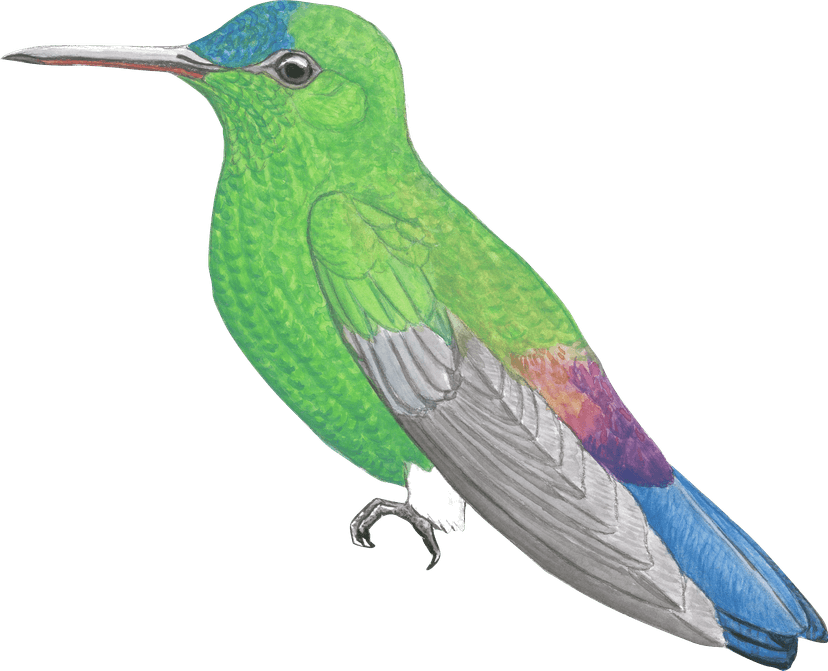

Guanacaste Hummingbird

Amazilia alfaroanaFAMILY

Hummingbirds (Trochilidae)

LAST DOCUMENTED

1895

(131 years)

REGION

North America

IUCN STATUS

Critically Endangered

Last Documented

This enigmatic hummingbird is known from only a single specimen, collected on Miravalles Volcano in northwestern Costa Rica (September 1895, contra the date in GBIF; Kirwan and Collar 2016).

Page Editors

- Search for Lost Birds

Species News

The search for Costa Rica’s most mysterious hummingbird

Cameron Rutt / 5 Jul 2023

Read MoreCosta Rica is a bustling and diverse hotspot for wildlife, where over 50 species of hummingbird have made their home. But one of these ‒ a little-known species lost to science for 125 years ‒ has spurred a new search among the tropical Costa Rican forests.

No one alive today has ever seen the mysterious Alfaro’s Hummingbird (also known as the Guanacaste Hummingbird), one of GWC’s most wanted lost birds and categorised by the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species as Critically Endangered. But a question mark still hangs over its current status. That’s because only one individual of the hummingbird has ever been collected ‒ in 1895, on the slopes of the Miravalles Volcano in northwest Costa Rica. And it’s also why an expedition to this region by GWC, in partnership with the American Bird Conservancy (ABC), is currently underway to probe the Alfaro’s Hummingbird’s possible whereabouts. If successfully found, it’ll help conservationists develop ways to protect the species from being lost forever.

A tricky candidate

The team setting out to search for the hummingbird is led by Ernesto Carman, a naturalist and bird guide from Costa Rica. Over the following year, each member of the four-person team will scout out the forests of the Miravalles Volcano, focusing their efforts on the southern slopes where the hummingbird was first collected. They’ll capture photos of any birds they can that match the description of the Alfaro’s species: a medium-sized hummingbird measuring about four inches with a green belly and throat, bluish-green back and dark tail. The team will look out for certain flowers that hummingbirds are attracted to for their nectar as a leading point and set up nets there to try and trap--and release--likely candidates. Because the information on the hummingbird’s location is so vague--found in just one unspecified spot on the volcano--the team will expand their search to other parts of Miravalles, as well as the surrounding volcanoes and national parks in the Guanacaste province.

But it won’t be easy to track it down. Not only does it remain to be seen whether it is still out there, the Alfaro’s Hummingbird also shares extremely similar features to other, more common hummingbird species in the region. One example is the Blue-vented Hummingbird found in both Costa Rica and neighbouring Nicaragua, which sports features identical to that of the Alfaro’s Hummingbird. The main difference is that the Alfaro’s species has a blue-tinted forehead.

“It may actually be very difficult to tell the species apart in the field just by looking at it or taking a photograph of it ‒ if the light’s not right, it’s going to look just like one of the similar species. So in the case of this hummingbird, it’ll be very important to be able to catch it and get a much closer look,” says Carman.

This striking resemblance has also meant that, ever since its discovery, there has been debate among ornithologists about how to classify the Alfaro’s Hummingbird. Is it a distinct species or was the individual from 1895 simply the hybrid offspring of two other hummingbird species? This has consequences for whether the hummingbird may be considered ‘lost’ in the first place.

“If you have a hybrid, it may have been something that occurred just once… That is still one of the most accepted possibilities that make people put it to one side and not even think about it,” Carman points out. “So there’s too little information to know right now [why it might be lost].”

A detailed analysis of the single existing specimen in 2016 suggested that the Alfaro’s Hummingbird should indeed be recognised as its own species. This can be put down to subtle differences between the specimen and similar-looking species, including the Indigo-capped Hummingbird of central Colombia. Compared to this species, for example, the Alfaro’s Hummingbird has a longer bill and tail, and slightly different feather colorings, such as a more continuously green chin to belly. This expedition marks an important advance in verifying this classification and, if it proves correct, determining whether the Alfaro’s Hummingbird has gone extinct or might still be dwelling in the Costa Rican forests.

Protecting lost species

If it is a distinct species, the hummingbird may have seemingly disappeared due to changes in its habitat, like many lost species before it. Though the area around the Miravalles Volcano has undergone habitat loss, its lower regions have recently started to regenerate, thanks to the maintenance of ‘buffer zones’ of undisturbed habitat for the geothermal power plants located at the volcano’s base. But Carman thinks that the Alfaro’s Hummingbird will probably be found higher up on the slopes. This is because the lower area of the volcano is a much larger, single and connected habitat, making it unlikely that the hummingbird would specifically evolve there and not occur elsewhere.

“If you’re looking for a species that’s quite particular and restricted, it’s going to be in a more specialized habitat that you would find higher up on the slopes, where you start getting this kind of island situation, which gives you different climate and weather and so on,” Carman says.

The Miravalles Volcano gained national park status in 2019, protecting the area from drastic habitat changes, but climate change remains an ever-pressing danger to the local wildlife. Shorter rainy seasons and longer dry spells will drive birds to higher elevations where it is cooler, but for those that have already made their home in the upper parts of the volcano ‒ like the Alfaro’s Hummingbird may have done ‒ there is nowhere else to go. If found, these effects could be the biggest threat to the hummingbird’s existence.

An effective conservation plan would depend on where the bird was spotted, Carman says. If it is found higher up on the volcano, for example, there would need to be urgent research into whether it exists in the same regions of neighboring volcanoes, such as the Tenorio Volcano, to specifically protect these areas. There’s also scope to expand conservation efforts to include other species that co-inhabit the region but haven’t been seen in many years.

“We are very hopeful that this search will rediscover a species that hasn't been recorded in over a century.” says Amy Upgren, ABC’s Director of Alliance for Zero Extinction and Key Diversity Areas Program. “But even if the hummingbird isn't found, the expedition should lead to improved knowledge of several other poorly understood birds.” As to why the team thinks the Alfaro’s Hummingbird could still be out there, the answer is simple. “Nobody has ever specifically looked for it,” says Carman. “Very few people have actually gone birdwatching up this volcano because there is no public access or official trails… It’s really limited how many people go there and nobody’s really aware of the possibility of the Alfaro’s Hummingbird existing anyway.”

“It would be quite phenomenal [to find it],” he adds.

Support The Search for Lost Birds

Donations from supporters like you make expeditions, science, and conservation possible. Help support the Search.