Slender-billed Curlew

Numenius tenuirostrisFAMILY

Sandpipers and Allies (Scolopacidae)

LAST DOCUMENTED

1994

(32 years)

REGION

Africa

IUCN STATUS

Critically Endangered

Background

This elegant shorebird once bred in central Asia and southern Siberia and spent the winter in wetlands around the Mediterranean and Arabian peninsula. The species was last documented in 1995 at Merja Zerga wetlands in Morocco. In 2024, a thorough review of the status of the Slender-billed Curlew determined that it is extinct. The Slender-billed Curlew is the first documented extinction of a bird species from mainland Europe, and one of the first species of the list of lost birds to be declared extinct. For videos of the last Slender-Billed Curlews at Merja Zerga, click here.

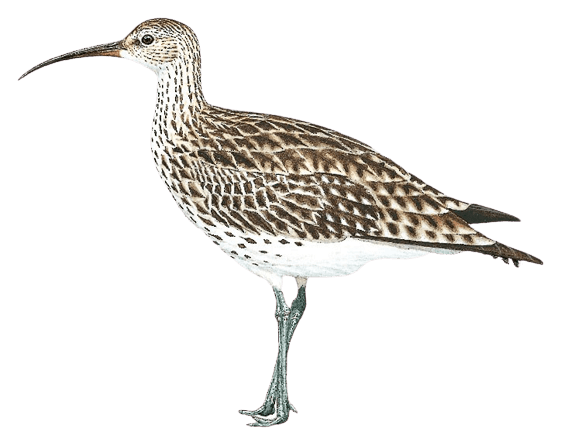

The Slender-billed Curlew was a pale shorebird with a slim, decurved bill and mottled gray-brown plumage. Adults were similar in size to godwits, such as Black-tailed Godwit, weighing up to 360 grams. Similarities in shape and plumage occasionally made Slender-billed Curlews difficult to differentiate from larger, but similarly-patterned, Eurasian Whimbrels (Numenius phaeopus) and Eurasian Curlews (Numenius arquata).

Little is known about the Slender-billed Curlew's breeding behavior and it is, and now that is extinct will remain, the only bird in the Western Palearctic with unknown breeding grounds (Gretton et al., 2002). Nesting pairs were observed in peat bogs with some small willow and birch trees in 1914-1924 near Tara in the valley of the Irtysh River in western Siberia. Nests were in dense growth on dry areas within bogs made of dry grass and in shallow hollows as well as in bog forest transition zones on the northern limit of the forest-steppe zone in taiga marsh habitat (if this is a specialized breeding habitat requirement, this may explain how habitat loss explains the species' decline in the 20th century). However, it is unclear whether the records for the breeding range were taken in the typical habitat of the species or at the limit of the species' range (Galo-Orsi and Boere, 2001), and analyses of stable isotopes in feather samples from museum specimens suggest that the main breeding area was located further south in the steppes of northern Kazakhstan and south-central Russia (IUCN Red List). Some have proposed that there might be breeding grounds in Iran but no evidence has been found to prove this theory, while other potential breeding areas might have existed north of the Caspian Sea between the Volga and Ural rivers. No nesting records since 1925 with the species already in decline in Momsk by the first decade of the 20th century (Birds of the World).

In winter and migration, Slender-billed Curlews visited coastal bays and lagoons with saltmarshes and temporary inland marshes. The last Slender-Billed Curlews seen in Morocco were on the seashore in saline and brackish lagoons, estuaries, temporary and permanent lakes with adjoining marshes, mudflats, and arable fields. According to sightings in Morocco, Slender-Billed Curlews stayed on their wintering grounds mainly between November and March with the first birds arriving in late August and early September with the last departing by mid-May. In migration the curlews passed through central and eastern Europe with a possible second migration route for the specie going through the Middle East to wintering sites in Iraq, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Oman, and Yemen. It is thought by some that this species formerly wintered in the Netherlands (Zuiderzee) through Turkmenistan, the Caspian steppes, Ukraine, and Bulgaria (in these areas they were recorded in the Spring between March 20-May 18 and in the Fall from September 19-November 9). There have even been unconfirmed records of the Slender-Billed Curlew further east in coastal Pakistan and northwest India. Other vagrant records of Slender-billed Curlew include possible reports from the Azores (where two were seen in March 1979 and January 1981), Canada (1 seen in 1925, though this record has been questioned), and Japan (where one was seen in Honshu).

Much of what we know about the Slender-Billed Curlew comes from observations from Merja Zerga. Here, the Slender-Billed Curlews foraged in agricultural fields (December-January) and in wet saltmarshes (January-February). They ate earthworms and tipulid larvae in wet, grazed saltmarshes as well as annelids, mollusks and insects. They used tidal mudflats as roosting sites as they hid among large flocks of waders (Van der Halve et al., 1998)

The call of this species is similar to a Eurasian Curlew but higher-pitched, shorter, and more repeated (cour-lee) that was sometimes followed by 5-7 short ti-ti-ti notes that sound like a laughing trill. On the breeding grounds, birds reported gave a vibrating whistle or loud high-pitched be-be-be-be to mob intruders in breeding territories (Birds of the World)

To listen to recordings of the Slender-Billed Curlew, click here.

Even though numerous surveys in many countries (from the steppes of Kazakhstan to the marshes of Tunisia) since 1995 have found little traces of the Slender-Billed Curlew, the search led to many wetlands across Europe and the Middle East receiving protection. Some of them even have no-hunting zones. Thanks to this species, millions of shorebirds can rely on certain sites to rest and feed during migration and the winter. This is perhaps the bird’s greatest legacy.

For a more detailed overview of the Slender-billed Curlew see Birds of the World.

Conservation Status

For the time being, the Slender-Billed Curlew remains listed as Critically Endangered by the Red List of Threatened Species following the assessment of the species made in 2018 (IUCN Red List). Following the recent study by Buchanan et al. (2024), however, it will likely be recategorized as Extinct in the next Red List update.

Past Conservation Actions

In 1994, the Convention on Migratory Species produced a Memorandum of Understanding regarding the Slender-Billed Curlew (also known as the Bonn Convention). Between the years 1994-2000, a total of 18 countries signed the Bonn Convention. The Bonn Convention stemmed an action plan among the signatories. This Action Plan for the Conservation of the Slender-Billed Curlew was put into effect in July 1994. The goals of this plan included imposing hunting bans and non-hunting zones to protect the Slender-Billed Curlew and lookalike species, creating educational and public awareness programs, protecting key sites, and supporting ornithological surveys seeking to monitor migratory birds in their passage and wintering sites.

Under the Bonn Convention, a Slender-Billed Curlew Working Group was established in 1997. It was relaunched in 2008 with cooperation from 19 countries within the species’ range after the Conference of the Parties of the Convention on Migratory Species (CMS) for that year. The goal of this working group is to record and disseminate data regarding this bird for the purposes of the species’ preservation.

A new action plan for the Slender-Billed Curlew was launched in 2002. This time the goal was to protect the species across all of the 33 countries that encompassed the potential breeding and non-breeding range of the species. This action plan remains in effect with both signatories of the Bonn Convention and other countries within the Slender-Billed Curlew’s range participating in various ways. The plan includes actions to: 1) promote policies that protect the Slender-Billed Curlew; 2) protect the wintering and breeding grounds of this species; 3) monitor threats from hunting; 4) discover new areas of habitat; 5) raise public awareness; 6) train birdwatchers and ornithologists in identifying the Slender-Billed Curlew from other species of shorebird. The action plan also details 20 potential threats to the Slender-Billed Curlew and its habitat (all of which have intensified in recent years) including unsustainable exploitation, drainage of wetlands, and agricultural expansion, among others. For details on the plan, see Galo-Orsi et al. (2002).

Last Documented

The last definitive image of this species appears to be a bird photographed on its non-breeding grounds in coastal Morocco (February 1995; Figure 396 in Kirwan et al. 2015).

The Slender-Billed Curlew was first described in 1817 by L.J.P Vieillot who looked at a specimen collected in Egypt before 1797. Since then, little is known about the species. This is ironic given the fact that the bird wintered often in Europe. The species has been seen in 18 countries between the years 1900-2001. Below is a list of both confirmed and unconfirmed sightings of the bird organized by country:

Russia

The most documented sightings of Slender-Billed Curlews in Russia come from the first-hand accounts of V.E Ushakov in the early 20th century (1909-1924). According to Ushakov who first started writing about the species in the area in 1909, Slender-Billed Curlews were common around Tara (especially in the big marshes at Krasnoperovaya 13 km south, southwest of Tara). This species liked open marshes with some birch Betula and marshy areas bordering pine forests. In the Spring, birds of this species would usually arrive a week later than the Eurasian Curlew and not before May 10. Slender-Billed Curlews would nest in the middle of the marsh on grassy hillocks or on small dry islands in an area of 10-15 square meters. The nests were made in a shallow hollow with little dried grass. Ushakov reported clutches of 4 eggs that were found between May 30 and June 11. The young would fledge in early July and stay close the marsh where they were born. Family groups consisted of 5-6 birds by early August.

Since 1909, Ushakov noted that the numbers of Slender-Billed Curlews around Krasnoperovaya became less and less. He remarked that at the game market he found only 1 Slender-Billed Curlew for every 100 Eurasian Curlew.

On June 3, 1912, Ushakov and V.S Stolbov went to a peat bog near Krasnoperovaya and Osinovski Vyselek. This was a site with a dense pine forest to the southwest surrounded by birch, sedges, horsetails, and sparse reeds. There they saw two Slender-Billed Curlews mob a Carrion Crow (Corvus corone) with their bills that was accompanied by a "hollow vibrating whistle" that reminded Ushakov of a Marsh Harrier (Circus aeruginosus). He noted that the Slender-Billed Curlews did not do any sudden attacks like their relative the Eurasian Curlew. He also saw a Slender-Billed Curlew join a pair of Northern Lapwings (Vanellus vanellus) in mobbing a Black Kite (Milvus migrans). The marsh where Ushakov saw the Slender-Billed Curlews also had Eurasian Curlews, Ruffs (Philomachus pugnax), Common Cranes (Grus grus), Black-Throated Divers (Gavia arctica), and Pine Buntings (Emberiza leucocephalos).

On May 29, 1916, Ushakov found a nest with four eggs 1 km from Krasnoperovaya. Eight years later on May 20, 1924, Ushakov followed a flock of 20 Slender-Billed Curlews to their nesting site on one of the many islands in a huge peat bog south of Tara. He found 14 nests with most of them containing 2 eggs. It must be said that it is possible that some of the eggs he saw in 1924 might have come from Eurasian Curlews based on the descriptions he provided.

1908-1991- 9 records (3 birds)

1975-2000- 4 records with 3 unconfirmed (Galo-Orsi et al., 2002)

July 9, 1996- A Slender-Billed Curlew was seen in flight in Tara in western Siberia (Gretton et al., 2002).

Morocco

1939-1994- 53 records (500-800 birds) with 3 unconfirmed

1975-2000- 12 records with 3 unconfirmed

Important sites include Merja Zerga with 29 records since 1975, Casablanca with 3 sightings since 1975, and Oued Smir with 7 records between 1975 and 1988 (Galo-Orsi et al., 2002).

1964- 500-800 birds were seen in southwest Morocco

1986-1995- 1-5 Slender-Billed Curlews were seen regularly at Merja Zerga

Every two years there was a loss of 1 Slender-Billed Curlew in Merja Zerga starting in 1986: 5 in November 1986, 4 in 1988, 3 in February 1989, 1990, 1991, and 1992, 2 in 1993 and 1994 with the last in 1995 (Van der Halve et al., 1998)

February 23, 1995- The last Slender-Billed Curlew was seen at Merja Zerga. This is considered the last confirmed sighting of the species that has not been disputed.

Italy

1900-1993- 76 records (7 birds) with 6 unconfirmed

1975-2000- 13 records (19 birds) with 2 unconfirmed

Important sites include Circeo National Park with 1 record since 1988, Laguna do Orbetello/Maremma Regional Park with 1 record since 1975. Uncontrolled hunting is a concern as it does happen next to or within protected areas (Galo-Orsi et al., 2002).

January-March 1995- 20 birds were seen in southern Italy (many have rejected this sighting)

March 1996- A photo of a Slender-Billed Curlew was taken in Sicily (Kirwan et al., 2015)

Iran

1911- One Slender-Billed Curlew was seen in the South Caspian region and in Sistan

December 20, 1939- One was seen at Bandar Abbas

1963-1973- 6 records (7 birds) with 35 unconfirmed

1975-2000- 21 unconfirmed records (Galo-Orsi et al., 2002)

August 23-27, 1963- Another was seen at Bandar-e Gaz on the southern side of Gorgan Bay in Mazandaran

April 25, 1967- 3 were seen in the mudflats at Bandar Abbas with 7 being seen in the same area on April 30 of the same year (Scott, 2008)

1994- 50 Slender-Billed Curlews were seen in Iran (Kirwan et al., 2015)

Hungary

1903-1991- 85 records (36 birds) with 1 unconfirmed

1975-2000- 10 records

Key sites include Hortobagy with 4 records since 1975 and the Viragoskut fish ponds in Balmazujavros with 3 records since 1988 (Galo-Orsi et al., 2002)

April 15, 2001- A Slender-Billed Curlew was a seen in the Kiskunsag National Park. This is seen by many as the last accepted sighting of the species even though many contend the sighting’s credibility. It also marks the first and only sighting (confirmed and unconfirmed) of the species in the 21st century. Before this sighting, there were only unconfirmed sightings of the bird in 20th century in the Hungarian Plains between March and October in sodic pens and drained fishponds. Janos Olah was watching birds with a group of Japanese birdwatchers at Kiskunsag on an alkaline steppe in the morning when they saw a small curlew fly in front of them from the southwest. They could not judge the size of the bird but the short bill reminded them of a Slender-Billed Curlew. They were observing hundreds of Ruffs and Black-Tailed Godwits (Limosa limosa) along a road that connected Apaj and Urbo. The suspected Slender-Billed Curlew landed on a former paddy field in Apaj in the Perjes hay lands 200-300 meters away. After a few minutes, the curlew was seen in high vegetation on a wet meadow. Olah and the group observed the bird for 15 minutes when the bird flew away with other birds to the north before descending on a former rice plot. They found the bird again feeding on high vegetation. They lost sight of the bird for a few minutes to change position. They returned to the rice plot and found the curlew near three Ruffs. They did not see the bird again due to the size of the area and the sheer number of shorebirds present.

This sighting was accepted in 2005 by the Hungarian Rarities Committee. However, this sighting still remains controversial to this day. According to the description by Olah, this bird seems to be a match to the Slender-Billed Curlew, "it needs to be added that it appeared as a very small sized curlew, with an identical size to Black-tailed Godwit and it was just slightly larger than a male Ruff. Its whole appearance was more graceful and its position was more upright. According to its size and its bill length we assumed it to be a male individual."

The bird in question had a short bill similar to the Slender-Billed Curlews seen in Morocco. The bill was one and half times the length of the head, entirely dark, and had a thick base with a gradually tapering with a slight curve downwards. The bird had greyish plumage with a warm, brownish colored part on head that looked like a cap (a trait overlooked by field guides and seen on Slender-Billed Curlews in Morocco). The bird had no crown stripe on the cap, a greyish light head, dark lores, an almost white throat, snow white underwings with darker primaries, white shafts on the first and second primaries, dark upperwing-coverts, a pale wing panel pattern on the secondaries, a lighter uppertail and rump with fewer stripes on the tail, light-colored flanks with spots, and dark shorter legs compared to other species in the area. The suspected Slender-Billed Curlew was alone but occasionally seen with other shorebirds like Ruffs where it was hard to observe in high vegetation. Olah noted that he had experience is observing Slender-Billed Curlews in Morocco and could tell the difference between this species and Eurasian Curlews. To this day, he believes the bird he saw was a Slender-Billed Curlew (Olah and Pigniczki, 2010).

Britain

May 1998- there was an unconfirmed record of a curlew at Druridge Bay that was accompanied by video and photographic evidence. This record was later rejected due to the evidence presented being considered doubtful by experts.

Albania

1992-1993- 2 records (5 birds) that were seen in Fushe-Kushe Patok and Butrintit (Galo-Orsi et al., 2002)

Algeria

1977-1990- 7 records 1977-1990 (37 birds). Three of these records are unconfirmed. Sites where the Slender-Billed Curlew was seen are Sebkret Guellal, Mostaganem-Cherchell, Sebkhet Baker, Nr. Chott El Frain, Sebkret Ez Zemoul, Chott El Tarf, and GDE Sebkha d'Oran

In the late 1980s, 30-90 Slender-Billed Curlews were seen in the country (Galo-Orsi et al., 2002)

Croatia

1970-1987- 5 records (2 birds) with 1 unconfirmed

1975-2000- 5 unconfirmed records

Between 1970-1987, it has been reported that 5 Slender-Billed Curlews were shot by hunters (Galo-Orsi et al., 2002)

In August 1999, it is suspected that some Slender-Billed Curlews may have been part of a larger, mixed flock of 36 which was shot down in the country by Italian hunters. The only photo of one of these birds has been confirmed to be a Eurasian Curlew. This casts doubt on whether Slender-Billed Curlews were really part of that flock (Galo-Orsi and Boere, 2001).

Iraq

1917-1979- 3 records (6 birds)

It must be said that the marshes in Iraq have never been fully surveyed. They are also the most susceptible to habitat modification and development (Galo-Orsi et al., 2002)

December 16, 1917- One Slender-Billed Curlew was seen in Amara

January 27, 1979- One was seen in Haur Al Hammar in Nasiriya (Kirwan et al., 2015)

Former Yugoslavia (Montenegro, North Macedonia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Serbia)

1900-1984- 38 records (50 birds). 32 of these records were from the region of Vojvodina alone.

Between 1962-1968, two Slender-Billed Curlews were shot in Vojvodina. These records prompted some researchers to launch a survey in Vojvodina between 1988 and 1990. No Slender-Billed Curlews were found (Galo-Orsi et al., 2002)

Cyprus

April 23, 1958- A Slender-Billed Curlew was seen in Famagusta

December 22, 1964- One was seen in Nicosia

April 28, 1972- Another was seen in Cape Andreas (Kirwan et al., 2015)

France

February 15, 1968- Michel Brosselin saw and photographed a Slender-Billed Curlew amongst a flock of 150-200 birds at the Baie de l'Aiguillon near la Rochelle in France (Marchant, 1984)

Israel

October 4, 1917- One Slender-Billed Curlew was seen in Nahal Besor (Kirwan et al., 2015)

Netherlands

According to Pieter Mulder, the Slender-Billed Curlew may have been regular Winter visitor to the Zuiderzee area in the Netherlands before the construction of the Afsluitdijk in 1932. Mulder was the son of a hunter that shot and consumed curlews for a living. One curlew was known as the pikgulp. He described this bird as small and around the same size as a Black-Tailed Godwit. These birds never ventured inland. To prepare them for eating, Mulder had to remove small oily glands that were located in the lower abdomen. The pikgulp disappeared after 1932 when the Afsluitdijk turned the Zuiderzee estuary into a stagnant freshwater lake (Ijsselmeer). Based on his description, the pikgulp might be the Slender-Billed Curlew based on an examination of specimens of this species that were collected in Zuiderzee in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The pikgulp appearing in Winter rules out the Whimbrel that arrives between April and September. The pikgulp was found in saltmarshes and intertidal zones and never in freshwater inland habitats (preferences that match the Slender-Billed Curlew).

The oil glands of the pikgulp refer to two small abdominal patches of powder feathers. Powder feathers are modified feathers that grow continuously before shedding a fine powder consisting of granules of keratin. This type of feather is also present in some species of pigeon and heron. The main function of these feathers is to help with waterproofing. It is curious that none of these feathers were seen on any Slender-Billed Curlew specimens. Experts theorize that the taxidermists that prepared these specimens for display may have removed them. If the pikgulp really is the Slender-Billed Curlew, then that means that this bird had powder feathers. The reason why is unclear. Powder feathers are rare in Charadriiformes but all members of this order may have the gene (Jukema and Piersma, 2004).

Spain

1962-1980- 6 records 1962-1980 (13 birds) with 35 unconfirmed. Most of these records came from Coto Doñana (Galo-Orsi et al., 2002)

Oman

April 25-May 19, 1976- Slender-Billed Curlews were seen in As Seeb

January 5, 1990- One was seen in Abb Island

January 6, 1990- Another was seen in Filim

January 8, 1990- Another was seen in Bar Al Hikman

February 10, 1999- Two Slender-Billed Curlews were seen in Kwahr Dhurf. This sighting remains the last sighting of the Slender-Billed Curlew in the Middle East (Kirwan et al., 2015)

Yemen

January 1-2, 1984- One Slender-Billed Curlew was seen and photographed in Hodeidah by Richard Porter (Kirwan et al., 2015)

Greece

1918-1993- 70 records (150 birds) with 7 unconfirmed.

1975-2000- 53 records (8 of them unconfirmed) (Galo-Orsi et al., 2002)

January-March 1997- A Slender-Billed Curlew was spotted in the Evros Delta, Thraki

April 1997- One was seen in the Axios Delta, Macedonia. At the same time, two were also seen in Sagiada, Ipiros

April 1998- Three Slender-Billed Curlews were seen south of Lake Ismarida and two in Porto Lagos (both in Thraki)

May 1998- One was seen in Agiasma Lagoon, Macedonia

April 1999- Four Slender-Billed Curlews were spotted in the Evros Delta

May 1999- One was seen in Mesolonghi, Sterea Hellas (Kirwan et al., 2015)

Saudi Arabia

January 19, 1990- A Slender-Billed Curlew was seen at Jizan (Kirwan et al., 2015)

Bulgaria

Between the years 1869-1993, there have been 52 sightings of Slender-Billed Curlews involving 378 birds. This has led many to suspect that the country may have been an overlooked stopover for the species during migration. It also demonstrates just how rare the bird had become by the mid-20th century (Kirwan et al., 2015).

1903-1993- 19 records (4-7 birds) with 10 unconfirmed

1975-2000- 10 records with 9 unconfirmed. Key sites include Lake Atanasovo and Burgas that had 6 sightings each since 1975 (Galo-Orsi et al., 2002)

Kazakhstan

1921-1991- 4 records 1921-1991 (3 birds) with 31 unconfirmed (Galo-Orsi et al., 2002)

Romania

1966-1989- 16 records (30 birds)

1975-2000- 10 records (Galo-Orsi et al., 2002)

Tunisia

1915-1992- 26 records (32 birds) with 2 unconfirmed

1975-2000- 15 records with 2 unconfirmed (Galo-Orsi et al., 2002)

Turkey

1946-1990- 29 records (4 birds) with 3 unconfirmed

1975-2000- 8 records with 1 unconfirmed (3 of them from Goksu Delta) (Galo-Orsi et al., 2002)

Ukraine

1908-1993- 15 records (48 birds) with 18 unconfirmed

1975-2000- 20 records with 15 unconfirmed (Galo-Orsi et al., 2002)

Other Sightings

There have been unconfirmed sightings in the Seychelles.

Specimens collected from Myanmar and Montenegro were not Slender-Billed Curlews but were, in fact, a Eurasian Curlew and a Whimbrel respectively.

There was a possible sighting in Gujarat, India in March 2002 (Kirwan et al., 2015).

Global Statistics

1980-1990- 103 records globally involving 316-326 birds

1990-1999- 74 records involving 148-152 birds with most of these records concerning 1-3 birds

1980-1995- 25% of sightings were in Greece alone with 80% of these sightings in Evros Delta and Porto Lagos (Birds of the World)

Between 1900-1999, the distribution of sightings of Slender-Billed Curlews between the countries within her range are as follows:

Italy- 94

Greece- 85

Morocco- 75

Hungary- 66

Yugoslavia- 32

Ukraine- 30

Tunisia- 28

Turkey- 24

Bulgaria- 21

Romania- 17

Russia- 16

Other Countries- >10 (Galo-Orsi and Boere, 2001)

Challenges & Concerns

The most difficult challenge with regards to finding the Slender-Billed Curlew is identifying her. Thanks to a study conducted by Andrea Corso et al. (2014) where almost every known specimen of the species was examined, we now have an in-depth ID guide to help identify the Slender-Billed Curlew from her closest relatives: the Eurasian Curlew and the Whimbrel. The guide is divided into Essential, Secondary, and Unreliable criteria. The essential criteria are the main traits that reliably make the Slender-Billed Curlew recognizable from the Eurasian Curlew and the Whimbrel. Secondary criteria are less reliable due to the variability between the three species. The unreliable criteria refer to other criteria that have been mentioned by experts but must be taken with a grain of salt since studies have shown similar characteristics in Eurasian Curlews and Whimbrels. Below is a summary of their findings for your convenience:

Essential Criteria

Pattern and Color of the Underside of the Outer Primaries

For the Slender-Billed Curlew, this part is uniformly dark grey or blackish-grey with a dark wedge on the underside of the outer wing that contrasts with the paler inner primaries and outer secondaries. This is single most important feature that differentiates this species from the Eurasian Curlew and the Whimbrel because the latter two lack this dark wedge.

Tibia Length and Feathering

In Slender-Billed Curlews, white thighs are formed by long tibial feathering. Eurasian curlews have longer exposed tibia although some can have short exposed tibia.

Leg Color

Slender-Billed Curlews have blackish-brown or dark lead-grey legs for males and paler dark-brown or grey for females and juveniles. The leg color is darker than those of Eurasian Curlews and Whimbrels. These birds have pale lead-grey or bluish-grey legs that are sometimes pinkish or horn brown.

Tail Feather Pattern

Slender Billed Curlews have whitish tails with broken, dark-sepia barring. The dark bars on the tail are narrower and more regularly spaced. Eurasian Curlews and Whimbrels have darker central tail feathers with the ground color being much paler. Eurasian Curlews have fewer tail bars.

Underpart Pattern and the Shape of the Dark Flank Markings

Slender-Billed Curlews have dark spots on the belly and flanks. This is an important feature as these spots are heart- or drop-shaped on a whitish background. There is some variability in the species with a dark, subterminal, round to oval mark on the white flank feathers combined with other dark bar markings that looked sparsely barred from a distance. These dark bar markings are more conspicuous on Eurasian curlews and Whimbrels. Juvenile Slender-Billed Curlews do not have these dark flank spots with the underparts and flanks streaked on a paler background. Females are duller with buffish-tinged underparts with fewer rounded spots.

Secondary Criteria

Loral Pattern

Slender-Billed Curlews have solid dark lores.

Color of Axillaries

Slender-Billed Curlews have unmarked white axillaries.

Color and Pattern of Underwing-Coverts

These are unmarked and white in Slender-Billed Curlews.

Bill

The bill is less curved and more tapered for Slender-Billed Curlews than for Eurasian Curlews. It is also shorter, more delicate, and has a narrow base.

Size and Structure

Slender-Billed Curlews are similar in size to Whimbrels but are, on average, 20% smaller than Eurasian Curlews.

Wing-Tip to Tail-Tip Ratio

On Slender-Billed Curlews, the wings project beyond the tail tip.

Primary Projection

Slender-Billed Curlews have a longer primary projection than Eurasian Curlews.

Uppertail-Covert and Rump Pattern

In Slender-Billed Curlews, the rump pattern is less strongly patterned than in Eurasian Curlews. The rump and uppertail-coverts are also cleaner and a brighter white with rounded dark markings.

Supercilium

Slender-Billed Curlews have a clean, demarcated supercilium (especially in males) in front of the eye.

Capped Appearance

Slender-Billed Curlews tend to have a more capped appearance than their Eurasian Curlew and Whimbrel relatives.

Unreliable Criteria

Pectoral Band

In Slender-Billed Curlews, a contrast has been noted between the clouded streaks on the breast and the spots on the flanks and belly.

Upperwing Pattern

There is a contrast between the dark outer and paler inner primaries on the Slender-Billed Curlew.

Undertail-Coverts

These are white and unmarked in Slender-Billed Curlews.

Upperparts

Slender-Billed Curlews have a fringing and spotting on feather edges that is narrower than those of the Eurasian Curlew.

Contrast between the Mantle, Scapulars, and Wing-Coverts

There is contrast between these three parts on the Slender-Billed Curlew.

Crown Stripe

The crown stripe is narrow and poorly marked on the Slender-Billed Curlew.

Eye Ring

Slender-Billed Curlews tend to have a more conspicuous eye ring.

White Chin

Slender-Billed Curlews usually have a white chin.

Foot Projection Beyond the Tail

The feet usually project beyond the tail on a Slender-Billed Curlew.

Voice

The only undisputed recording attributed to a Slender-Billed Curlew was made by Adam Gretton in January 1990 at Merja Zerga, Morocco. If one takes the recording as an example, the jizz- jizz is different than that of the Eurasian Curlew.

Caveats

There is a lot of plumage variation between Slender-Billed and Eurasian Curlews which can lead to confusion even among the most experienced of birdwatchers. Generally speaking, Slender-Billed Curlews are more elegant and compact, have a well-proportioned body, are pot-breasted appearance rather than hump-backed, and have wings that are narrower in flight with a pointed "hand." The wing action is faster with Slender-Billed Curlews than Eurasian Curlews with quicker wingbeats and a faster gait that reminds one of the movements of the Black-Tailed Godwit. Small curlews that resemble Slender-Billed Curlews have been observed in Sicily and Puglia that have similar characteristics to the species. These includes traits such an unmarked white underwing, a narrow bill, a white rump, undertail-coverts with few markings, and a pale tail. These birds have been confirmed to be Eurasian Curlews that were not discussed by other ornithologists. Identifying Slender-Billed Curlews from Eurasian Curlews is the biggest challenge in terms of identification. Many birds in the past that were identified as Slender-Billed Curlews turned out to be Eurasian Curlews. With this in mind, Corso et al., conclude that a mass reevaluation needs to be done of all records regarding the Slender-Billed Curlew to ensure that none of them were cases of misidentification with more common species of shorebird (Corso et al., 2014).

No one is sure what exactly caused the decline of the Slender-Billed Curlew over the course of the 20th century. There have been several theories proposed over the years:

Habitat Loss

It is thought by many experts that the loss of the Slender-Billed Curlew’s breeding grounds in the steppes of western Siberia and northern Kazakhstan was one of the main (if not the principal) cause of the species’ decline. This was combined with the drainage of wetlands in the Mediterranean, North Africa, and Iraq used for the bird’s staging areas during her winter migration. This degree of habitat loss continues to this day, ever minimizing the species’ chances for survival. It is curious that recent surveys to Western Siberia have noted that the taiga environment mentioned by Ushakov as a primary breeding habitat for the Slender-Billed Curlew remains intact. The forest steppe, however, has been partially modified for agriculture. While the taiga and forest steppe in Russia remains mostly intact, the same cannot be said for other potential breeding sites outside the country (IUCN Red List).

Essential steppe environments in Central Europe and Kazakhstan have been destroyed and turned into agricultural fields. Experts have noted a relation between the declining numbers of Slender-Billed Curlews in their wintering sites in Northwest Africa and changes in the steppes of Kazakhstan. While there have been reports of Slender-Billed Curlews nesting in the steppes of Ukraine, Romania, and Turkmenistan in the 19th century (particularly those close to Odessa, the steppes of Dobroudja, and the oasis Achal-Teke in marshy steppe lands between the Kissyl-Arvat and Ashkabad villages), most of these areas have long since vanished. The final records where large flocks (600-900 birds) of Slender-Billed Curlews were recorded in their wintering sites between Merja Zerga and Puerto Cansado in Morocco were in July 1953, October 1958, and January 1964. The decline of these flocks coincided with the New Country Policy that was enacted in Kazakhstan starting in 1953 under the Soviet Union. This program converted 18 million hectares of steppe into farmland in the span of 3 years (1953-1956). The number of goats and sheep in the area increased by 65%. According to Jacques van Impe who investigated this correlation, “there are serious reasons to admit that the near extinction of the Slender-Billed Curlew is, first and foremost, due to the disappearance of its privileged breeding habitat” (Translated from the French by Nick Ortiz). The loss of these habitats severely hinders the ability of the species to breed and survive. This correlation shows that the breeding sites of the species was much larger than previously thought. Van Impe suggests that the Aralo-Caspian steppes where there is less contact with the West should be investigated. They might serve as a potentially undisturbed breeding ground for the Slender-Billed Curlew (Van Impe, 1995).

Hunting

The Slender-Billed Curlew was hunted throughout the 20th century. This unregulated hunting occurred especially in the species’ stopover sites in Western and Southern Europe (such as Italy) (IUCN Red List). This species was seen as tamer than Eurasian Curlews and thus seen as easier prey. There were records of Slender-Billed Curlews being sold in Hungary and Italy. Between the years 1962-1987, a total of 17 Slender-Billed Curlews were shot (13 in Italy and the former Yugoslavia). In 1995, one of the last three Slender-Billed Curlews at Merja Zerga was injured as hunters regularly operated throughout the Maghreb. As the population grew smaller and smaller, the pressure from unregulated hunting in the Maghreb and Europe further threatened the species with extinction (Galo-Orsi et al., 2002).

Breakdown in Social Behavior

As the species’ numbers declined due to habitat loss and hunting, this may have led to a breakdown in social behavior. This is especially the case with migration as this behavior is passed down from generation to generation through direct learning. As numbers dwindled and the flocks became smaller and smaller, surviving Slender-Billed Curlews began to join flocks of other shorebirds (especially those of Eurasian Curlews) for safety and guidance. This led them to sites that were inappropriate in terms of breeding and wintering and reduced the chances of these birds finding a mate. As a result, a lot of Slender-Billed Curlews either could not find mates or mated with other shorebirds to produce hybrids. This breakdown led the species to the brink of extinction (IUCN Red List).

Other Causes

Other potential causes of the Slender-Billed Curlew’s decline are the heavy use of chemicals in the Aral Sea. Another is nuclear testing near Ust-Kamenogorsk and Semipalatinsk during the Soviet Union in the 1920s and 30s. These were two areas that did report receiving Slender-Billed Curlews in the early 20th century (Galo-Orsi et al., 2002).

It is curious that numerous, detailed surveys have been done in almost every part of the Slender-Billed Curlews suspected breeding and non-breeding ranges and no trace has been found of the species.

It is possible that if a Slender-Billed Curlew or a nest is found that the birds’ discovery would not be made public (at least not immediately). According to the Slender-Billed Curlew Working Group, any discovery must be kept confidential while the appropriate conservation measures are undertaken. They did not specify what these measures might be. They also mentioned that there are protocols between the Slender-Billed Curlew Working Group and the Russian Bird Conservation Union if such a situation arises (Gretton et al., 2002).

Research Priorities

Previous surveys must be reviewed to see if there are any sites that still need to be investigated. There are many that have been overlooked by birdwatchers in the Mediterranean, Red Sea, Black Sea, Sea of Azov, Caspian Sea, Pannonian plain of Central and Southeast Europe, Persian Gulf, and Arabian Peninsula (Crockford, 2009).

Many sightings of the Slender-Billed Curlew have been reported among large flocks of shorebirds such as the Eurasian Curlew, Black-Tailed Godwit, Whimbrel, and Ruff. If it is true that habitat loss and unregulated hunting have led to a drastic population decline in this species, it is possible that any surviving Slender-Billed Curlews have not been taught how to get to their traditional breeding grounds in the steppes of Kazakhstan and Russia or their wintering sites across the Mediterranean. Instead, they would probably follow other shorebirds. The migratory routes and wintering sites of the aforementioned species should be examined closely by birdwatchers to see if any Slender-Billed Curlews are following them.

For a list of key sites where the Slender-Billed Curlew has been found, click here.

To see a map of Slender-Billed Curlew sightings since 1990, click here.

Ongoing Work

Surveys

Russia and Kazakhstan

Three expeditions searched the site south of Tara where 14 nests were found by V.E Ushakov in 1924. These were launched in 1989, 1990, and 1994 respectively.

During the 1989 expedition, Alexander K. Yurlov and Gerard C. Boere surveyed between 2,600-3,200 km. They examined taiga areas and a vast complex of lakes and marshes. They were unable to find any nests or Slender-Billed Curlews. Surveys conducted in 1990 and 1994 were equally unsuccessful.

Surveys in 1996 and 1997 discovered 22 potential breeding sites across Russia that included the wetlands of southwest Siberia which are located in the narrow forest steppe zone between the dry steppes of Kazakhstan to the south and the taiga to the north of Krasnoperovaya. It is worth noting that Tara is at the northern limit of the forest steppe zone. Unfortunately, four of these sites have since been destroyed by drainage. Additional surveys were done in the general region in 1998 and 1999 followed by other surveys by Birdlife International. Even though more was learned about existing suitable breeding habitats, no trace was found of the Slender-Billed Curlew (Galo-Orsi et al., 2002).

During the 1990 and 1994 expeditions, areas such as Barnaul and Chelyabinsk were surveyed. At the time, there was still a lot of marsh at Krasnoperovaya. This was the same marsh that Ushakov reported seeing Slender-Billed Curlews nesting. By 1997, a lot of grassland had already been converted into farmland near the marsh. The marsh itself was covered with young forest. This made it very unlikely that any Slender-Billed Curlews would still use this area as a nest site. The expedition failed to find the Slender-Billed Curlew.

In 1997, G.C Boere and A.K Yurlov searched the Baraba and Karasuk steppes in Russia and the eastern side of Lake Ubinskoe. They did not find any Slender-Billed Curlews (Gretton et al., 2002).

From July-September 1998, a survey was conducted by the Glasgow University in northern and eastern Kazakhstan. No Slender-Billed Curlews were found.

In 1999, a survey led by G. Boyko was done in the Tuman plains and Omsk region in Russia. This was coincided by another survey by A.K Yurlov in the eastern side of Lake Ubinskoe. No traces of the Slender-Billed Curlew were found (Galo-Orsi and Boere, 2001).

Most of these expeditions visited the following sites in Russia and Kazakhstan. These sites may prove useful for future expeditions seeking to find the elusive Slender-Billed Curlew in her breeding grounds:

Russia

Upper reaches of the Ural River 220 km to southwest from Chelyabinsk

Area between the Techa and Miass rivers 110 km to the northeast from Chelyabinsk

Kugar region area on the left bank of the Tobol river 130 km to the north from Kustanay

Tumen region in the area between the Tobol and the Irtysh rivers 90 km to south from their confluence

Tumen region in the area between the Tobol and Irtysh rivers 70 km to southeast from their confluence

Tumen region 160 km to northwest from Tara town

Omsk region 160 km to west from the Tara mouth

Boundary between the Omsk and Tumen regions in the upper reaches of the Osha river on the northern coast of Tenis Lake

Omsk region area between Omsk and the Irtysh River 190 km to northeast of Omsk

Novosibirsk region in the southeast core of the Maliye Chany lake 320 km to west-southwest from Novosibirsk

Novosibirsk region in the northeast corner of Ubiskoye Lake 180 km to northwest from Novosibirsk

Boundary between Novosibirsk region and the Altay region in the Burla Valley 260 km to northwest from Barnaul

Boundary between the Novosibirsk region and the Altay region 150 km to northwest from Barnaul 40 km to south from the Novosibirsk water reservoir

Altay region area on the right bank of the Ob 50 km from the confluence of the Biya and Katun rivers

Altay region area on the left side of the Alei river 60 km to north from the Lokot settlement

Tomsk region area between the Chulym and Ob rivers 40 km to southeast from their confluence

Upper reaches of the Ilovlya river 120 km to northwest from Saratov

Northern coast of the Volga 60 km to northeast from Saratov

Left side of the Volga in the Ulyanovsk region 60 km to east from Saratov

Boundary between the Samara and Orenburg regions and Bashkiria on the right side of the Bolshoy Kinel river in its middle reaches 140 km to northeast from Samara

Boundary between the Samara and Orenburg regions and Bashkiria in the Yia River basin 170 km to west southwest from Ufa

Boundary between the Samara and Orenburg regions and Bashkiria in the Yia River basin 180 km to west southwest from Ufa

Kazakstan

Lake Tengiz Ramsar site

Naurzum

Kustani lakes

Shoskally Hunting Reserve

Lakes in the Petropavlosk region in northern Kazakhstan

Lakes in the central region of Kazakhstan

Taldy Kurgan in northeastern Kazakhstan

Sasykkol in northeastern Kazakhstan

Lake Zayshan in northeastern Kazakhstan

Lakes of Kalbinsky in the Altai mountain range

Lake Alako in northeastern Kazakhstan

Iran

Over the years, several surveys have been done in Iran. Surveys were done in 1990 by Birdlife International that turned up 4 unconfirmed records. D.A Scott and M. Smart visited Iran in the winter of 1992 and 1993. There were two expeditions in 2000 and one in 2002. With the exception of the 1990 expedition that had 4 unconfirmed sightings, most surveys in the country have failed to find the Slender-Billed Curlew (Galo-Orsi et al., 2002).

In the early 2000s, two expeditions were done by a Dutch-Russian team led by T. van der Have and F.V Morozov and a French team led by Phillippe Dubois in Iran. The expeditions did not locate any Slender-Billed Curlews but found a large amount of suitable habitat for the species in the areas of their search (Galo-Orsi and Boere, 2001).

From January 9-29, 2004, 10 Dutch birders went to Iran to help with the mid-winter waterbird count. They visited different provinces and counted 1.5 million waterbirds. These provinces were Gilan, Mazandaran, Khuzestan, Hormozgan, Sistan and Baluchistan, and Touran. Important habitats were examined at the Miankaleh Wildlife Refuge that included mudflats and lagoons to creeks in Hormozgan on the coastal areas from the Straits of Hormuz to the border with Baluchistan. They commented that several of these sites were vast and inaccessible. They saw many Eurasian Curlews but no Slender-Billed Curlews (Van Diek et al., 2014).

Tunisia

A team led by T.M van der Halve was conducted from February 9 to March 5, 1994 in Tunisia. Van der Halve and his team surveyed 31 wetlands located across Tunisia. They identified suitable sites that were similar to Merja Zerga in Morocco such as Soliman Lagoon. They also investigated other sites such as Tazerka, Garaet Kebira, Halk el Menzel Coast, Kairouan, the Thyna salines, Djerba, Zarzis, Bahiret el Bibane, and El Marsa. Many of the marshes around these sites were damaged from the construction of dams that caused long periods of droughts. After identifying 4,000 curlews and more than 1,600 Black-Tailed Godwits, no Slender-Billed Curlews were found.

Four surveys were done in Tunisia from February-March 1992, November 1992-January 1993, February-March 1994, and January 1997. Other areas of suitable habitat were identified such as Sebkha Asa Jiriba and Sebka Sidi Khalifa north of Hergla and east of Enfidaville respectively. According to those that surveyed these sites, it is possible that the Slender-Billed Curlew could visit many of these sites along with the Eurasian Curlew. Both of these sites have been overlooked by birdwatchers. Van der Halve and his team concluded that Tunisia could still be a wintering area for the Slender-Billed Curlew even though none were found by him or his team. A wintering population might be easily overlooked due to its tiny size (1-5 birds) and may come at different times of the year other than between September and February when the surveys were conducted. They also note that Slender-Billed Curlews can hide while foraging in dry salt scrub and agricultural fields. They suggest that future surveys check wader roosts in the morning and the evening as Slender-Billed Curlews at Merja Zerga were known to use these roosts in conjunction with other waders (Van der Halve et al., 1998). A similar survey was done in the wetlands of southern Morocco in December 2001. All of these surveys were equally unsuccessful in finding any Slender-Billed Curlews (Galo-Orsi et al., 2002).

Saudi Arabia

From January 10-22, 2011, the Slender-Billed Curlew Working Group and the Saudi Wildlife Commission organized an expedition to search for the Slender-Billed Curlew in Saudi Arabia. They examined suitable habitat on the Red Sea coast that had open sand and mud flats, coastal dunes, freshwater lakes, and sewage disposal ponds. They noted that many of these habitats were negatively affected by development. They searched many sites that included the Farasan Islands, Sabya sewage ponds, Malaki Dam, Lalmuwassam, Jizan Bay, Abha Dam, Al Shugaig/Al Qahma, Wadi Alassahbah/Al Lith, Dahaban in North Jeddah, a lake southeast of Jeddah, Jeddah South Corniche, Al Shugaig/Al Qahma, and Wadi Alassahbah/Al Lith. They counted 224 Eurasian Curlews and 121 Whimbrels. The majority of these birds were located in sand and mudflats on the Farasan Islands. Unfortunately, they did not find any Slender-Billed Curlews (Ahmed et al., 2011).

Europe

Several surveys have been done in Greece in the last few decades. From 1987-1988, the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) in conjunction with the Hellenic Ornithological Society surveyed the Evros Delta in Greece. Around the same time, V. Goutner and Birdlife International conducted surveys in northern Greece. Both of them failed in their quest to find the Slender-Billed Curlew.

From 1990-1994, several surveys were conducted in Spain in search of the Slender-Billed Curlew. The main sites investigated were Doñana and other sites on the Andalusian coast. Their efforts to find the elusive species was unsuccessful.

During the 1980s and 1990s, the Working Group for International Waterbird and Wetland Research (WIWO) conducted surveys at important wetlands in Turkey. No Slender-Billed Curlews were found.

WIWO conducted other surveys in Ukraine. One was done at Savash in the early 90s. In 2001, a group of 12 ornithologists were trained by an expert and sent to survey 3 sites in Ukraine. They identified 12 birds that could potentially be a Slender-Billed Curlew. These sightings are cast into doubt since these records do not come with good descriptions or photos. Sites investigated were Molochnyy Liman, Kivilovka, the Black Sea Nature Reserve, Tendra Island, Danube Delta, and Lebyashi Island in the Crimea (Galo-Orsi et al., 2002).

New Evidence Regarding the Species Breeding Range in Northern Kazakhstan

In 2017, Graeme Buchanan and a team of researchers analyzed hydrogen isotopes in the feathers of juvenile Slender-Bill Curlew specimens feathers and compared these isotopes to feather samples in other surrogate wader species. They examined 35 museum specimens for their project. According to them, the majority of the specimens came from a band that included the Kazakh forest steppe and the Kazakh steppe environments. This means that the potential breeding area for the species is in the Kazakh steppe further south that also extends eastward into the Altai steppe. They identified another site north of the Urals. It is a narrow band that stretches across southern and northern Kazakhstan. This suggests that the species may have been a specialist in steppe environments. The analysis by Buchanan et al., implies that the Slender-Billed Curlew’s breeding range is not centered in the Omsk region in Russia since Tara (the place where nests were found) is situated at the northern edge of the range. It is more probable that this range is situated south of Omsk and reaches as far as Zmeinogorsk. They also point out potential sites west of the Urals and east of Kazakhstan in the Altai in Russia for future surveys.

Surveys were done in the areas where Buchanen et al., indicated were part of the Slender-Billed Curlew’s breeding range. According to these surveys, most of the environments remained the same. However, the areas surrounding these environments were converted to support agriculture. These areas have undergone a radical transformation in the 19th and 20th centuries where much of the Eurasian steppes from Ukraine to the Altai Mountains were converted to agriculture. As part of the Virgin Land Campaign during the Soviet Union (1953-1960), it is estimated that 25.4 million hectares were converted in the steppe belt in Kazakhstan. The goal of the program was to support large-scale wheat farming. If the steppe belt was really the center of the species’ range, then the mass habitat modification during this time may explain its decline. The areas cited as having the highest probability of being within the breeding range are in the northern steppe of Kazakhstan. The environments in these areas have been heavily wiped out by farming. The remaining steppe has poor soil. Furthermore, the loss of grasslands led to extinction of the Rocky Mountain locust (Melanopus spretus) which was seen as an important food source for the Slender-Billed Curlew. Despite this, it seems that the species may have been already been in decline as early as the 1920s long before the mass agriculture programs of the Soviet Union in Kazakhstan.

The findings by Buchanan et al. suggest that habitat loss may not have been the main cause of the Slender-Billed Curlew’s decline but was, in fact, habitat modification which may have hindered breeding populations and opened up the area to predators. This breeding range is so large that a small breeding population of Slender-Billed Curlews could easily have been overlooked. It is possible that a population still breeds there (Buchanan et al., 2017).

Reexamination of Existing Records

There has been a trend among ornithologists to critically review all records and specimens attributed to the Slender-Billed Curlew to ensure that none were misidentified. Many records of the Slender-Billed Curlew come from the Middle East. It is unclear whether the species wintered in the region or was simply a vagrant. Large flocks of Slender-Billed Curlews were reported to have wintered in Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia in the 19th century. Flocks of more than 100 Slender-Billed Curlews were seen in Morocco in the 1960s and 70s (Galo-Orsi et al., 2002).

A review was recommended for the records in the Middle East. Such a review was done by a team led by Guy Kirwan (2015). They examined all records in the Middle East that included Bahrain, Cyprus, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Turkey, UAE, and Yemen. Among their most important findings came from Iran. After a thorough review of the records taken from the 1960s to the 1990s, they deemed only one record as being acceptable. What interested them were 31 reports in the 1980s and 45 in the 1990s. All of these records were taken by B. Behrouzi-Rad at the Miankaleh Wildlife Refuge in the Mazandaran Province in the southeast Caspian and in the Mehran Delta in the Hormozgan Province in the southern Persian Gulf. At Miankaleh, 3 Slender-Billed Curlews were seen in the Spring and 6 in the Fall during the 1980s. At the Mehra Delta during the 1990s, 8 Slender-Billed Curlews showed up in the spring with 12 in the Fall and 12 in the Winter. Most of the records from the 1990s came from the midwinter waterbird counts that were conducted by Behrouzi-Rad and the Iran Department of the Environment's waterbird census database in January from 22 sites. Most of these sites came from the southeast Caspian and along the Persian Gulf coast with some in the central Fars Province, Persian Baluchistan, and the Khuzestan province. The highest count was 28 Slender-Billed Curlews at Dasht-e-Arjan in central Fars on January 10, 1991. There were three counts of 20 at the Miankaleh Wildlife Refuge on January 13, 1992 and January 20, 1996 and at Fereidoon Kenar Ab-bandans in Mazandaran province on January 19, 1998.

Surveys were done by birdwatchers and ornithologists outside Iran at many of these sites in January-February 2000 and January 2002. The fact that they did not find any Slender-Billed Curlews cast doubt on the records. Suitable habitat was found along the Persian Gulf coast however. Furthermore, experts from WIWO participated in the midwinter waterbird counts in all major wetland regions in Iran in 2004, 2005, 2007, and 2009. None of these counts showed any Slender-Billed Curlews.

According to Kirwan et al., most of the records in Iran were sightings of Eurasian Curlews and Whimbrels that were misidentified by observers. They point to the fact that the Miankaleh Wildlife Refuge (as well as other regions with suitable habitat throughout Iran) were heavily surveyed by government officials and international expeditions in the 1960s and 1970s. Only a handful of sightings were recorded of Slender-Billed Curlews but these were seen in other parts of Iran and not in Miankaleh. With birdwatchers and government officials keeping such a close eye on this place, it seems unlikely that members of this species would suddenly appear in the 1980s and 1990s. There is considerable variation among Eurasian Curlews in Iran where many of them can look like Slender-Billed Curlews. This is especially the case with most recent records from Iran from B. Behrouzi-Rad and Khor Musa in February 2001, from Ghabreh Nakhoda in Khor Masa in Khuzestan province in January 2004, and records of seven sightings at Miankaleh Wildlife Refuge on February 6, 2003. A video was taken of the first record with the bird in the video turning out to be a Eurasian Curlew. Kirwan and his team dismissed the others after a careful examination. In conclusion, Kirwan et al., argue that most records of the Slender-Billed Curlew in Iran are doubtful and that the bird should be considered a rare vagrant in the country.

Another country that Kirwan and his team critically examined was Turkey. There were many unconfirmed sightings of the Slender-Billed Curlew in the country during the 20th century before 1975 with most of them occurring between 1966-1975 (15 out of 28). Sight records include:

3 records from Buyukcekmece west of Istanbul in 1946, 1947, 1951

2 at the Meric Delta in Thrace on February 27, 1959

1 at Hoyran Golu on January 14, 1967

2 at Mogan Golu on January 14, 1967 with two at the same place on March 19 and one on March 23, 1967

2 at Bahkdami on March 26, 1967

1 at Sodali Golu on August 12, 1967

1 at Amik Golu on October 10, 1968

3 near Tekirdag on April 5, 1969

2 moving west past Side, Antalya province on April 15, 1969

1 at Seyfe Golu on December 12, 1969 near Yarma on April 28, 1970

1 at Eber Golu on May 12, 1970

1 at Çivril Golu on January 17, 1971

1 near Rize on August 25, 1971

1 at the Goksu Delta on August 28, 1973

2 at Uluabat Golu on September 30, 1973

1 at Kuçuk Menderes Delta on September 23, 1979

1 at Akyatan Golu, Çukurova on January 5, 1982 and March 4, 1985

4 at the Goksu Delta on March 9, 1985

1 at the Eregli Marshes on April 6, 1986

1 at Çukurova on April 30, 1986

1 at the Goksu Delta on July 10, 1986

1 at the Buyuk Menderes Delta on December 26, 1986

1 at the Dalyan Delta on August 22, 1990

1 at Kulu Golu on May 10, 1993

Many records were either destroyed in a fire where the Turkey Bird Report records were kept. Others had incomplete descriptions. It is for these reasons that Kirwan et al., had no choice but to reject all of these records from Turkey.

Other records that Kirwan and his team rejected includes the following sightings from the following countries:

Kuwait

January 12, 1967- 5 birds in Kuwait Bay

United Arab Emirates

November 14, 1997- 4 birds at Al Ghar Lake

Yemen

October 6, 1988- 1 bird at Al Mokha

October 7, 1988- 1 bird at Al Kwakhah

Kirwan et al., conclude that most of the records of the Slender-Billed Curlew from the Middle East are doubtful due to incomplete descriptions, destroyed records, or cases of misidentification. They point to misidentification as the main cause of confusion. The Slender-Billed Curlew can easily be confused with other species in the Middle East such as the Whimbrel that is a passage migrant in the region and the suschkini subspecies of Eurasian Curlew. Other factors that promoted misidentification was the fact that suboptimal equipment was used in the 1960s and 1970s. Furthermore, many observers in Greece and Turkey expected to see Slender-Billed Curlews and these expectations may have affected their judgement in the field (Kirwan et al., 2015).

In the 2000s, Jiri Mlikovsky examined records of the Slender-Billed Curlew in Central Europe. Many of these records have incomplete or contradicting information that made them doubtful. After investigating a Whimbrel collected in southeast Poland in 1915, Mlikovsky was pleasantly surprised that this specimen was actually one of the only authentic Slender-Billed Curlew specimens in Central Europe. Other specimens (such as one in Montenegro) turned out to be of other species. Specimens throughout Central Europe were often mislabeled and misidentified. This makes it harder for taxonomists and ornithologists to find out more about the Slender-Billed Curlew (Mlikovsky, 2004).

The lack of credible sightings before and after 1995 makes it hard for conservationists to continue looking for the Slender-Billed Curlew and makes the case easier for doubters that insist that the bird is extinct.

Perhaps the most controversial sighting of the Slender-Billed Curlew was the one at Druridge Bay, Northumberland in the United Kingdom from May 4-7, 1998. A strange curlew was spotted amongst a flock of Eurasian Curlews. A photo was taken of the “Druridge Bay Curlew” that was later shown to reviewers. At first, the sighting was accepted as a Slender-Billed Curlew and added to the British List in 2003. It was the first time this bird had been seen in the country. However, shortly after the sighting was accepted, many complained that those behind the decision were rushed into it or pressured by conservationists. They also were not convinced that the bird in the photo was a Slender-Billed Curlew. In 2014, the sighting was questioned and removed from the British List after a contentious majority vote. According to those that voted against the record, they felt that the evidence for this being a Slender-Billed Curlew was not convincing enough. They based their decision based on factors such as:

1. The fact that small Eurasian Curlews like the one in the photo were seen in Britain in 2004. These Eurasian Curlews not only looked like the Druridge Bay Curlew but also have a broad bill base and chevron patterns on the flank feathers.

2. After a three-year review of the sighting with new video evidence not before shown to reviewers, many were not convinced with the video’s quality or with how the bird was seen. Many were not able to accurately judge the bird’s physical traits based on the poor quality. These videos were compared with known videos of the Slender-Billed Curlew in Morocco. This comparison only shed more doubt on the Druridge Bay Curlew’s identity.

3. The pattern on the underside of the outer primaries that did not have the plain, grey-brown undersides in the outer primaries typical of Slender-Billed Curlews.

4. The tibia feathering was not long enough.

5. The length of the primary projection in relation to the tail was not long enough with the primary tips falling level with or beyond the tail tip.

6. The leg color was not dark enough.

7. The indistinct eye ring and overall jizz was not enough.

8. Four to five primaries of the Druridge Bay Curlew did not have the uniform and dark merging to black at the primary tips to create the characteristic dark wedge of the species.

9. The bird in the photo was not tiny enough.

10. There was disagreement over whether the bill was small enough to be a Slender-Billed Curlew. Many thought the bill matched that of the species with a slender, short, and black bill with a restricted pale base to the lower mandible and no broader bill tip. Others were not sure.

11. Even though the Druridge Bay Curlew had the black heart or diamond shaped spotting on the flanks on a white background as well as a combination of diamond-shaped spots with individual barred feathers, there was doubt since many Eurasian Curlews have similar patterns.

12. The upperparts of the Druridge Bay Curlew are contrasting similar to a Eurasian Curlew.

13. The upperwing of the bird showed a combination of very dark primaries and pale inner primaries and secondaries forming a pale trailing wedge in the wing like a Slender-Billed Curlew. Nonetheless, critics pointed out that this can also be seen in some Eurasian Curlews.

14. The Druridge Bay Curlew had the thinner brown/black tail barring on a uniform white background in terms of tail pattern and color like a Slender-Billed Curlew. This was not able to convince enough reviewers since it could not be completely ruled out that this could not occur in Eurasian Curlews.

15. The bird had a weaker eye ring than those seen on Slender-Billed Curlews.

Millions of birdwatchers across the world (especially in Britain) were disappointed with the decision to reject the sighting. They believed the Druridge Bay Curlew showed many of the traits of a Slender-Billed Curlew such as the well-marked supercilium, darker lores, the capped appearance with a thin median crown-stripe, the sharp demarcation between the streaked, buffish upper breast and black-streaked lower breast and spotted flanks that form a pectoral band, and the white axillaries and underwing coverts. If the sighting stood, this would mean that the bird at Druridge Bay was a first summer Slender-Billed Curlew. This meant that at least one pair of this species bred somewhere and that there must be an undiscovered breeding ground somewhere. Rejecting this sighting vindicates what doubters and pessimists have been saying since 1995 in that the last Slender-Billed Curlew at Merja Zerga in Morocco was the last of the species. The verdict came up for another vote in June 2013 but remained unchanged.

The evidence surrounding the identity of the Druridge Bay Curlew had too much doubt for a unanimous vote needed to confirm the bird’s identity as a Slender-Billed Curlew. There was no clear pattern based on those who voted “yes” or “no.” The sighting’s rejection does not mean that the Druridge Bay Curlew was not a Slender-Billed Curlew. It could have been one or perhaps a hybrid. It just means that the evidence presented was not enough to confirm the bird’s identity. The main lesson here is how difficult it is to tell the difference between the Slender-Billed Curlew and her close relative, the Eurasian Curlew (Collinson et al., 2014).

Taxonomy

As a member of the genus Numenius, the Slender-billed Curlew is most closely related to other curlew species and Whimbrels. In 2019, a team of scientists tested a Slender-Billed Curlew specimen collected in 1855 in the Crimea that was housed at the Zoological Museum of Lomonosov at Moscow State University. From this specimen, they created the first DNA sequence-based species-level phylogeny for the Slender-billed Curlew confirming that it is a distinct species that is closely related to Eurasian Curlew (Sharko et al., 2019).

Page Editors

- Search for Lost Birds

- Nick Ortiz

Species News

Lost forever: The Slender-billed Curlew is extinct

John C. Mittermeier / 26 Nov 2024

Read MoreThere have recently been some incredible stories of lost birds being rediscovered. The Black-naped Pheasant-pigeon was photographed after 126 years, the Santa Marta Sabrewing was found after 76 years, the New Britain Goshawk was documented for the first time in 55 years, to name a few. Sadly though, not all lost birds can be rediscovered.

This reality is highlighted by the recent publication of a study led by scientists at the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds, BirdLife International, Naturalis, and Natural History Museum London concluding that the Slender-billed Curlew (Numenius tenuirostris) is extinct. Previously considered critically endangered, this elegant shorebird once bred in central Asia and south Siberia and wintered in wetlands around the Mediterranean basin and Arabian Peninsula. Migrating Slender-billed Curlews passed through central and eastern Europe turning up at locations in Hungary, Italy, Germany, and the Netherlands, among others.*

Last documented in 1995, the curlew was a lost bird that had been missing for 29 years.

As the study authors describe, it is difficult to pinpoint a single variable that precipitated the curlew’s decline. More than likely, it was a combination of factors. Agricultural expansion reduced habitat on the breeding grounds and in migratory stopover sites. Wetlands on the wintering grounds were drained and depleted. Migrating birds were shot by hunters. Like other curlew species, Slender-billeds were long-lived and slow to reproduce making it hard for their populations to recover.

If this all sounds familiar, it is because it is. Nearly all North American shorebird species are declining. More than half of them have lost over 50% of their population in the past 40 years. Globally, widespread species like Dunlins (Caldris alpina) and Black-bellied Plovers (Pluvialis squatarola) are now considered threatened or nearly so. Four of the seven remaining curlew species are threatened or near threatened. The Eskimo Curlew (Numenius borealis), the western hemisphere’s version of the Slender-billed, is ‘critically endangered (possibly extinct)’ (last documented in Barbados in 1963, the Eskimo Curlew remains a lost bird for now, but the prospects of a rediscovery seem vanishingly slim). Across the board, varying combinations of those same factors that impacted the Slender-billed – habitat loss, disturbance, hunting – are likely to blame for these drops in shorebird populations.

Whatever the specific cause of the Slender-billed Curlew’s disappearance, its numbers were dropping noticeably by the start of the twentieth century. A 1912 report noted that the species was declining and, by the 1940s, the population was low enough that there were concerns that it could go extinct. In 1988, it was listed as threatened. In 1995, the last documented individuals were photographed in the Merja Zerga wetlands along the Atlantic coast of Morocco. A year later, in 1996, a conservation action plan for the curlew was developed. Too little, too late.

Sometimes extinct species can seem like they belong to a distant past where they inhabited environments that no longer exist. But part of what stands out about the curlew’s story is how recent it feels. There are color photographs and even videos of Slender-billed Curlews. The birds were seen at locations that are still regularly visited, like Merja Zerga, and some of those places probably do not look much different now from how they did thirty or forty years ago when the last curlews were there. Many people birding today saw Slender-billed Curlews. Many others probably imagined it as a bird they could potentially see.

What can conservationists take away from this news about the curlew? For one, it is a depressing reminder that birds everywhere are at risk. The Slender-billed Curlew is the first recorded extinction of a bird species from mainland Europe, a region not known for its avian extinctions. As Alex Berryman, Red List Officer at BirdLife International, and a co-author of the study points out: “The rate of continental extinctions is increasing, and urgent conservation action is desperately needed to save birds. Without it, we must be braced for a much larger extinction wave washing over continents.” Not good news. On continents, grassland birds and migratory shorebirds, both categories relevant to the curlew, are among those most at risk.

Second, the curlew reminds us that conservation needs to be proactive. As the authors point out, the best chance to implement a conservation plan for the curlew, if there was one, was when those first calls for action were made in 1940s, rather than in 1996, one year after what would turn out to be the last documented record. Are there species starting to decline now that in fifty years we will wish we took more action on? The dramatic drops in the populations of multiple shorebird species certainly suggests there could be. If anything, this news about the Slender-billed Curlew emphasizes that these declines need to be taken seriously and that measures to help improve populations need to start sooner rather than later.

From a Search for Lost Birds perspective, this paper is also an important case study in the value of determining whether a lost species is extinct. Trying to find lost birds is difficult, but proving that one is not there can be even harder, especially for wide-ranging species like the Slender-billed Curlew. How can we be certain there isn’t a flock of curlews breeding in an isolated region of southern Siberia and passing undetected along a migration route where there are no birdwatchers to notice them? In reality, it is impossible to be absolutely certain. Instead, we need to make the best possible estimate with the given data, something this new study accomplishes by modeling a combination of threats, survey effort and the distribution of records over time. This is complicated and works better in areas with lots of data, like continental Europe. Determining extinction will be harder but no less important to do for some of the lost birds in areas with fewer observers and harder to measure threats. This is grim work. Settling on the conclusion that a species is extinct can feel like it goes against our feelings of optimism and hope. Fail to acknowledge that some birds are gone, however, and we run the risk of spending resources on species that are no longer there and missing the true scale of the extinction crisis.

It is hard to find a silver lining in news like this, but if there is one maybe it is that sometimes bad news can help trigger actions. The catastrophic declines of herons and egrets for the plume trade in the early twentieth century prompted conservation legislation and the creation of new conservation organizations in Europe and North America. Public response to disappearing populations of raptors and songbirds helped lead to legislation outlawing the use of DDT. Maybe, the Slender-billed Curlew can also help inspire conservation actions. For the 120 lost birds now remaining on the lost birds list it feels more urgent than ever to try to find them while we still can.

*An exceptional record of a Slender-billed Curlew from Ontario, Canada, in 1925, though intriguing, seems to be questionable.

The paper “Global extinction of the Slender-billed Curlew (Numenius tenuirostrsis)” by G. M. Buchanan, B. Chapple, A. J. Berryman, N. Crockford, J. F. F. J. Jansen, and A. L. Bond is published in the journal Ibis and is available open access online.

For information on steps you can help take to prevent declines in shorebirds and other species see American Bird Conservancy’s 3 billion birds page: https://abcbirds.org/3-billion-birds/

More details on the Slender-billed Curlew are available on its Birds of the World profile.

Support The Search for Lost Birds

Donations from supporters like you make expeditions, science, and conservation possible. Help support the Search.