Vilcabamba Inca

Coeligena eisenmanniFAMILY

Hummingbirds (Trochilidae)

LAST DOCUMENTED

1967

(59 years)

REGION

South America

IUCN STATUS

Least Concern

Background

This large and beautiful hummingbird is restricted to the Vilcabamba mountains of south-central Peru. The inca was described in 1985 based on specimens that had been collected nearly twenty-years earlier in 1967. Despite a number of observations, the species was not documented until August 2024 when the first photographs and videos were taken by Carole Turek as part of her quest to see all the hummingbird species in the world.

The taxonomic status of Vilcabamba Inca is debated. The inca was initially described as a subspecies of the widespread Collared Inca (Coeligena torquata). It continues to be treated as a subspecies by the Clements global taxonomy and South American Checklist Committee, while the HBW/BirdLife global taxonomy recognizes it, along with several other subspecies of Collared Inca, as a distinct species. In addition to its unique geographic distribution, the Vilcabamba Inca differs from other subspecies of Collared Inca by having coppery uppertail coverts.

The Vilcabamba Inca inhabits cloud forest between 1,600-3,000 m (IUCN Red List).

This species was described by Dr. J. Weske in 1985 as a new subspecies of Collared Inca. According to him, this bird was found in mid-elevation forest in the northern Cordillera Vilcabamba which is located in the front range of the Andes in south-central Peru. The lowlands of the Rio Apurimac valley creates a barrier between the Vilcabamba Inca and her relatives to the west and northwest of the country. He remarks that the bird's plumage pattern and range coincides with the northern, white-banded subspecies group of the Collared Inca and the southern, rufous-banded group (Weske, 1985). It is interesting to note that Weske does not actually list the Vilcabamba Inca as a separate species but as a subspecies of the Collared Inca. This seems to be the consensus among many ornithologists.

Conservation Status

This species is classified as Least Concern by the IUCN which made its last assessment in 2016. Despite its small range, the Vilcabamba Inca is classified as such because there is not enough data according to the IUCN's criteria to classify this bird as Vulnerable or Endangered. Even though the population size of this species is unknown, it is thought to be decreasing due to the loss of the cloud forests that it inhabits in Peru (IUCN Red List).

For a distribution map of the Vilcabamba Inca, click here.

Last Documented

A Vilcabamba Inca was videoed and photographed by Carole Turek in August 2024. These appear to be the first-ever photographs and video of the species alive. Prior to this, the documented record we are aware of are the types specimens that were collected in July 1967 (July 1967; AMNH 820476). It is worth noting that there were a number of sightings of the inca in the intervening years (e.g., in eBird).

Research Priorities

A DNA analysis of museum specimens may help settle the debate among taxonomists about whether or not the Vilcabamba Inca is a subspecies of the Collared Inca or a separate species.

Taxonomy

There is disagreement among taxonomists regarding whether to treat the Vilcabamba Inca as a distinct species or as a subspecies of Collared Inca (Coeligena torquata).

Depending on the organization, the Collared Inca has several subspecies. According to the International Ornithological Committee (IOC) and the Clements Taxonomy, there are five species of Collared Inca: Coeligena torquata torquata, coeligena torquata fulgidigula, coeligena torquata margaretae, coeligena torquata insectivora, and coeligena torquata eisenmanni (Vilcabamba Inca). The South American Classification Committee of the American Ornithological Society (SACC) adds three other subspecies: coeligena torquata conradii, coeligena torquata omissa, and coeligena torquata inca. The IOC and Clements treat the first as the Green Inca and the other two as the Gould's Inca. It seems to be primarily Birdlife International's Handbook of the Birds of the World that sees the Vilcabamba Inca as a separate species and that the consensus is that this bird is a subspecies of the Collared Inca (Birds of the World).

Page Editors

- Search for Lost Birds

- Nick Ortiz

Species News

FOUND: How the Vilcabamba Inca Was Documented for the First Time in 57 Years

John C. Mittermeier / 31 Mar 2025

Read MoreWhile looking for one lost bird, Carole Turek learned of another. She had traveled to Colombia’s Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta mountains in spring 2024, hoping to photograph the elusive Santa Marta Sabrewing (Campylopterus phainopeplus). The critically endangered species was lost to science until its rediscovery in 2022. With the help of American Bird Conservancy’s (ABC’s) local partners, Turek was delighted to find and film the rare sabrewing — one step closer to her goal of photographing every hummingbird species in the world.

John Mittermeier, director of the Search for Lost Birds at ABC, and Dan Lebbin, ABC’s Vice President of Threatened Species, were part of the team that joined Turek on the trip. Upon discovering her ambitious quest, they asked if she had heard of the Vilcabamba Inca (Coeligena eisenmanni). The bird was first described by Dr. John Weske in 1985 based on specimens collected in 1967. Restricted to the Vilcabamba mountains of south-central Peru, the lost species had not been documented for 57 years.

Turek was up for the challenge. With plans to visit Peru later that summer with William Orellana, a birding guide and photographer who accompanies Turek on every expedition, she added four days in the Vilcabamba region to the itinerary. In August 2024, they captured the first-ever photographs and video of the Vilcabamba Inca in the wild.

A Lucky Morning in the Mountains

On the first of four days in the Vilcabamba district, Turek and Orellana, together with guides Baldomero Vazquez of Turismo Nor Perú and Marcelo Quipo, left their lodge in Pucyura long before sunrise. They ventured into the mountains, where the Vilcabamba Inca inhabits cloud forest between 1600 and 3000 meters of elevation. Turek chose a specific destination based on where eBird users had previously spotted the lost hummingbird. Their reports included GPS coordinates but lacked photos, videos, or audio recordings of the species.

After several hours of driving up rough mountain roads, the team arrived at the site. They set up cameras in front of tubular orange flowers and, expecting a long wait, sat down for some breakfast. Everyone had just started to eat when Quipo looked up and said, “I think that’s the bird!”

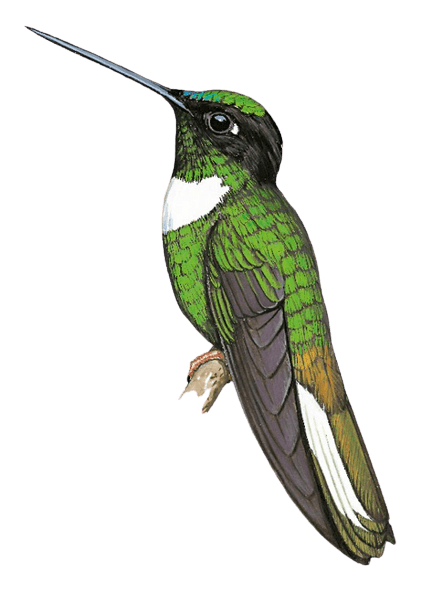

There it was, drinking from the nectar-filled flowers: a large, straight-billed hummingbird with a dark green body, black head, white pectoral band, mostly white tail, and coppery upper tail coverts.

“I heard a hummingbird, and I was sure it was a Vilcabamba Inca because I had never heard any sound like it,” Quipo recalls. “It was a moment of joy. I couldn’t believe it. I knew how important it was to find this species that was missing for years.”

“We dropped everything and ran for the cameras,” Turek remembers. “William got a four-second video, I got about 15-20 pictures, and that was it. The bird flew away.”

The team waited all day to see if the hummingbird would return. They revisited the site the following morning, and the next, hoping to take more photographs. But the bird didn’t show.

“We were stunned that we found it so fast. We were so excited, but not as excited as we should have been,” Turek says. The group didn’t realize that their first glimpse of the Vilcabamba Inca would also be their last. “Maybe we frightened it by jumping up and taking pictures,” she adds.

Although Turek spent less time with the Vilcabamba Inca than she had hoped, she still managed to capture definitive proof of the bird’s existence. After almost 60 years, the lost hummingbird species had been found.

Turek shared a video of the expedition with more than 125,000 subscribers on her YouTube channel, Hummingbird Spot. Using visual media to highlight lost and lesser-known birds is a valuable tool for connecting new audiences with species in need of attention.

“Most people won’t have the chance to visit the Vilcabamba area,” says Dustin Chen, a wildlife photographer focused on endemic birds in remote parts of the world. “Good-quality photos present the beauty of those birds and make us feel that they are valuable and should be protected. Awareness is always the center of conservation work.”

Looking Forward

The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species classified the Vilcabamba Inca as Least Concern in 2016. According to the IUCN's criteria, there were not enough data to deem the species Vulnerable or Endangered. The population size of the Vilcabamba Inca is unknown; however, given the ongoing destruction, degradation, and fragmentation of Andean cloud forests, experts suspect that the species is in decline. The Vilcabamba mountains have faced fewer ecological disturbances than other bird habitats in Peru, but mining and agricultural development are slowly encroaching on the area.

Hopefully, the 2024 observation of the Vilcabamba Inca will encourage birders to look for and document the species and help provide researchers the necessary data to quantify its population size and trends. Further research could also settle the debate between taxonomists as to whether the bird is a distinct species. Many taxonomies maintain Weske’s 1985 classification of the hummingbird as a subspecies of the widespread Collared Inca (Coeligena torquata). Others recognize the Vilcabamba Inca as a separate species on account of its unique geographic distribution and coppery upper tail coverts. DNA analyses of museum specimens and surveys of the bird in the wild may resolve these disagreements.

Rediscoveries of lost and elusive species like the Vilcabamba Inca, coupled with subsequent research, expand our understanding of bird diversity in ecosystems across the globe. New observations inform the work of local conservationists and build additional support for their efforts.

“Documenting the continued survival of lost birds, as Carole Turek and William Orellana have done with the Vilcabamba Inca, is an important contribution to our understanding of these species — and can set in motion action to protect these species and others that co-occur in the same habitats” says Lebbin.

“It increases interest in the area that we want to protect, and gives us visibility around the world,” says Constantino Aucca Chutas, president of Asociación Ecosistemas Andinos (ECOAN), an ABC partner. Far to the north of the Vilcabamba Inca’s habitat, ECOAN worked with ABC to establish the Abra Patricia Reserve in 2005. The reserve now protects more than 25,000 acres of the Andes, including the habitat of the critically endangered, once-lost Long-whiskered Owlet. Aucca continues, “We have the passion, we have the people, and we have the spirit to continue doing more and more to protect birds in Peru.”

Nina Foster is a science communication specialist with interests in ornithology, forest ecology, and sustainable agriculture. She holds a BA in English literature with a minor in integrative biology from Harvard University and is currently the Post-baccalaureate Fellow in Plant Humanities at Dumbarton Oaks.

Support The Search for Lost Birds

Donations from supporters like you make expeditions, science, and conservation possible. Help support the Search.