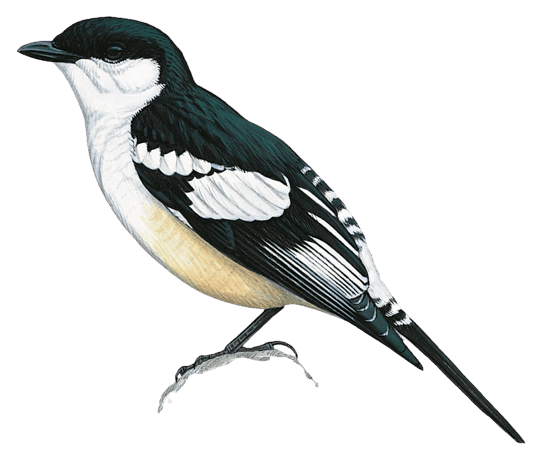

Mussau Triller

Lalage conjunctaFAMILY

Cuckooshrikes (Campephagidae)

LAST DOCUMENTED

1979

(46 years)

REGION

Oceania

IUCN STATUS

Vulnerable

Species News

FOUND: Birders rediscover lost bird on Mussau in Papua New Guinea!

John C. Mittermeier / 26 Aug 2024

Read MoreIn June 2024, Joshua Bergmark led a group of birders through the forests of Mussau Island, the largest of the St. Matthias islands off the northeast coast of Papua New Guinea in the Bismarck Archipelago. It had been a successful trip so far, and the group reached Mussau 10 days into the 16 day trip. They had spotted three of the island’s four endemic species—the Mussau Monarch, Mussau Fantail and the Mussau Flycatcher—and were now searching for the elusive Mussau Triller.

The triller, a member of the cuckooshrike family, was last documented on Mussau in 1979, and is listed as a lost bird by the Search for Lost Birds, a collaboration between American Bird Conservatory (ABC), Re:wild and BirdLife International. Trillers, which are found across Australasia and Asia, are typically gray, white and black—Mussau Trillers have a distinct chestnut colouring on their breasts—and eat fruit and insects. Like the monarch, fantail and flycatcher, Mussau Trillers are forest birds, but prefer the taller trees in the dense forest at the center of the island, which can make them harder to find.

Bergmark, who is from Sydney, Australia, and co-founder of Ornis Birding Expeditions, secured an old ambulance for the birding group to drive farther into the forest center. After driving for an hour, the group got out and walked, but at the base of a steep hill, some stopped and waited to be driven up, while others began the ascent on foot. That turned out to be a fortuitous choice.

A birder who chose to wait noticed a couple of birds quietly perched in a nearby tree. Lo and behold, he had spotted the Mussau Triller. The other members of the group returned soon afterwards and together they took the first known photographs and sound recordings of the bird. They documented nine birds across three flocks.

“Usually, you often hear these birds before you see them. In this case one of the clients saw it first before he heard anything,” says Bergmark. “They were just moving around with the other birds and feeding, doing their own thing while we watched them.”

Logging a possible threat

The Mussau Triller is assessed as Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species because of logging on the island since the 1980s. According to Global Forest Watch, primary forest in New Ireland province, which includes Mussau, decreased 7.2% between 2000 and 2023.

On his last visit to Mussau six years ago, Bergmark took the first known photographs of the Mussau Flycatcher. At the time, he couldn’t search for the triller because the island’s interior forests were inaccessible. This past June, he noted, it was likely that his birding group were able to spot the triller because logging roads now cut through the forest, even at the island’s summit, 1,600 feet (500 meters) above sea level.

“Looking at satellite images of forest cover, we can have a tendency to assume that species like the triller are doing fine despite the lack of recent records,” says John Mittermeier, director of the Search for Lost Birds for ABC. “But in fact it is vitally important to check up on island species, like the triller. We don’t know how a bird like this responds to these habitat changes caused by logging and invasive species. The fact that Josh and his group found the triller and confirmed its presence after so many years is stunning news.”

Mittermeier emphasized that other island birds in the area have not fared so well, and the vast majority of all bird extinctions have happened on islands, like Mussau. He pointed to how the Makira Moorhen of the Solomon Islands was last documented in 1929 and for many years was assumed to be secure—despite the lack of further records—because of the amount of forest on the island where it lived. In fact, he said, the species was probably declining rapidly and multiple recent searches have failed to find it at all.

“The moorhen is always in my mind when I think about the importance of checking up on island birds,” he says. “It should be a red flag if no one has documented a species in more than 10 years.”

Birding community a valuable resource for conservation

Bergmark is co-founder of Ornis Birding Expeditions, which specializes in birding tours in remote regions around the world. The East Melanesian Islands are a biodiversity hotspot and, following the rediscovery of the triller, are home to 15 lost birds, making the area one of the three highest priority regions in the world for lost birds, along with mainland New Guinea and the Democratic Republic of Congo. The Islands also have one of the highest rates of species endemism in the world.

“That’s my favourite area in the world for birding by far,” says Bergmark. “It's one of the few regions where there's still very little known about a lot of the birds and the other animals: how to find them, where they are, how they live. Almost every time I go back to New Guinea, if I'm doing a tour, we find something interesting. Something that hasn't necessarily been documented before.”

The rediscovery and photographs of the Mussau Triller are an example of the valuable resource that the global birding community is for the Search for Lost Birds, said Mittermeier. After the Search for Lost Birds was launched in 2021, ABC reached out to Bergmark and other experts because of their experience searching for birds in places like Melanesia. According to a recent study published in Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, citizen science platforms like eBird, Xeno-canto and iNaturalist, where anyone can record their sightings and upload photographs of birds around the globe—Bergmark said his company regularly uploads findings to eBird—contain records on 98% of all bird species on earth.

“That documentation is a hugely valuable data point for us as conservationists,” says Mittermeier. “ One of the most basic pieces of information you need in conservation is simply knowing where a species is and geo-located records submitted by citizen scientists, like Josh’s photographs of the triller, help provide that understanding. That’s square one for any conservation analysis and planning.”

Bergmark says a bird touring company’s ability to reach remote areas is a good thing for conservationists. “As much as birdwatchers and researchers would like to just go and spend time looking at birds in these remote areas, it’s difficult to do it in formats other than organized tours like this.”

“For these lost birds, where ecological data is often so scant, each and every observation contributes disproportionately to our understanding of the threats facing them (if any), as well as their habitat needs and population trend,” said Alex Berryman, red list officer for BirdLife International.

On the June trip Bergmark also snapped his first photographs of the Manus Dwarf-Kingfisher, a bird endemic to Manus Island west of Mussau, that was also lost from 2002 until 2022. He also photographed the New Hanover Mannikin, an endemic species to New Hanover Island, south of Manus Island, which was close to being considered a lost bird.

“Every time we get out to one of these rarely visited islands or places, and just get on the ground, walk around and see things that few other people have seen, it’s exciting,” says Bergmark. “Yes, it's exciting, always.”

Support The Search for Lost Birds

Donations from supporters like you make expeditions, science, and conservation possible. Help support the Search.