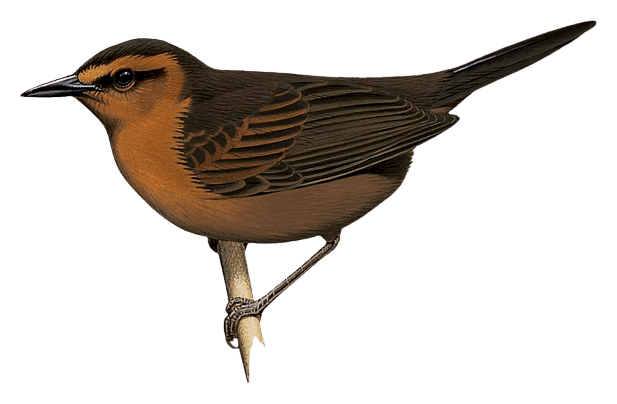

Bougainville Thicketbird

Cincloramphus llaneaeFAMILY

Grassbirds and Allies (Locustellidae)

LAST DOCUMENTED

2002

(24 years)

REGION

Oceania

IUCN STATUS

Near Threatened

Background

Bougainville Thicketbirds are found only in mountain forests on the island of Bougainville, Papua New Guinea, where very little is known about the species. The thicketbird was photographed in spectacular fashion in September 2024 by a group for Ornis Birding Expeditions. Prior to this, the most recent documented records of Bougainville Thicketbirds were published photographs from 2001 and a specimen collected in 2002, meaning that it was lost 22 years between documented records.

Last Documented

The most recent records of the species are photographs taken in 2024 and publicly available on eBird. The last record before 2024 appears to be a specimen at the University of Kansas Biodiversity Institute that was collected on 31 August 2002 in Bougainville's Crown Prince Range. D. Hadden published two photographs of Bougainville Thicketbird in his book Birds and Bird Lore of Bougainville and the North Solomons (Dove Publications, 2004), including one of a juvenile bird found by J. Toroura in September 2001.

Page Editors

- Search for Lost Birds

Species News

FOUND: Two Lost Birds in a week (almost!)

John C. Mittermeier / 29 Nov 2024

Read MoreBougainville: an island few could point to on a map, in the remote southwest corner of the Pacific. It was completely unknown to ornithology until an expedition led by Albert Meek in 1904, and largely neglected since due to challenging access and an extended period of political unrest. Two birds found only on the island, the Bougainville Thicketbird and Bougainville Thrush, were among those counted as lost to science by the Search for Lost Birds (with more than 20 years since the last documented records), and another, the Bougainville subspecies of Moustached Kingfisher, had never been photographed in the wild despite numerous recent searches. That is, until the end of our visit!

Several other birdwatching groups in recent years have visited Bougainville, an autonomous region within Papua New Guinea, though none were successful in finding the rare species.

From 1988 to 1998, Bougainville was embroiled in a bloody conflict (often referred to as the Bougainville Crisis or Civil War) triggered by disputes over mining operations in the island’s mountainous interior. While the political situation is improving, and Bougainville is on track to become an independent country in the next two-to-three years, distrust of outsiders remains high in parts of the island, and people are understandably suspicious of foreign visitors. As a result, accessing the montane forest has been extremely challenging or impossible in many areas. After months of careful planning and communication with local colleagues on Bougainville, I was able to coordinate a rare visit to the island’s mountains in September 2024.

With a keen group of Ornis Birding Expeditions tour participants joining me, we arrived early in September and together with Steven Tamiung, a birding guide from eastern Bougainville, set to work negotiating access to promising areas of forest with local communities and landowners. During the first 10 days we visited several tracts of forest, all of which had clearly been subject to heavy hunting and birds were difficult to find. Often a large, excited group of people would form around us when we pulled out the field guide in a village, pointing at the species we were looking for, which was our best method of assessing the prospective birdlife of an area.

In particular we were hoping to find the Bougainville subspecies of Moustached Kingfisher, a near-mythical bird which had been the main target of recent birding trips to the island. To the ornithological world, this kingfisher is known from a single specimen collected in 1904 along with two reported sightings in the 1900s. A photograph of a dead individual in 2023 and a few scattered reports of birds being heard were the only recent confirmation that this distinctive subspecies still exists. In 2015, a research team from the American Museum of Natural History found several pairs of the Guadalcanal subspecies of Moustached Kingfisher in the neighboring Solomon Islands. They acquired the first-ever sound recordings, which made it possible for us have a real chance at locating the birds on Bougainville.

However, as each day passed, the situation seemed to become increasingly hopeless. Local people would point us to where they thought they had seen the bird, but after a two-hour trek we would discover an area invariably inhabited by one of the other three kingfisher species found here. After interviewing nearly 100 people in the highlands, only three could accurately describe our target and none of them had seen it recently. Nobody we talked to recognized the lost Bougainville Thrush or Bougainville Thicketbird.

Finally, we were granted access to a forested ridge where the landowners assured us was no longer used for hunting, due to the proximity of a new road. As we climbed into the forest, it was quickly apparent that there were more birds here. Feeding flocks of monarchs and white-eyes moved through while dozens of lorikeets and pigeons passed overhead.

The kingfisher is said to only vocalize in the predawn darkness, so early the next morning our intrepid team was spread out along the ridge, listening intently. Twice I heard a very soft noise to my left; maybe a contact call, but maybe a frog. Nevertheless, we focused on this spot and crept down the slope as dawn began to break. We waited for a while, hearing nothing else. We carefully played the song from Guadalcanal, which suddenly prompted a loud and distinctive cackle to echo across the gully in response. Moments later, announced by a loud whoosh, an electric-blue male Moustached Kingfisher flew in and landed just meters from us. Ten seconds later he was gone. After the brief sighting and our disbelief faded, we high-fived.

Despite being darker orange with a slower and more drawn-out song than the Guadalcanal birds, for now the “Bougainville” Moustached Kingfisher remains lumped with birds from Guadalcanal and is thus technically not a lost bird. However, we suspect it will be recognized as a distinct species in the near future. Thankfully both photographs and sound recordings were obtained to help support research efforts, though getting these took a few more mornings of careful fieldcraft in the bird’s territory!

Now our attention turned to the cryptic duo of truly lost birds: Bougainville Thicketbird and Bougainville Thrush. Both these species were described in the 1980s, but since then the birds have only been found once or twice—most recently in 2002 when individuals of both species were caught in researchers’ mist nets.

At our new camp, one local hunter appeared who claimed to know the thrush, quite a distinctive bird with bold black and white markings. Walking us up to a dense gully where he used to see them regularly, we were pleased to see that indeed, the habitat looked perfect. We spent much time here, sitting quietly and slowly walking around, though Zoothera thrushes are always extremely furtive and shy.

After lunch on our second day, as I was walking around the gully I accidentally flushed a bird which subsequently began making a strange trilling song. I guessed it was Bougainville Island-Thrush, a relatively common endemic species that was recently split from the widespread Island Thrush found all across the west Pacific. I recorded the sound before hiding carefully and playing it back. For some time, the bird provided brief glimpses as it moved around in the understory, occasionally singing. Suddenly, it hopped onto a log only two meters in front of my face, almost close enough to touch, and I nearly fell over backwards. It was not a Bougainville Island-Thrush. It was a Bougainville Thicketbird!

This group of seldom-seen skulkers, which range from Timor to Fiji, can nonetheless be extremely inquisitive, and the Bougainville Thicketbird was no exception. After I had run down the mountain to find everybody else, we were treated to an absolutely amazing encounter with this lost bird as it walked circles around us. Like with the kingfisher, now having a sound recording proved key. During the coming days we would find a total of five territories, and obtain the first photos of the bird in its natural habitat.

Birding here was excellent. We were constantly entertained by the full suite of more common but nonetheless poorly-known highland endemics of the island. However, much of our time was spent creeping around in steep ravines or lush vegetation, hoping to encounter the remaining lost bird—the Bougainville Thrush. It wasn’t until our last evening at the camp that my colleague and co-leader, Julien Mazenauer, heard a sweet musical tune, of course emanating from the exact same gully we had been focusing on all week!

He recorded the song, but despite searching at night with thermal scopes and attempting one last dawn vigil at the spot, we never got our eyes on this bird. Based on the behavior and comparisons with related Zoothera species, we are almost certain that this was a Bougainville Thrush, but erring on the side of caution it may be best to wait until someone has unequivocal proof in the form of a photo or seeing the thrush singing before officially designating this a ‘found’ bird. Not quite a perfect finish, but a spectacular result nonetheless.

With these new sightings and sound recordings, hopefully future visitors will be able to better search for all the species found on Bougainville and stop them from becoming lost again! After our visit, the community leaders in Guava, where we had been, showed real enthusiasm, celebrating our departure with a ceremony where we gratefully thanked them for allowing us into their forest. Since our visit, a small ecotourism project has been set up to help coordinate cooperation between the landowners here, and several independent birdwatchers have already begun arranging their own trips to visit this exciting Melanesian island.

Joshua Bergmark is the director of Ornis Birding Expeditions, a company which specializes in taking birders to the most challenging destinations on the planet. In the last 12 months, he has led several tours which between them recorded six once lost birds and almost a dozen nearly-lost birds! To learn more about Josh’s recent trip to Bougainville, see the birding trip report.

Support The Search for Lost Birds

Donations from supporters like you make expeditions, science, and conservation possible. Help support the Search.