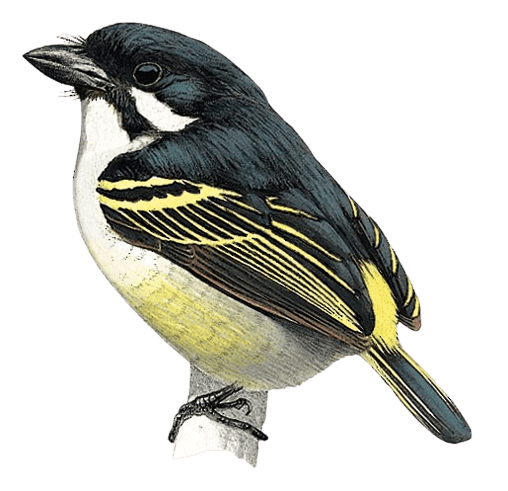

Yellow-rumped Tinkerbird (White-chested)

Pogoniulus bilineatus makawaiFAMILY

African Barbets (Lybiidae)

LAST DOCUMENTED

1964

(62 years)

REGION

Africa

IUCN STATUS

Not Evaluated

Background

The White-Chested Tinkerbird looks so similar to the Yellow-Rumped Tinkerbird and the subspecies bilineatus mfumbiri that is necessary to compare the physical traits of this species with its congeners in order to make identification in the field easier.

Description

Yellow-Rumped Tinkerbird (Pogoniulus bilineatus)

Black head with white stripes above and below the eye

White on the forehead

The rectrices are narrowly bordered with yellow on the outer webs

Yellow edges on secondaries and wing-coverts

Bases of feathers on mantle and underparts are dark (Collar and Fishpool, 2006)

Grey breast

Yellow rump

Greenish-black plumage

Yellowish underbelly

Short, robust bill

This species has several subspecies: Pogoniulus bilineatus leucolaimus, P.b poensis, P.b. mfumbiri, P.b jacksoni, and P.b fischeri

This bird can be found over an extensive range that spans many countries in Sub-Saharan Africa such as Angola and Zambia (IUCN Red List)

Prefers evergreen forests and dense shrub but it also seen in the locality where the sole White-Chested Tinkerbird specimen was located (Benson and Irwin, 1965)

Pogoniulus bilineatus mfumbiri

Forehead, crown, mantle, and wings are black with a greenish gloss

The lower chest, belly, and flanks have a greenish tinge

White supraorbital stripe

Yellow fringes on the secondaries and wing-coverts

Whitish chin

Throat and belly a pale, whitish grey with a slight greenish tinge

Lower breast and belly have a greenish tinge

Underside of the bend of the wing is white

Bases of feathers on mantle and underparts are dark

Bill is completely black

Rictal bristles

Pale feet, legs, toes, and claws

Has a lower facial stripe entirely enclosed with black

Has a narrow line of black that appears to isolate the lower white cheek stripe (Collar and Fishpool, 2006)

White-Chested Tinkerbird

Forehead, crown, mantle, and wings are black with a greenish gloss

Forehead lacks any white

White breast and moustache strip

Pale cream white line that extends from gape to behind the black ear-coverts and joins with the pale underparts from which it is separated by a black patch

The rump is a lemon yellow

The rectrices are narrowly bordered with yellow on the outer webs

Yellow edges on secondaries and wing-coverts are paler and narrower

Black chin that complements the black patch surrounded by white at the center of the breast

Throat and upper chest are a creamy white with faint black shadow bars that fade into yellow on the lower chest

The lower chest, belly, and flanks are a pale lemon yellow

Pale blackish barring below the chest on the underparts

Dark brown eye (Benson and Irwin, 1965)

No white supraorbital stripe

White line below the ear-coverts that starts at the gape and does not go below the eye in a continuous band from over the bill

Yellow fringes on the secondaries and wing-coverts are paler and narrower

Greyish black chin that is flecked in the center with white

Creamy white throat and upper breast that fades to pale yellow on the lower chest

No greenish tinge on lower breast and belly

Central abdomen is black

Pale blackish shadow barring throughout the underparts below breast that extends to the creamy-white throat (barely perceptible)

Underside of the bend of the wing is black

Tibial feathering is a suffused black

Bases of feathers on mantle and underparts are pale

Bill is broader and heavier than other members of the bilineatus species as well as more arched and less conical with cutting edges of the upper mandible flared around the gape

Black bill with a whitish base that extends to the nostrils to halfway along the cutting edges

Rictal bristles

Paler feet, legs, toes, and claws

Legs more robust than other members of the bilineatus species

Has a lower facial stripe entirely enclosed by black

Has a narrow line of black that appears to isolate the white cheek stripe

Has a have starker color pattern than the Yellow-Rumped Tinkerbird and the Yellow-Throated Tinkerbird (Pogoniulus subsulphureus)

Wing is 56 mm

Tail is 32 mm

Tarsus is 15 mm (Collar and Fishpool, 2006)

Habitat

The only known specimen of the White-Chested Tinkerbird was found in a Cryptosepalum thicket in northwest Zambia with the main species being Cryptosepalum pseudotaxus

This habitat is known to also exist in areas of Zambia and Angola

Two of these areas are West Lunga National Park and the Lukwakwa Game Management Area (both in Zambia) where the Cryptosepalum thickets are sparsely populated and very difficult to clear for agriculture (Butchart, 2007)

The White-Chested Tinkerbird and the Yellow-Rumped Tinkerbird inhabit similar habitats

Other Information

Vocal behavior unknown

This species is believed to be an insectivore like its congeners

The bird’s large bill suggests the species is a specialist in eating berries from mistletoes

Life span 8.5 years (IUCN Red List)

Conservation Status

There is not enough data on the White-Chested Tinkerbird to make an accurate assessment regarding the species’ conservation status. What can be said is that the Cryptosepalum forests and thickets where the lone specimen was found are hard to clear and not in danger of being destroyed. One can infer that the bird is safe for now based on this observation. This species extent of occurrence is 4,100 km2 at an altitude of 1,130 m (IUCN Red List).

For a distribution map of the locality where the lone specimen of the White-Chested Tinkerbird was found, click here.

Last Documented

The only evidence of this enigmatic barbet is a single specimen collected in September 1964 from northwestern Zambia (Collar and Fishpool 2006). A genetic analysis of this specimen, however, indicates that it is probably best treated as a subspecies or aberrant form of the widespread Yellow-rumped Tinkerbird (P. bilineatus; Kirschel et al. 2018).

The only male specimen of the White-Chested Tinkerbird was found high in the canopy of a Cryptosepalum forest in Kalahari on September 6, 1964 by M.P Stuart Irvin and Jali Makawa. They claimed the specimen belong to an undescribed species of tinkerbird. They later sent the specimen to the British Natural History Museum (Benson and Irwin, 1965). The locality where it was found was called Mayau by Irwin and Makawa. It must be said that Mayau is not an actual place but, instead, refers either to a river or plain in the area (usually by the local name Mayowo). In this case, the locality was four miles north of Mayowo in the Kabompo District in northwest Zambia. The exact location within Mayowo where the specimen was found was 6 km north from where the track from Mwinilunga to Kabompo crosses the Mayowo River at an altitude of 1,150 m (Collar and Fishpool, 2006).

Despite sixty years of searching, the White-Chested Tinkerbird has not been seen nor heard, leading many to believe that the bird was not a real species at all.

Challenges & Concerns

Ever since this bird was discovered in 1964, there has been a huge debate surrounding the White-Chested Tinkerbird’s status as a distinct species.

All that is known about the White-Chested Tinkerbird is from a lone male specimen. This specimen was first described by C.W Benson and M.P.S Irwin (1965) who argued that the specimen was a different species due its distinct structure and color pattern (especially the black chin, shadow barring on the throat and belly, and the black patch on the abdomen) that separated it from the genus represented by the Yellow-Rumped Tinkerbird. They named the species Pogoniulus makawai after the African collector (Jali Makawa) who helped find the specimen. They were curious how this species was found in the same area as the Yellow-Rumped and the Yellow-Fronted (Pogoniulus chrysoconus) Tinkerbirds with the former preferring evergreen forest and dense shrub and the latter savannah woodland. They hypothesized that the fierce competition between the three forced the White-Chested Tinkerbird to adopt a “functional modification” that allowed her to change her feeding habits. This is reflected in the heavy bill that they argue was a result of adaptive differentiation; a phenomenon that is not uncommon among barbets of the Pogoniulus genus.

As soon as Benson and Irwin published their article, it immediately came under attack by other ornithologists who doubted the validity of the new species. The first to do this was Dr. Derek Goodwin (1965). He tentatively agreed with Benson and Irwin that the White-Chested Tinkerbird was a distinct species. Nonetheless, this was because he did not have enough evidence to prove them wrong. It was he who first proposed the idea that the specimen could be an aberrant individual. This argument would be used by future ornithologists to disprove the White-Chested Tinkerbird’s species status. He notes that a drop in melanin suffision can explain the white and yellowish-white feathers on the breast, belly, back, and mantle feathers on the specimen but it cannot explain the shadow bars. Apparently, the bird had enough melanin for that. Aberrant individuals can have more melanin in some areas than in others. While it is possible that the specimen is an aberrant individual of Yellow-Rumped Tinkerbird, Goodwin himself admitted that his melanism theory cannot account for all of the physical characteristics nor for the different color pattern of the specimen. Furthermore, he discounts the specimen’s species status based on the bill alone since other Yellow-Rumped Tinkerbirds have been known to have similarly heavy bills as that seen on the specimen. In fact, Goodwin found a specimen of Pogoniulus mfumbiri that matched the bill description of the specimen based on size and curvature. Nonetheless, Goodwin seems to contradict his own argument by mentioning that all specimens of mfumbiri that were collected in the Mayau locality where the sole specimen of the White-Chested Tinkerbird was found had slender, conical bills instead of the heavy bill found on the specimen. In the end, Goodwin was not able to refute the White-Chested Tinkerbird’s status as a new species but his ambivalent argument left more questions than answers. He set the stage for a long-running debate over this species’ validity that continues to this day.

In a landmark article published in 2006, N.J Collar and L.D.C Fishpool examined all of the literature surrounding the White-Chested Tinkerbird since 1964 and analyzed each case for and against this bird being a separate species. According to them, the evidence for this bird being a distinct species is scarce as most of it comes down to personal convictions and the unique physical characteristics of the only specimen found. The cases against this bird being a distinct species centered around the specimen being an aberrant individual or a subspecies, the specimen being found in an area undifferentiated by habitat or endemism, and the fact that no trace of the bird has been found after decades of intense surveys in the locality of its discovery. They argue that the White-Chested Tinkerbird’s unique characteristics rule out the specimen being an aberrant individual. Melanism seems unlikely since past cases of melanism in other species did not produce the lack of yellow and grey seen on the underparts nor the heavy bill of the specimen. They also rule out the argument that the characteristics were the result of a gene mutation since the differences produced from such an event would have produced melanized feathers instead of the simultaneous darkening and lightening seen in the specimen. Since the specimen was found in a habitat similar to the Yellow-Rumped Tinkerbird and Yellow-Fronted Tinkerbird (Pogoniulus chrysoconus), many ornithologists assumed that the two birds would compete with each other. Collar and Fishpool are skeptical of this argument since the heavy bill of the specimen suggests the White-Chested Tinkerbird would find a niche to avoid intense competition with her congeners. In terms of the intense surveys experts have claimed over the years, Collar and Fishpool question how intensive these searches actually were. The surveys conducted at the locality where the specimen was found along with names of those who participated are displayed below:

November 8-12, 1964 by M.P Stuart and Jali Makawa after they discovered the first and only specimen on September 6 the same year

May 2-8, 1965 by T.B Oatley

August 9-20, 1973 by R.J Dowsett and Jali Makawa where they collected 10 bilineatus specimens with none of them identified as the White-Chested Tinkerbird

April 14, 1974 by Bob Stjernstedt

1980 by Bowen

October 5-6, 1989 by Nigel Hunter

September 1-3, 1995 by Carl Beel

August 1996 by Pete Leonard

September 1998 by Paul van Daele

February and August 2000 and 2002 by Jorg Mellenthin

Dr. Françoise Dowsett-Lemaire and R.J Dowsett travelled several times to the locality as well as neighboring areas in the West Lunga National Park in Zambia in the 1970s, 80s, and 90s. While at first, they believed in the species’ validity, after their own searches proved fruitless, even they succumbed to the argument that the White-Chested Tinkerbird was probably an aberrant individual and not a distinct species at all.

What really made skeptics dismiss the validity of the White-Chested Tinkerbird as a species was the fact that this many surveys took place and no trace was found of the bird (not even any unusual calls). However, there is some hope according to Collar and Fishpool who argue that these surveys were not intensive enough and they took place in areas that are very inaccessible. Many who visited the area, like Carl Beel, noted that the Cryptosepalum forest is very dense, tangled, and difficult to move around in. He contends that there is still plenty of habitat yet to be explored with the dense thickets hiding all types of birds, including possibly the rare White-Chested Tinkerbird. While the main types of tinkerbirds seen in the area are the Yellow-Rumped and Yellow-Fronted Tinkerbirds, other tinkerbirds (such as the White-Chested Tinkerbird) may have moved on to other inaccessible habitats or are temporary residents in the area. Others, such as T.B Oatley, dispute Beel’s claims saying that the Cryptosepalum environment at the Mayau locality is not dense or tangled at all. It consists of open forest floor with scattered thickets. The area where the specimen was collected was a mosaic of miombo woodland and mavunda forest. In such an environment, Oatley argues that birds from the woodland can easily occupy the canopy of the forest patches in the area. He notes that the specimen was found in September, a time when birds, including altitudinal and Afrotropical migrants, in the region are known to move around in search of mates. Furthermore, the birds one finds in one part of the locality can change just by setting up camp a couple of miles away. If it’s true that all of these ornithologists and birdwatchers visited the Mayau locality in search of the White-Chested Tinkerbird, why do their arguments and observations differ so starkly?

After a detailed analysis, Collar and Fishpool conclude that there is not enough evidence to dismiss the White-Chested Tinkerbird as a distinct species. They are confident in their assertion that the species is rare throughout the Cryptosepalum forest in northwest Zambia and restricted to an uncommon habitat that borders this forest (such as a riverine forest). They theorize that the specimen was perhaps a straggler from Angola or the Democratic Republic of the Congo since the locality sits at the edge of the Yellow-Rumped Tinkerbird’s range in Central Africa. The White-Chested Tinkerbird may replace her congener in certain habitats. It’s also possible that the specimen could have been a hybrid with a member of the Yellow-Rumped Tinkerbird being one of the parents. In order to end this debate once and for all, Collar and Fishpool argue that an intensive, months-long survey needs to happen in the Mayau locality as well as in neighboring areas in the west and north. This survey should look for variations in the structure of the Crytosepalum forest caused by water or topographical features as well as activity within mistletoes (a favorite among several species of Tinkerbird). They contend that, outside of DNA analysis, this kind of survey may prove useful in confirming the White-Chested Tinkerbird’s status as a distinct species, "it is still too soon to place Pogoniulus makawai in synonymy with P. bilineatus, and if we look long and hard enough we may yet be pleasantly surprised" (Collar and Fishpool, 2006).

More than 50 years after the White-Chested Tinkerbird was first discovered, researchers led by Dr. Alexander Kirschel finally conducted a DNA analysis of the only White-Chested Tinkerbird specimen. To the chagrin of Fishpool and others who argued for the species’ validity, it appears that the doubters were right all along. According to the researchers, a DNA analysis proves that the White-Chested Tinkerbird is not a distinct species but either an aberrant individual like Goodwin suggested or a subspecies of the Yellow-Rumped Tinkerbird since the collected DNA implies that the bird is in the same clade along with other subspecies (such as Pogoniulus bilineatus jacksoni and P.b mfumbiri). They rule out the possibility that the specimen could be a hybrid with the mother being a Yellow-Rumped Tinkerbird (probably P.b mfumbiri) and the father possibly being a Yellow-Fronted Tinkerbird. But what about the strange color pattern of the specimen? They argue that a mutation of one or more genes associated with melanism combined with environmental factors were the main factors behind the strange color pattern. They conclude that the distance in pair sequences between certain genes suggest that the White-Chested Tinkerbird is a subspecies but not a species in its own right. Their study reminds one of a similar study where a DNA analysis of the only Liberian Greenbul (Phyllastrephus leucolepis) specimen revealed it to be a melanic morph of the Icterine Greenbul (Phyllastrephus icterinus). One thing that may give those holding out hope that the White-Chested Tinkerbird is a distinct species is the fact that the researchers did not include individuals of the Yellow-Rumped Tinkerbird population in northwest Zambia where the specimen was found. Further DNA analysis is needed to support their findings.

What does this mean for the future of the White-Chested Tinkerbird? Even though those that did the DNA analysis themselves admitted that more testing is needed (especially from individuals from the specimen locality), this is exactly the thing many ornithologists have been looking for to put the issue over the bird’s status to bed. With this study, many conservationists, who are already pressured with protecting millions of species during a mass extinction event caused by climate change and human activity, will be tempted to write off the White-Chested Tinkerbird as a subspecies of the Yellow-Rumped Tinkerbird and include the former in conservation strategies of the latter. Can anything be done to reverse this trend? Perhaps another DNA study or finding the White-Chested Tinkerbird will tell the tale.

Taxonomy

Order: Piciformes

Family: Lybiidae

Genus: Pogoniulus

Species: Pogoniulus makawai/Pogoniulus bilineatus makawai

The taxonomic status of the White-Chested Tinkerbird is in dispute with some believing the bird is a distinct species and other considering it a subspecies. The latter group point to a recent DNA analysis by Kirschel et al., (2018) of the lone specimen as justification for their argument. They argue that the bird is a subspecies of Yellow-Rumped Tinkerbird, an argument that is already supported by prominent ornithological institutions such as the Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

Page Editors

- Nick Ortiz

- Search for Lost Birds

Species News

- Nothing Yet.

Support The Search for Lost Birds

Donations from supporters like you make expeditions, science, and conservation possible. Help support the Search.