share some news: A parakeet that looked like the Sinú Parakeet had been seen in the village of El Cairo, a rural area of Valencia. Samuel also had a photograph of the bird that he took with his cell phone. Although the image was not high quality, it showed the silhouette of a parakeet with a dark spot on its abdomen, a feature that sparked a lot of interest.

This report marked the beginning of a new phase of the search for the Sinú Parakeet. I was appointed to lead the search, and on September 25, 2024, I conducted an initial five-day expedition to investigate the area where the bird was spotted. This first expedition to Valencia did not find the Sinú Parakeet, but concluded that more time and effort were needed to explore the remnants of forest in this area, which had never had an ornithological survey.

Valencia is located in the sub-region of Alto Sinú, in the western part of the department of Córdoba, in the foothills of the Serranía de Abibe, a spur of the Cordillera Occidental. It is a transition zone between the humid and tropical Andean and Caribbean ecosystems, making it a region extremely rich in biodiversity.

Biogeographically, this area is part of the Greater Colombian Caribbean and is influenced by the Chocó and the Magdalena Valley, which generates a unique ecology. Its forests are connected to the Paramillo National Natural Park and the rural areas of Montería through the Sinú River, areas where the Sinú Parakeet was historically reported between 1909 and 1949.

The Sinú Parakeet: History, Current Status, and Search Efforts

SOC, with the support of American Bird Conservancy and the Search for Lost Birds, has led important efforts over the past few years to search for the Sinú Parakeet (Pyrrhura subandina), one of Colombia's most endangered birds and the country’s last remaining lost bird species. The last confirmed record of the parakeet was in 1949, based on specimens collected in the middle and upper Sinú River valley. Since then, there have been no verified sightings despite multiple scientific efforts, which has led to the parakeet being listed as "Critically Endangered (CR) (possibly extinct)" by the IUCN.

That said, there are areas in the Alto Sinú that are difficult to reach and appear to still have potentially suitable habitat. As a result, SOC has kept searching for the parakeet, combining scientific expeditions with community work and environmental education including posters that have reached every corner of southern Córdoba. Although no recent sightings have been confirmed, this work has increased scientific knowledge about the region’s biodiversity and helped identify priority areas for conservation like the La Cristalina reserve.

Throughout the expeditions we have met strategic partners and allies such as Samuel Doria, his family, and Luis Carlos Martínez in Valencia, who on the recent visits supported us by contacting the owners of nearby farms to facilitate access permits. Their help was fundamental, especially considering the social challenges that often hinder exploration and limit scientific activities in the region.

From February 4 to 25, 2025, we did an additional expedition to Valencia, concentrating our searches in forested areas along the Sinú River. We visited the towns of El Cairo, Río Nuevo, and La Cooperativa, with the support of the Barú Natural Reserve and farms such as Troya, Asturias, Agro Viveros Bosques del Sinú, and Los Bongos.

Vegetation in these areas consisted mainly of grasslands with scattered trees, although places such as Jaraguay Creek and the Barú Reserve had dense and extensive secondary forest, identified as tropical dry forest. During the fieldwork, we recorded 160 species of birds, including parrots such as Orange-chinned Parakeet (Brotogeris jugularis), Blue-headed Parrot (Pionus menstruus), Yellow-crowned Amazon (Amazona ochrocephala), Mealy Amazon (Amazona farinosa), Orange-winged Amazon (Amazona amazonica), Spectacled Parrotlet (Forpus conspicillatus), Brown-throated Parakeet (Eupsittula pertinax), and three species of macaws: Blue-and-yellow Macaw (Ara ararauna), Chestnut-fronted Macaw (Ara severus), and Scarlet Macaw (Ara macao).

We also observed nesting Jabiru (Jabiru mycteria) and migratory bird species. We shared the records with the communities and they were interested in participating and supporting our search.

During the first 14 days we distributed 120 posters that said "Wanted: the Sinú Parakeet alive and free" among farmers and members of local communities. The local community was enthusiastic, but ultimately no one saw any signs of the parakeet. The severe drought, typical in the summer, also reduced the availability of food for the birds, which may have affected the presence of the species in the area.

We decided to postpone our next search until the rainy season. The rains stimulate flowering and leaf growth in deciduous trees such as roble rosado (Tabebuia rosea), roble amarillo (Handroanthus chrysanthus), totumo (Crescentia cujete), guayacán (Bulnesia arborea), matarratón (gliricidia sepium), and ceibo (Erythrina fusca), species that offer nectar, fruits, and flowers attractive to psittacines. We were also encouraged to extend our search to more forested areas of the Serranía de Abibe.

Local Accounts of Historic Sinú Parakeet Sightings

During the second expedition, we visited the village of Nicaragua. There we met Leider Correa and his wife, who were returning from fishing. When we talked about our project, Leider surprised us by saying, "You are looking for the Sinú Parakeet, right?"

With emotion, he recounted that between 1990 and 1992, when he was a student, his teacher Carlos Díaz organized birdwatching trips to raise awareness among the students against hunting with slingshots. On one of those outings they found a pair of very colorful parakeets that they identified as Sinú Parakeets. Professor Díaz taught them about the species, and showed them his field notes and a photograph of a pair of captive Sinú Parakeets that he had managed to take during a visit to the Alto Sinú. The professor died more than 20 years ago, but if this photo can be found, it would be the only definite photograph ever taken of the parakeet and the most recent record of species, radically moving up the date of its last documentation. Beyond its historical value, this photograph could be a key piece in understanding the presence of the Sinú Parakeet in the wild during Colombia’s armed conflict, when scientific research in the area was practically impossible. The simple fact that a rural teacher dedicated part of his life to teaching his students about the importance of this bird, and possibly documenting its presence, could help searchers rediscover the species.

Leider said that the teacher used to say that "that bird should be on the department's coat of arms" because it was unique to Córdoba. Unfortunately, Professor Diaz was a victim of the armed conflict. Luis Carlos, with his characteristic enthusiasm, set out to find the teacher's family in the hope of recovering the photograph or his old teacher’s notes.

Thanks to Leider's directions, we were able to visit the El Congreso farm in the Matamoros trail, the most remote area we visited on the Serranía de Abibe. Although we only stayed five days, between Nicaragua and Matamoros we were able to record 152 species of birds. The tracts of forest were larger, and flocks of parrots and macaws flew among trees blooming from the first rains. We were left with the feeling that this was the right place, but time had run out.

Next Steps and Conservation Prospects

Even though we have not yet found the Sinú Parakeet, our efforts have been far from fruitless. The results so far have provided us with valuable information that gives us a clearer route to continue our search. Between the two expeditions, we recorded a total of 195 bird species in the area, including multiple species of psittacine, suggesting that the habitat is still favorable for birds like the Sinú Parakeet. The next step in our mission is to find Professor Carlos Díaz's photograph, a possible photographic record of the species from three decades ago. This could help us to better understand the more recent presence of the parakeet in the region and provide a key piece to our research.

Beyond the search for photographs, surveys must continue in the extensive Serranía de Abibe forests and the areas surrounding the Sinú River. These areas are still underexplored and could hide the last populations of Sinú Parakeet. In addition, collaboration with local communities remains crucial, as they are the main allies in this mission. Continuing to publicize the search is also vital to maintain interest and raise awareness about the importance of the parakeet not only for conservation but also for culture in the department, so that we can involve local communities more and more in the protection of our natural heritage. Although the road remains challenging, there is much to explore and we are more committed than ever to rediscovering the Sinú Parakeet.

Eduar Páez is a biologist and ornithologist who has worked with SOC since it was founded. He has actively participated in multiple expeditions searching for the Sinú Parakeet, and supports conservation projects focused on endangered bird species, education, community science, and responsible birdwatching.

This fieldwork was supported by a grant from American Bird Conservancy through the Search for Lost Birds.

En Español:

Búsqueda del Lorito del Sinú en Valencia, Córdoba: Nuevos Indicios y Avances

El 7 de septiembre de 2024, Samuel Doria, habitante del municipio de Valencia, Córdoba, se comunicó con el equipo de la Sociedad Ornitológica de Córdoba (SOC) para compartir un reporte: en la vereda El Cairo, zona rural de Valencia, se observó una cotorra con características similares al Lorito del Sinú. Samuel acompañó el reporte con una fotografía tomada con su celular. Aunque la imagen no tenía buena calidad, permitía ver la silueta de una cotorra con una mancha oscura en el abdomen, un rasgo que despertó mucho interés.

Este indicio marcó el inicio de una nueva fase de búsqueda. El biólogo Eduar Páez fue designado para esta tarea y, el 25 de septiembre de 2024, realizó una primera visita exploratoria de cinco días. La expedición concluyó que era necesario invertir más tiempo y esfuerzo para explorar los remanentes de bosque de esa zona, la cual no contaba con información previa sobre su Avifauna.

Valencia, se encuentra ubicada en la subregión del Alto Sinú, al occidente del departamento de Córdoba, en el piedemonte de la Serranía de Abibe, una estribación de la Cordillera Occidental. Esta posición le otorga un valor estratégico como zona de transición entre ecosistemas andinos, húmedos tropicales y caribeños, convirtiéndola en una región de extraordinaria riqueza ecológica y paisajística.

Biogeográficamente, hace parte del Gran Caribe Colombiano y presenta influencia del Chocó biogeográfico y del valle del Magdalena, lo que genera un mosaico ecológico único. Sus bosques se conectan con el Parque Nacional Natural Paramillo y con las zonas rurales de Montería a través del río Sinú, áreas donde históricamente se reportó el Lorito del Sinú entre 1909 y 1949.

El Lorito del Sinú: Historia, Estado Actual y Esfuerzos de Búsqueda

La Sociedad Ornitológica de Córdoba (SOC), con el apoyo del programa Search for Lost Birds de American Bird Conservancy, ha liderado importantes esfuerzos para la búsqueda del Lorito del Sinú (Pyrrhura subandina), una de las aves más amenazadas de Colombia. El último registro confirmado de la especie fue en 1949, basado en especímenes recolectados en el valle medio y alto del río Sinú. Desde entonces, no han habido avistamientos verificados a pesar de numerosos esfuerzos científicos, lo que ha llevado a catalogarla como “En Peligro Crítico (CR) (posiblemente extinta)” por la UICN.

Aun así, existen zonas de difícil acceso en el Alto Sinú con hábitats potencialmente adecuados. Por esta razón, la SOC ha persistido en la búsqueda, combinando expediciones científicas con trabajo comunitario y educación ambiental mediante afiches de la especie que han llegado a todos los rincones del sur de Córdoba. Aunque no se han confirmado avistamientos recientes, estas expediciones han fortalecido el conocimiento sobre la biodiversidad regional e identificado áreas prioritarias para la conservación.

Durante todas las expediciones realizadas hemos conocido socios y aliados estratégicos como Samuel Doria, su familia, y Luis Carlos Martínez en Valencia, quienes nos apoyaron contactando a los propietarios de fincas cercanas para facilitar los permisos de acceso. Su ayuda fue fundamental, especialmente considerando los retos sociales y de orden público que a menudo dificultan la movilidad y limitan las actividades científicas en la región.

Del 4 al 25 de febrero de 2025, concentramos la búsqueda en zonas boscosas cercanas al río Sinú. Visitamos las localidades de El Cairo, Río Nuevo y La Cooperativa, con el apoyo de la Reserva Natural Barú y fincas como Troya, Asturias, Agro Viveros Bosques del Sinú y Los Bongos.

La vegetación en estas áreas consistía principalmente en pastizales con árboles dispersos, aunque lugares como la quebrada Jaraguay y la reserva Barú presentaban bosque secundario denso y extenso, identificado como bosque seco tropical. Durante este período registramos 160 especies de aves, incluyendo diez especies de psitácidos como el periquito alibronceado (Brotogeris jugularis), el loro cabeza azul (Pionus menstruus), el loro real amazónico (Amazona ochrocephala), el loro harinoso (Amazona farinosa), el loro alinaranja (Amazona amazonica), el periquito de anteojos (Forpus conspicillatus), el perico cariamarillo (Eupsittula pertinax), y tres especies de guacamayas: azul y amarilla (Ara ararauna), severa (Ara severus) y bandera (Ara macao).

También observamos la anidación del Jabirú (Jabiru mycteria) y la presencia de diez especies migratorias. La socialización de estos registros con las comunidades despertó su interés por participar y apoyar la búsqueda.

Durante los primeros 14 días repartimos 120 afiches de la campaña “Se busca el lorito del Sinú vivo y en libertad” entre campesinos y miembros de comunidades locales. A pesar del entusiasmo, el panorama fue retador: había desconocimiento sobre las aves locales y nadie logró identificar al lorito. La fuerte sequía, típica de la época de verano, también redujo la disponibilidad de alimento para las aves, lo que pudo afectar la presencia de especies en la zona.

Se propuso una pausa para sincronizar la siguiente salida con el inicio de las lluvias. Estas lluvias estimulan la floración y el crecimiento de hojas en árboles caducifolios como el roble rosado (Tabebuia rosea), el roble amarillo (Handroanthus chrysanthus), el totumo (Crescentia cujete), el guayacán (Bulnesia arborea), matarratón (gliricidia sepium) y el ceibo (Erythrina fusca), especies que ofrecen néctar, frutos y flores atractivos para psitácidos. También nos recomendaron extender la búsqueda hacia áreas más boscosas de la Serranía de Abibe.

Testimonio Local Sobre Avistamientos Históricos del Lorito del Sinú

Durante la segunda etapa, visitamos la vereda Nicaragua. Allí conocimos a Leider Correa y a su esposa, quienes regresaban de pescar. Al conversar sobre nuestra búsqueda, Leider nos sorprendió diciendo: “¿Ustedes están buscando el Lorito del Sinú, cierto?”

Con emoción, relató que entre 1990 y 1992, cuando estudiaba en la escuela mixta de Nicaragua, su maestro Carlos Díaz organizó jornadas de observación de aves para concientizar a los estudiantes sobre la caza con cauchera. En una de esas salidas encontraron una pareja de cotorras muy coloridas que identificaron como Loritos del Sinú, el profesor Díaz les enseñó sobre la especie, además de sus notas de campo y mostró una fotografía de una pareja de Lorito del Sinú en cautiverio que había logrado tomar en una visita al Alto Sinú; el profesor murió hace más de 20 años y con él su historia, si esta imagen llegara a encontrarse, representaría el registro visual más reciente de la especie con al menos 32 años, lo cual cambiaría radicalmente la línea de tiempo conocida para la especie. Más allá de su valor histórico, esta fotografía podría convertirse en una pieza clave para entender la presencia del Lorito del Sinú en vida silvestre durante las décadas del conflicto armado, cuando la investigación científica en la zona era prácticamente imposible. El simple hecho de que un maestro rural haya dedicado parte de su vida a enseñar a sus estudiantes sobre la importancia de esta ave —y posiblemente haya documentado su presencia— le devuelve al Lorito del Sinú una parte de su historia olvidada.

Leider relató que el maestro decía que “esa ave debería estar en el escudo del departamento” por ser única. Lamentablemente, el profesor fue víctima del conflicto armado. Luis Carlos, con su entusiasmo característico, se propuso buscar a la familia del profesor con la esperanza de recuperar la fotografía o sus bitácoras.

Gracias a las indicaciones de Leider, logramos visitar la finca El Congreso en la vereda Matamoros, el punto más remoto que alcanzamos sobre la Serranía de Abibe. Aunque solo estuvimos 5 días, entre Nicaragua y Matamoros logramos registrar 152 especies de aves. Los relictos de bosque eran más extensos, y las bandadas de loros y guacamayas volaban entre árboles florecidos por las primeras lluvias. Nos quedó la sensación de que ese era el sitio indicado, pero el tiempo se había agotado.

Próximos Pasos y Perspectivas de Conservación

Aunque no hemos encontrado aún al Lorito del Sinú, nuestra exploración no ha sido para nada infructuosa. Los resultados obtenidos hasta ahora nos han proporcionado valiosa información que nos traza una ruta más clara para continuar la búsqueda. Hemos registrado un total de 195 especies de aves en la zona, incluyendo diversas especies de psitácidos que sugieren que el hábitat sigue siendo favorable para especies como el Lorito del Sinú. El siguiente paso en nuestra misión es encontrar la fotografía del profesor Carlos Díaz, un posible registro visual de la especie de hace tres décadas. Este hallazgo podría ayudarnos a comprender mejor la presencia del Lorito en la región durante los años más recientes y aportar una pieza clave a nuestra investigación.

Más allá de la búsqueda de la fotografía, la exploración debe continuar en los extensos bosques de la Serranía de Abibe y las zonas aledañas al río Sinú. Estas áreas, aún siguen inexploradas por completo y podrían ocultar las últimas poblaciones de esta especie emblemática. Además, la colaboración con las comunidades locales sigue siendo crucial, ya que ellos son los principales aliados en esta misión. La continuación de la divulgación de la búsqueda es también vital para mantener el interés y generar conciencia sobre la importancia del Lorito del Sinú no solo para la conservación sino también para la cultura en el departamento, involucrando cada vez más a la sociedad en la protección de este tesoro natural. Aunque el camino sigue siendo desafiante, hay mucho por explorar y estamos más comprometidos que nunca con esta noble causa.

Eduar Páez es biólogo y ornitólogo vinculado a la Sociedad Ornitológica de Córdoba (SOC) desde sus inicios; ha participado activamente en exploraciones y expediciones de búsqueda del Lorito del Sinú (Pyrrhura subandina), además, ha promovido procesos de conservación de especies de aves amenazadas, educación, ciencia comunitaria y aviturismo responsable.

Este trabajo fue financiado por American Bird Conservancy a través del proyecto Search for Lost Birds.

After years of conflict, might a lost parakeet species reveal itself in this Colombian forest?

Cameron Rutt / 26 Jun 2023

Read MoreThis week in northwestern Colombia, a team of researchers is searching for the Sinú Parakeet (Pyrrhura subandina), a species that has not been officially documented in more than 70 years. After decades of violent civil conflict, one of the many benefits of peace in Colombia has been the chance to discover if, after all these years, this endemic species remains hidden in the country's threatened yet under-explored forests.

Located on Colombia's Caribbean coast, most of the department of Córdoba is made up of lowlands under 330 feet (100 meters) in elevation. Named for the river that bisects the department, the Sinú Parakeet was last documented in 1949, in the dry forests of the country's foothills. Since then, cattle ranching, farming, and illegal logging have all taken a toll on this forest: “Ninety percent of the dry forest has disappeared,” according to Hugo Herrera Gomez, President of Sociedad Ornitológica de Córdoba.

Once believed a subspecies of the Painted Parakeet (Pyrrhura picta), the Sinú Parakeet was only recently recognized as a separate species, many decades after the last individual was seen alive. As a result, very little is known about its reproduction, nutritional requirements, ecology, or behavior. Moreover, Colombia's civil conflict (which officially ended with a 2016 peace deal between the government and FARC) disrupted research in the country's forests for decades, making it impossible to find out if the parakeet still inhabits them. Some local farmers have described seeing a bird with similar characteristics in recent years, but no hard evidence has surfaced proving that the bird has been found.

This expedition seeks to remedy that. “It's a species that is unique to the department, unique to the country, and unique to the world,” says Herrera Gomez. “Something has to be done to protect the species, if it is still out there.”

The expedition

In late February, a team of 14 biologists and local residents, including those who may have spotted the parakeet, will embark on a 10-day expedition to search for the bird, which is one of Global Wildlife Conservation's 25 “most wanted” lost species. The search, which Herrera Gomez calls “a dream come true,” is a collaboration between Sociedad Ornitológica de Córdoba, Asociación Calidris, and Colombia's national park authority, with support from Global Wildlife Conservation and American Bird Conservancy. Herrera Gomez also stresses that without the enthusiasm and support of the nearby communities, this expedition would not be possible. The local organizations supporting the expedition include Urra SA ESP, Vortex Colombia, Colombia Birding, Café de Cordoba, and Urabá Nature Tours.

The team will search the relatively well-preserved highland forest around Alto Sinú, where the last parakeet sightings were reported in 1949. While this area is known to be important habitat for other endemic and endangered birds, including the Blue-billed Curassow and the Chestnut-winged Chachalaca, there has never been a complete ornithological study conducted there, although there were expeditions mounted to search for the Sinú Parakeet between 2004 and 2005, by Fundación ProAves. In Alto Sinú, there is basically no recorded data from altitudes above 1,300 feet (400 meters). The researchers will split up into small groups and walk transects through the forest, noting the species they observe and listening for vocalizations. They will then upload the lists of avian species they record to eBird, a popular tool for scientists and birdwatchers that is managed by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

What will they find?

Herrera Gomez is optimistic that the team will find the Sinú Parakeet, citing other rare and “lost” parakeet species. In 1999, a group of researchers sponsored by American Bird Conservancy and Loro Parque Fundación found the rare Yellow-eared Parrot. Before its re-emergence, ornithologists were wondering if the species had been lost. Then, a decade after researchers found 81 of the parrots high in the Colombian Andes, a second population was found in foothill forests. The Perijá Parakeet and Indigo-winged Parrot were also both once lost to science. The Indigo-winged Parrot was rediscovered as recently as 2002 after decades of civil conflict prevented scientific surveys from being conducted. Herrera Gomez's bigger concern is that if the Sinú Parakeet still exists, its population is likely quite small, which will make it harder to find.

No matter what the expedition finds, it will undoubtedly be a step forward for science. “Because this area has not been well studied before, even if they don't find the parakeet, [they] will have lots of new info they can bring back from the field,” Herrera Gomez says. “Anything new will be interesting.”

An expedition for a lost bird finds dozens of other species thriving in a dense Colombian forest

Cameron Rutt / 5 Jul 2023

Read MoreNearly 2,300 feet straight up. That was the climb an expedition team faced in the Murrucucú mountains in Alto Sinú in Colombia’s department of Córdoba to reach their base camp. Local guides sometimes had to carve out steps for the rest of the team to scramble up the mountain side. For stretches, the mountainside was so steep the expedition team used ropes to pull themselves up. But the climb was well worth it.

Every morning for 10 days in late February and early March 2021, 10 members of the expedition team climbed from the base camp to a plateau with low premontane tropical forest on the northern slope of the Murrucucú in hopes of finding the Sinú Parakeet. The small green, red and blue parakeet is one of Re:wild’s top 25 most wanted lost species. There hasn’t been a confirmed sighting of the avian mountain-dweller since 1949, but the Murrucucú mountains are largely unexplored and could have been hiding the parakeet as well as other species.“The avifauna up there was absolutely strikingly different,” says Diego Calderón-Franco, an ornithologist leading the expedition.

Until the expedition to find the Sinú Parakeet, which included a team of local naturalists, biologists, university students and rangers from the National Parks Authority, there had never been a complete ornithological survey of Alto Sinú due to Colombia’s decades-long violent civil conflict.

The expedition didn’t find the Sinú Parakeet, but what they did find has made them hopeful that the colorful parakeet may still live in one of the nearby mountain ranges that make up the northern part of the western Andes.“Even though the ecosystem we found has been somewhat disturbed, it's still preserved, supporting many different species,” says Hugo Alejandro Herrera Gómez, president of Sociedad Ornitológica de Córdoba and a leader of the expedition. “Not only does the ecosystem support birds, but also many types of life. I am very hopeful of finding the parakeet in there.”

Local communities around Alto Sinú were a critical part of the initial search and they are helping the effort to document the species in the mountains and continue the search for the Sinú Parakeet. Their local knowledge and enthusiasm for the search largely made it a success.New bird species for Córdoba department

The expedition documented 238 species of birds during their survey. Of those about 22 had never been documented in the department of Córdoba before. The new species means there are now around 589 species of birds known to live in the department. Several of the dozens of new species were found by the local naturalists and guides on the expedition.

The expedition team focused their search on two different types of habitat with plants that they suspected may attract a species like the Sinú Parakeet. They spent hours observing the species of birds that visited fruiting palm trees, fig trees and other fruiting trees.

“We really invested time on those not only because of the parakeet, but because we were also finding new species for Córdoba, in those places,” says Calderón-Franco.

The very first day of the expedition, as the team was ascending to a ridge via a trail carved out of the mountainside by the local guides, Diego Calderón-Franco, the lead biologist caught a glimpse of a Sharpbill. The tiny olive-and-yellow bird is rare. It’s only been seen in Colombia four other times. Calderón-Franco frantically called to the other team members to capture a photo of the bird, but it flew away before anyone else could get in position to see it.“This bird has only been found in Colombia a few times in the San Lucas mountain range in the northern, central Andes, and in the Chocó,” explains Calderón-Franco. “It is one of the rarest birds in the country.”

The team tried desperately to attract the bird by playing callbacks, or recordings of its own calls, in hopes it would respond and return. But it didn’t make another appearance.

Three days later, Johan Arley Villalba Ogaza, a field assistant and a local tour guide with Sinú Travel, was looking through photos he had taken. He asked some team members if they recognized a bird he had photographed just a few minutes earlier while climbing the ridge with the lunches for the expedition team. He showed them the photo on the screen of his camera—it was the Sharpbill. The photo was the definitive proof the expedition needed that the bird they had seen was a Sharpbill and its range included the Murrucucú mountains.Not lost, but as equally elusive

One of the biggest sightings on the expedition practically sneaked up on the team. After a morning of surveying birds not too far from their base camp, they were heading back for lunch and were stopped in their tracks on the trail. Yulisa María Navarro Gandía, a junior researcher with Sociedad Ornitológica de Córdoba, whispered to Calderón-Franco what was causing the hold up: a Correcaminos, also known as a Roadrunner or a Ground-cuckoo.

They only saw the Ground-cuckoo, a ground-dwelling bird with a long tail and a crest on its head, for a few seconds, but that was a few seconds more than most. It’s extremely secretive and difficult for even trained ornithologists to find. Ground-cuckoos follow swarming army ants to pick off prey that escape the swarm. They eat everything from insects to snakes and other small birds.

As the bird scurried off, running along the forest floor, the team could hear it’s telltale bill-snap. The glimpse was not enough to determine exactly what species of Ground-Cuckoo the team saw—there are four species of ground-cuckoos in Colombia and a couple of those could possibly be found in the Murrucucú—but it was enough to elicit a thrill.Curious squirrels

The Murrucucú were not only bustling with birds, the team also found many species of mammals. They saw sloths, monkeys and kinkajous to name a few.

One mammal stopped them in their tracks. It was a dwarf squirrel with white ears. The squirrel didn’t match the description of any known species and the expedition team thinks it may be new to science, though they need more evidence to confirm it.

A sensational snake

Though birds and the Sinú Parakeet were the main objective for the expedition, Carlos Mario Bran-Castrillón and Willian Alexander Brand-Castrillón, the expedition’s herpetologists, were also searching for amphibians and reptiles. Their curiosity about and affection for snakes and amphibians infected the entire expedition team.

“The second snake we encountered was a species I had wanted to see for many years. Seeing it on a field trip was very nice,” said Carlos Mario Bran-Castrillón. “The frog species were also fascinating, particularly the glass frogs we encountered at the end of the excursion.”

The expedition’s rarest snake find was a Chocoan Lancehead. The snake is so rare, not even the herpetologists had seen one in the wild before. Chocoan Lancehead snakes are venomous snakes with beautiful brown square patterns. They spend much of their time camouflaged on the forest floor, or not far from it, waiting to ambush prey that wander within striking distance of their hiding places. The females give birth to live young, hatching clutches of eggs inside their bodies.“Having experts in herpetology in the expedition was a plus,” says Eduar Luiz Páez Núñez, a junior researcher with Sociedad Ornitológica de Cordóba. “It was very productive to learn about Alto Sinú amphibians and snakes. The Bothrops punctatus [Chocoan Lancehead] was one of the species that drew the most attention for its color pattern and dangerousness.”

Amazing amphibians

The amphibians of the Murrucucú Mountains are as little studied as the birds. One of the frogs the team found was a tiny red frog known as Andinobates victimatus, a species only known from the neighboring Urabá region. It would be the first record of the species in the Murrucucú. The species is named in honor of the victims of the civil conflict that has caused Urabá, and the Murrucucú mountains to be underexplored.

“I didn't expect to see the red frog; furthermore, I didn't even know it existed,” says Enith Martinez Salcedo, the camp cook from Tierralta, a town at the base of the Murrucucú. “It was a huge surprise to see it in person.”Birds of prey

Songbirds and flycatchers weren’t the only types of birds the team saw. The Murrucucú are also home to birds of prey.

“This mountain supports a ton of big raptors,” says Calderón-Franco. “We got Ornate Hawk-eagle, Crested Eagle, Black-and-white Hawk-eagle, Barred Hawk, big animals that are apex predator birds. That also talks about the quality of the habitat there.”

Predators can only thrive in healthy ecosystems that can support them, and members of the expedition team were just as excited about the possibility of seeing them as they were about searching for the Sinú Parakeet.

“I wanted to see several species,” says Herrera Gómez. “Besides the parakeet, I had a list of about 10 species I dreamed of seeing. I remember being most excited about seeing the Ornate Hawk-eagle or Spizaetus ornatus, and it appeared twice. It was spectacular. My dream came true.”

Precocious plants

Although wildlife was the main focus of the expedition, the flora of the Murrucucú is similarly under-studied. Based on some of the plants the team saw, the Murrucucú is home to plants endemic to Colombia.

One tree in particular stopped them in their tracks. The tree had little flowers growing directly out of its trunk, which is unusual. The team couldn’t identify it in the field, but they think it’s likely that it’s in the cocoa family. After consulting with other botanists, they think it may have been only the third time ever that the tree (Theobroma cf. cirmolinae) has been documented in Colombia.

The search continues

Although the expedition team didn’t find the Sinú Parakeet hiding in the Murrucucú, the number of unexpected discoveries they made in the forest has given them hope that the bird may still be there or living in a different underexplored part of Colombia.

“I do have hope and I think it is possible that the parakeet is here in the Paramillo National Park,” says Daniel Alvarado, a field assistant with Parques Nacionales Naturales de Colombia. “We just have to keep looking for it.”

A second expedition, organized by Sociedad Ornitologica de Córdoba and American Bird Conservancy, is hoping to set out sometime in the next year.

Support The Search for Lost Birds

Donations from supporters like you make expeditions, science, and conservation possible. Help support the Search.